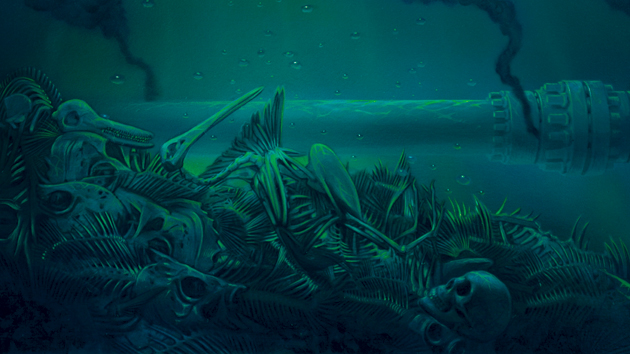

Illustration: Matt Mahurin

Read also: MoJo‘s complete BP coverage, Julia Whitty on the oil spill cover-up, and the rest of our special report on BP’s deep ocean secrets.

WHEN THE DEEPWATER Horizon rig exploded, BP was presented with a stark choice: Let the oil float to the surface, reach the shore, and allow the world to see the full scope of the damage; or hit as much of the oil as possible with toxic substances called dispersants to break it up into trillions of tiny droplets, keeping some of it from reaching the surface and making landfall—but also potentially killing more sea life than the oil might have destroyed by itself. The company chose the latter. By late July, it had applied a record 1.8 million gallons of dispersants, spraying them on the sea’s surface and injecting them directly at the well site, a technique never tried before.

Why, you might ask, was BP able to pump the Gulf full of chemicals that have never been tested for their human and environmental safety? The answer lies, in part, in the Toxic Substances Control Act, the 34-year-old law that governs the use of tens of thousands of hazardous chemicals. Under the act, companies don’t have to prove that substances they release into the air or water are safe—or in most cases even reveal what’s in their products.

In the case of dispersants, companies must ask the EPA for permission to use specific products—but the only basis for approval is whether those products are effective at breaking up oil. Companies are required to test the short-term toxicity of the dispersant and the oil-dispersant mixture on shrimp and fish, but those results have no bearing on approval, and there’s no requirement to assess the long-term impact. In fact, it’s the EPA that must prove an “unreasonable risk” if it wants companies to disclose what is in the dispersant—hard to do when the agency, you know, doesn’t know what’s in it.

BP’s chemical cocktails of choice were Corexit 9527A and 9500A, both made by Illinois-based Nalco. The manufacturer insists that the products are no more dangerous than common household cleaners such as dish soap—little consolation given that many of the chemicals in those cleaners haven’t been tested for safety, either. EPA administrator Lisa Jackson acknowledged that the impacts of using dispersants underwater and in large volume are largely unknown—”I’m amazed by how little science there is on the issue,” she told senators in May. Two days later, Jackson directed BP to switch to less-toxic dispersants, but BP said it hadn’t found the alternatives suitable and continued to use Corexit. The EPA also asked for the company’s study of alternatives; BP turned over a set of heavily redacted documents (PDF). Under pressure, Nalco eventually coughed up a list of Corexit ingredients—one of them is 2-butoxyethanol, a chemical that can cause liver and kidney damage and other health problems—but refused for some time to provide the exact formula; meanwhile, the EPA said it was barred from publishing its own studies on the ingredients because, according to a spokeswoman, that might be “confidential business information” that could lead to criminal prosecution.

The upshot: BP was allowed to keep dumping the chemicals. “We live in a world where we’re making tough decisions based on little science,” Jackson told reporters (PDF) on May 24. The EPA and the Coast Guard did ask BP to “scale back” use of Corexit, but as it turned out, the Coast Guard’s on-scene coordinator approved almost every single request from BP to use more dispersants.

In the end, says Richard Denison, senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, the problem with Corexit is bound up in the larger failure of chemical oversight: “We have a chemical policy that essentially has required very little testing and very little evidence of safety for pretty much all chemicals on the market, and that covers dispersants.” Legislation to reform the Toxic Substances Control Act—requiring mandatory ingredient disclosure and safety testing for some 84,000 chemicals whose risks have not been assessed anywhere—has been stalled in Congress for years. For now, the EPA has finally begun testing Corexit for toxicity. But that, notes Gina Solomon, senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, is “a little bit like closing the barn door after the horse is gone.”