Illustration (Map of CIA Rendition Flights): Trevor Paglen and John Emerson

The Washington Post, the Associated Press, and the Guardian reported Thursday on a court fight between two firms involved in the Central Intelligence Agency’s extraordinary rendition program. These sorts of billing disputes between CIA contractors happen occasionally, but they don’t normally make it far enough to reveal anything—usually, the government steps in and invokes the state secrets privilege and the case gets thrown out of court. But this time, someone messed up, and the case went forward, leading to the creation of hundreds of pages of almost entirely unredacted records that touch on many previously unrevealed aspects of the CIA program. (The international human rights group Reprieve first discovered the documents.)

The two firms involved in the court battle are Richmor Aviation, a New York-based company that operated charter planes, and Sportsflight Air, which served as a middleman between charter firms like Richmor and companies that needed planes—in this case, the government contracting giant DynCorp.

The plane that Richmor provided to SportsFlight, with the tail number N85VM, was just one of many used in the extraordinary rendition program. But N85VM, which was owned by Boston Red Sox co-owner Phillip Morse, was particularly notorious not only for being owned by Morse but also for being used in the case of Abu Omar, an Italian imam whose bungled 2005 rendition Peter Bergen covered for Mother Jones. (Afterward, the Italian judiciary sought to prosecute the CIA agents involved in the rendition. I interviewed Steve Hendricks, who wrote a book on the affair, last year.) The Post and the AP stories both note that the Richmor-Sportsflight records show N85VM traveling all over the world, with stops not just in Guantanamo Bay, but also in foreign countries famous for hosting secret CIA prisons or torturing prisoners on America’s behalf.

The Associated Press uncovered one particularly interesting tidbit in the court records. When Richmor flew to foreign countries under the Sportsflight-Dyncorp contract, its pilots and crew were provided with letters from a State Department official, Terry A. Hogan, that said the flights entailed “global support for U.S. embassies worldwide.” There’s just one problem: Hogan doesn’t appear to be a real person:

The AP could not locate Hogan. No official with that name is currently listed in State’s department-wide directory. A comprehensive 2004 State Department telephone directory contains no reference to Hogan, or variations of that name — despite records of four separate transit letters signed by Terry A. Hogan in January, March and April 2004. Several of the signatures on the diplomatic letters under Hogan’s name were noticeably different.

Lawrence Wilkerson, who was chief of staff for Secretary of State Colin Powell from 2001 to 2005 during the Bush administration, said he was not familiar with the Hogan letters and had not been aware of any direct State Department involvement in the CIA’s rendition program. Wilkerson said the multiple signatures would have raised questions about the documents’ authenticity.

This makes a lot of sense. The CIA is never especially eager to let other government agencies—especially the State Department—in on its most secret activities. So as ProPublica’s Eric Umansky (a Mother Jones alum) notes, it’s possible these documents were forged. (State declined to comment to ProPublica or the AP on the matter.)

There’s some (darkly) funny stuff in the court documents, which are mostly incredibly banal. (I obtained copies of them yesterday.) When Richmor’s president, Mahlon Richards, tells the judge, Paul Czaka, that Morse owned the plane used for the rendition flights, Czaka (presumably a Yankees fan) says, “I guess that concludes the case as far as you’re concerned. We can go home now—or I should say, get the heck out of my courtroom.”

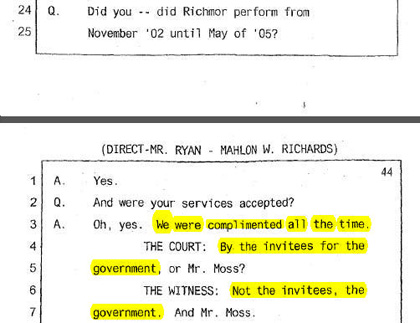

But my favorite bit of the trial comes when William Ryan, one of the attorneys for Richmor, is questioning Richards, the firm’s president. Throughout the case, all parties were fairly careful about describing exactly what Richmor was doing for SportsFlight (and for DynCorp, and ultimately for the government), referring to the passengers as “government personnel and their invitees.” This bit of the trial centers around whether Richmor’s ultimate client, the government, was happy with Richmor’s performance. Some confusion ensues:

No, I imagine the government’s “invitees” would not appreciate the service that Richmor was providing.

No, I imagine the government’s “invitees” would not appreciate the service that Richmor was providing.