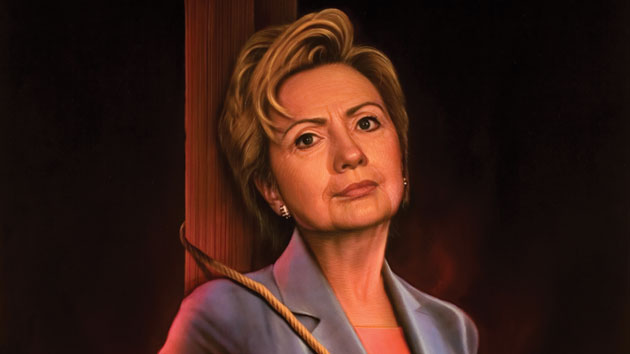

Illustration by: Tim O'Brien

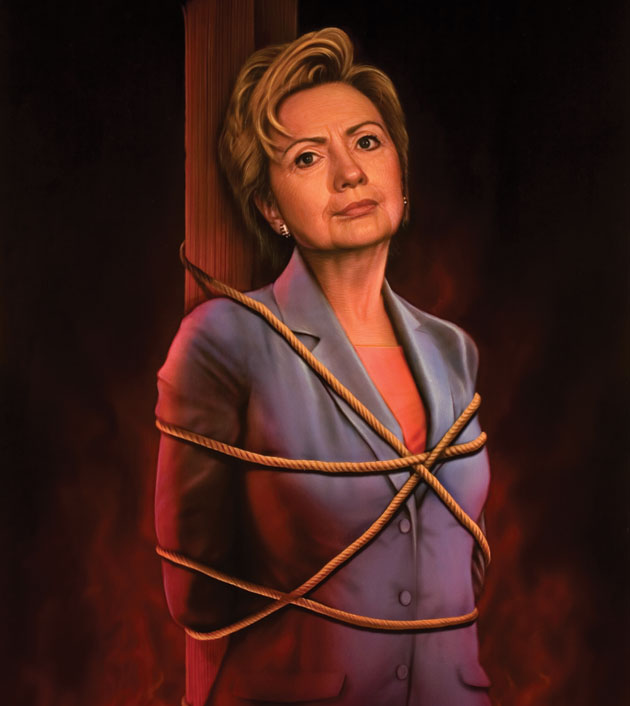

Illustration by Tim O’Brien

Daniel Edwards is that sculptor whose work includes a shiny dollop said to be the bronzed poop of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes’ baby, the severed head of baseball legend Ted Williams, and a nude Britney Spears in a primal birth position. A few months ago, the Museum of Sex in Manhattan unveiled his latest work: a bust of Hillary Clinton. Cast in the heroic style of the 19th-century statesman found in any City Hall park, it showed the New York senator with a long, elegant neck and solemn expression above two perfectly round, youthful, barely covered breasts. I’d guess a 36B.

“It was a quote by Sharon Stone that triggered it,” Edwards explained to me. Stone, an actress famous for exposing a different part of her anatomy, had recently expressed doubt that Hillary could become president because “a woman should be past her sexuality when she runs. Hillary still has sexual power, and I don’t think people will accept that. It’s too threatening.”

Edwards says he wanted to imagine Hillary Clinton as president of the United States and created, therefore, a monumental image. “But that wasn’t enough,” he explains. “I had to make sure she was depicted as a woman, unmistakably a woman. The way I did that was to be more revealing with her breasts than is normally seen.”

Edwards’ version of Hillary’s breasts is where it all gets interesting. He chose not to depict Hillary with bared breasts, in the classical style of Greek sculpture; his Hillary’s bust is upheld by a bustier worthy of Victoria’s Secret. “I didn’t want the sculpture to be titillating or a piece of graphic realism,” he explains. “It’s more symbolic of womanhood and to reveal her as a woman.”

Hillary’s “womanhood” is in need of public revelation? What does that say about her? But, more curiously, what does it say about us that Hillary inspires this casual intimacy? Her life, her looks, her politics, her marriage—and now her breasts—are all daily grist at the nation’s coffee shops, still, 15 years after she was introduced to America. According to one accounting, there are 17,000 websites devoted to Hillary Clinton. And there is really no aspect of our collective fears or furies that cannot be grafted onto her character. Did she refuse to meet with mothers of dead soldiers? Did she kill Vince Foster? Did she get two Black Panthers off on murder charges? Did she cause the Enron scandal? Despite their proven falseness, such accusations are routinely made because it’s easy to mold the facts and fictions of Hillary’s life into any kind of argument you like. Even her body has become a public landscape that most Americans feel quite comfortable trekking across in search of cultural clues about ourselves and our politics. Edwards’ sculpture merely makes literal this national impulse.

It all began when the nation had regular debates about her hair, but now we’re comfortable in our kitchens and on our talk shows presuming any damned thing we want to about her. Is she gay or straight, closet conservative or secret liberal, snarling she-wolf or one smart cookie baker? It isn’t only her career as a public figure that’s clay in our hands. No part of her life, however sacred, is off-limits. John McCain once got a lot of laughs cracking this joke: “Why is Chelsea Clinton so ugly? Because her father is Janet Reno.” Chelsea was still in high school at the time. In 2003 Americans happily participated in a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll to determine whether Hillary should get a divorce. In the spring of 2006, the New York Times ran a front-page story that employed investigative journalism tactics to extrapolate the potential number of conjugal visits the Clintons’ marital bed hosted each month. Using “interviews with some 50 people and a review of their respective activities,” the author concluded: “Since the start of 2005, the Clintons have been together about 14 days a month on average, according to aides who reviewed the couple’s schedules. Sometimes it is a full day of relaxing at home in Chappaqua; sometimes it is meeting up late at night…. Out of the last 73 weekends, they spent 51 together. The aides declined to provide the Clintons’ private schedule.”

Damn aides.

When Edwards fashioned Hillary into the image that he thought most telling, he was on to something. Hillary is way beyond something so banal as a politician. The details of her life are familiar enough; perhaps that’s why all the profiles of her over the last 10 years have always seemed tedious and repetitive. It’s how we shape those facts that’s interesting. Hillary herself once said she had become some kind of Rorschach blot in which Americans see many things.

Almost every American has an opinion about Hillary. Consider her poll numbers. Hillary Clinton has favorables in the high 40s right now and unfavorables running about even. Her “no opinion” numbers are in the low single digits, approaching zero. Most politicians start with a huge swath of “no opinion” voters whom they can then try to convert. If Hillary runs, she will need to invent a whole new form of campaign strategy: She will need to flip voters who pretty much hate her.

Hillary-hating is such a national pastime, for both Democrats and Republicans, that it should be its own verb: “Hillarating.” Typically, even her supporters make the case for her only after plowing through a lot of caveats, lessons learned, and after muttered contempt for some aspect of her person. Hillarating is not like normal political hating—opposing someone’s ideology, for example. Loathing Hillary happens on multiple levels, ranging from her marital choices and fashion sense to her ambivalence on torture or support for a flag-burning amendment. And liberal feminists are as comfortable Hillarating as anyone else, perhaps more so.

“The source of the strong feelings goes all the way back to when we were introduced to her as Bill Clinton’s copresident,” says Nora Bredes, director of the Susan B. Anthony Center for Women’s Leadership in Rochester, New York. After the health care defeat in 1993, Hillary retreated into being a wife and then a proper first lady before emerging again “as an international leader and then in the late ’90s re-creating herself as a victim of his infidelity and then again stepping out as a candidate for the Senate,” says Bredes. “People get uncomfortable when it’s not a neat story. Is she a progressive feminist or a cautious moderate? People don’t know exactly who she is, and so different reactions are almost invited.”

Not since Richard Nixon has the body politic been treated to so many variations on the same person. “The New New Nixon” was introduced with such frequency once upon a time that it became shorthand for a kind of political marketing joke. Hillary has assumed that cultural niche, always inventing a new look and more “humanized” self for each situation. And in turn, we’ve seized upon various elements of her changeling character to shape, à la Daniel Edwards, our own private Hillarys. She is a Cosmo quiz of an enigma, so let’s cut right to the answer key in the back pages and find out what kind of Hillary you see.

The Martha Stewart Hillary: For you, the New York senator is, as Newt Gingrich’s mother once observed, “a bitch,” or, as William Safire phrased it, “a congenital liar.” You tend to relish the catty details that reveal her as a petty-minded overachiever, like when she peevishly denied her ghostwriters writing credit. You believed the 2003 rumor that Wesley Clark had been ordered into the campaign by some Clinton consigliere to serve as her stalking-horse. In the mid-1990s, you wanted to buy that Jerry Falwell tape alleging that she bedded and then killed Vince Foster, had him rolled up in a rug and dumped along the Potomac. You snarkily refer to her by the name that grates most on those who despise her, Hillary Rodham.

The Tammy Wynette Hillary: The famous invocation of the country-western singer happened during a 60 Minutes interview in 1992. Hillary defended her husband’s philandering by saying, “I’m not sitting here some little woman, standing by my man like Tammy Wynette.” And this is where it can get tricky. Most people forget Hillary’s next line: “I’m sitting here because I love him.” The cognitive dissonance is confusing, because, of course, that is the Tammy Wynette position (“And tell the world you love him / Keep giving all the love you can”). When she dissed Tammy, she left the impression that the real reason she was standing by Bill was ruthless desire for power. Then after getting into hot water over health care reform, she assumed the Tammy position, that of doggedly loyal wife. This was the Hillary who beamed at Bill’s side and cut her hair in a prim, wifely fashion. Amid a flurry of sex scandals that would culminate in Monicagate, this Hillary allowed herself to be photographed in her one-piece bathing suit snogging with Bill on the beach—causing an entire nation to wince.

The Eleanor Roosevelt Hillary: This Hillary first emerged at her 1969 college graduation, when her commencement speech was considered so controversially feminist that it landed her in the pages of Life magazine. The speech sent Wellesley’s president, Ruth Adams, into such a tizzy that, after spotting Hillary swimming, she had a campus security guard run off with her clothes to humiliate her. This is the Hillary who figured out, after the health care train wreck, how to be a good first lady, and quickly became the “Most Admired Woman in America” several years in a row. This Hillary had an office in the East Wing that handled the protocols of napkin folding, and an office in the West Wing that adroitly kept up her silent participation in the crucial political issues of the day.

The Dianne Feinstein Hillary: You see her as a phony centrist always triangulating toward the ideological middle, willing to betray her true liberal self for power.

The Barbara Boxer Hillary: You see her as a phony liberal, always playing to the amen chorus of the far left, willing to betray her true centrist self for power.

The Lisa Simpson Hillary: We’re seeing of lot of this conscientious Hillary lately. When she ran for Senate, her critics said she was just running on name recognition. “But she was able to give milk prices to upstate New Yorkers,” says Helen Thomas, the former UPI reporter who has covered the White House since John Kennedy. “Then, in the Senate, she acted like Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, asking experienced Republican senators to ‘teach me’ how it all works.” This is the Hillary who got straight A’s; the law school graduate who in 1974 wowed the old D.C. pols on the Watergate Committee; the one who attempted to master health care in 1993; and who in 2000 visited Buffalo 26 times and earned its citizens’ votes. This Hillary first appeared at age four when, according to her mom, the future senator confronted the neighborhood’s meanest girl bully, knocked her down, and then exclaimed, “I can play with the boys now!”

The Diana Prince Hillary: Bill’s wife is the secret identity of Wonder Woman. Is there anything she can’t do? Even if you hate her, you admire her fundraising ability and her $8 million book advance. You hear that joke about Bill seeing Hillary chatting with an old boyfriend pumping gas at a filling station and Bill says, “Just think, if you’d married him, you could have been the wife of a gas station attendant,” to which Hillary replies, “Bill, if I’d married him, he would have become the president”—and you think it’s just good reporting.

The Lady Macbeth Hillary: You fixate on pictures of Hillary wearing big dark sunglasses, behind which she conspires to take over the world. Ruthless, conniving, calculating, icy, and manipulating, this Hillary crafted that phony post-Monica talking point—”I could hardly breathe”—as evidence of her “emotional side.” This Hillary spooked her potential senatorial opponent K.T. McFarland, a former Pentagon official, into charging that she “had helicopters flying over my house in Southampton today taking pictures.” This Hillary will abandon her principles for short-term political gain and will coldly undercut her oldest friends if need be—remember Peter and Marian Wright Edelman? This is the Hillary who, hours after hearing the truth about Monica, was in the solarium considering whether to help Bill’s speechwriters draft his dodgy confession. This version of the senator is known by the name that elevates her into the pantheon of scheming one-named women such as Medea and Evita. She is, simply, Hillary.

It’s not just that Hillary herself is seen in half a dozen ways, but that each variety of Hillary is embraced across the political spectrum. The word-association part of the Hillary Rorschach test fails as political litmus because everyone uses the same essential vocabulary. The language that one expects to hear from her right-wing critics—that she’s untrustworthy, two-faced, opportunistic, and scheming with a hidden agenda—you are just as likely to hear from other women in power, feminists, and people on the left. You expect to read Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan calling her a “cynical leftist political operative” who sees “our country as a platform for her core ambitions.” But you also get Cindy Sheehan comparing her to Rush Limbaugh; Susan Sarandon complaining, “What America is looking for is authentic people who want to go into public service because they believe strongly in something, not people who are trying to get elected”; and the late Wendy Wasserstein saying Hillary “has flip-flopped on so many issues of image that her behavior can justifiably be called erratic.”

Some of the more common adjectives hurled at Hillary are familiar to any high-achieving female. And, sure, the woman known in high school as “Sister Frigidaire” faces all the glass-ceiling, woman-in-a-man’s-job, underestimated, underpaid, overworked gender guff that also frustrates senators Olympia Snowe and Mary Landrieu. But what makes our reaction to her far more extreme?

More than any other public figure, Hillary forces us to acknowledge that the path to power for American women is not all that clear, more an odyssey than a march. The national trauma began when Hillary violated perceived roles of domesticity, says Betty Winfield, a University of Missouri professor who has been monitoring Hillary’s public perception since the campaign of 1992. “People had a very preconceived idea about how a first lady was supposed to act, the image of a supportive wife but not too outspoken,” says Winfield. “Hillary had no noblesse oblige cause, nothing coming from the domestic sphere like highway beautification or illiteracy or anti-drug use among teens. No, no. She was going to change the entire health care system for the whole country.”

This didn’t sit well, says Winfield, in part because “women who attain power or public recognition as satellites of great men are subject to a lot more criticism than women who arrive to the public arena on their own accomplishment.” (In her day, Dolley Madison was accused of being lascivious, Jefferson’s mistress, and trading sex for votes.) Of course, long before she was first lady, Hillary was already accomplished, having clawed her way up the law firm ladder to become the first female partner in Arkansas’ oldest and most prestigious firm. The closest parallel at the time was…Marilyn Quayle. How quickly we all forget that Marilyn was a law partner with her husband in a Clintonesque firm called Quayle and Quayle. When Dan was named vice president in 1988, the governor of Indiana offered to appoint Marilyn to fill out his term in the U.S. Senate. Hillary merely took up the work of bushwhacking a path originally macheted by a woman now almost entirely forgotten.

Like Quayle, Hillary had her career sights aimed high, so how awkward was it that when she ascended to the West Wing in 1992, it was via the highest bedroom in the land. Certainly it explains why she uttered such mortifying lines as the classic: “If you vote for my husband, you get me; it’s a two-for-one blue-plate special.”

That original confusion about her role persists. Typically, says Winfield, women in power are seen as “either the domineering dowager or the scheming concubine.” In the American psyche, Hillary is a two-for-one special, seen as both Election‘s Tracy Flick and a postmenopausal Margaret Thatcher power-Frau—despised for possessing sexuality and being devoid of it.

One of the first criticisms, says Edwards of his sculpture, “was that critics said the piece looked like ‘Jimmy Carter with boobs.'” Edwards notes that the Internet is a kind of Dantean pit of Hillary imagery; he describes his work as an attempt to rescue her femininity from the sexual inferno in which he discovered her. “Before I came along, there were all these Photoshopped images of her,” he says. “They’d take a lot of porn images and then splice her in. Oh my God…she’s had to have seen them.”

Most men, especially when women aren’t around, will typically open up a conversation about Hillary in precisely these terms. Long before they get to her politics, they gossip about her comeliness, and the judgment is always harsh. Busting Hillary back down to mere dame, and a rejected one whose sexual allures fail, seems to be a necessary preamble to any discussion of her. In October, her Senate opponent, John Spencer, accused her of being ugly. (He now officially denies it.) The Daily News quoted him as claiming that Hillary had spent “millions of dollars” on plastic surgery. “You ever see a picture of her back then? Whew,” Spencer said. “I don’t know why Bill married her.”

The point is, whether the real Hillary is brimming with sexuality or is entirely drained of it, any talk about her is always borne ceaselessly back to her intimacies, her appearance, her sexuality, her femininity. Why?

There are so many answers to that question, it’s one of the reasons the country can’t stop talking about her. But here is one: Hillary is an avatar of an existential dread skulking in the hearts of every couple who’ve tried to put together a life since the feminist revolution. This anxiety explains why the darkest question a liberal feminist can ask is: Why didn’t she leave that son of a bitch? And it’s why the coarsest question a conservative man can ask is: Who would do the bitch? Both point to deep fears that emerged alongside feminism, grounded, as every question since that revolution is, in the politics of the bedroom.

Hillary has come to embody a dark fear in the hearts of modern men: the wife who neglects the joys of the bedroom for her career. The middle years of marriage are hard enough (or so I have read), trying to keep the flame flickering amid the anxieties of bills, the call of career, the squall of little children. That’s the age-old stuff. Add to that a novel stress on the guy: a new destructive Oedipal force right at his side, his wife. She wants a career equal to, if not better than, her husband’s. Will she be more famous, make more money, hold more prestige?

And there’s Hillary, pushing onward, to where? The presidency itself. She could possibly pull off what George W. Bush has attempted: surpassing a familial predecessor in achievement and esteem. As always, we imagine, Hillary is watching and learning, waiting her turn.

The flip side to Hillary’s ambition evokes every career woman’s greatest fear. How fragile is marriage? It can come apart as quickly as that girl delivering the pizza can snap her thong. And there is no amount of superachieving or hard work that can prevent this lurking humiliation. Just ask the other Hillary: As Martha Stewart ascended to the heights of fame, her husband, Andy, pulled a Bill and started screwing one of the young office assistants. It’s absurd, sure. It’s clichéd and pathetic. But, for the working wife, trying to build a career off the foundation of her marriage to even the nicest (smartest, richest, handsomest) man, her worst fear is that he’ll stray in this, the most debasing of ways. It’s a complete denial of her womanhood, an essential insult. It’s why the kind of anger liberal women feel toward Hillary always circles back around to the issue of why she stayed in the marriage. Why didn’t she take a stand against male grossness?

Instead, she toughed it out. And she gets no love from any side for it. To the right, she stayed not for any principle or for Chelsea but because she’s a clawing shrew who will suffer any ignominy to attain power. To the left, she had a chance to take a stand for all the women who’ve been humiliated, and she didn’t. (Bill, it should be noted, is largely forgiven, even revered, by left-leaning women.)

But the more body blows Hillary withstands from critics (or her husband), the stronger she can look. Who can forget when Rick Lazio marched across a stage in 2000, shoved a campaign pledge in her face, and tried to strong-arm her into signing it? Hillary coldly asked him to step away. It was the turning point of that campaign. That motherfucker. Suddenly female voters saw in Hillary every woman who has had to put up with demeaning crap from men. And a lot of male voters simply saw an underdog standing up and rallied to her side. She crushed Lazio by 12 points. In November, John Spencer, who will be remembered only for calling Hillary ugly, went down to a defeat three times as ignominious.

It’s amazing to see just who can rush to Hillary’s side when the issue becomes the bare-naked question of trying to bring down a high-achieving woman. During a discussion of snipes at Martha and Hillary on Tina Brown’s TV show, Laura Ingraham, who once wrote a book called The Hillary Trap: Looking for Power in All the Wrong Places, confessed, “I’ve gone through that. I’m the right-wing info babe. That’s the box I’m put in…. Powerful women carry a heavier burden…. No one likes to see a woman get too powerful, too fast, too smart.”

Ask your friends if their fear and loathing of Hillary has anything to do with her being a woman, and you’ll undoubtedly get a denial. That might be someone else’s problem, but certainly not mine. But after a Lazio moment, or when John Edwards’ wife told guests at a Ladies’ Home Journal luncheon that her “choices” had made her “happier” and more “joyful” than Hillary, an epiphany can occur, as it did for The Nation‘s Katha Pollitt, who wrote, “If people keep making sexist attacks on Hillary Rodham Clinton, I may just have to vote for her. That means you, Elizabeth Edwards!” One has to wonder, especially considering the massive voter support she’s received in two elections, if Hillary doesn’t already have her own hidden vote: not just feminist columnists, but moderate and even Republican women who might exult in Hillarating until they step into the seclusion of the voting booth, where all the watercooler chitchat, pissy remarks, and catty complaints fall away to reveal a working woman getting harassed in a man’s world—and they recognize what they see.

Hillary is an icon of our most transformative personal revolution. Racial integration was about bringing excluded people to a metaphorical and literal lunch counter that was already there. A public place. But the feminist revolution was about remaking the private world, the nest and resting place for all us careerists.

Hillary explained it in that notorious speech at Wellesley in 1969. She said, “But we also know that to be educated, the goal of it must be human liberation. A liberation enabling each of us to fulfill our capacity so as to be free to create within and around ourselves.” She was in the first class of women’s libbers, back when “the Working Woman” was more an idea than a reality and the future held infinite possibility. She left Wellesley fired up with the rhetoric of Steinem and Friedan. They had revealed to the world the new theory; she would show them how it worked in practice. Hillary is the real revolutionary: She had a career. She had a family. She had a husband with a career. They were both ambitious boomers—perhaps the most ambitious. They wanted not just good jobs but the very best of all possible jobs. And every step of the way she demanded and got—to use the old-school rhetoric—the freedom to choose.

That language pops up with Hillary from time to time, such as one curious moment during her first Senate campaign when men and women, liberals and conservatives, all still had inflamed opinions on whether she should stay in her marriage or not. Asked after a speech about her decision to remain with Bill, she said: “I fought all my life for women to make their own choices, in their personal and professional lives. I made mine.”

How retro-1970s an answer is that? Hillary is still talking that talk and walking that walk, even though the revolution never really worked out as drafted. Those day care and health care support systems never arrived. Glass ceilings appeared, lower pay persisted. Feminism gained an angry militant opposition that now works to outlaw abortion state by state. Without widespread public support, the movement fell onto the shoulders of the individual women who could tough it out, women like Sister Frigidaire, the woman who could visit Buffalo 26 times. A lot of women just got tired. Many shrugged off the fight for full professional independence and happily went home to raise the kids. Feminists gamely tried to make the argument that their intention all along was to allow any of these fine choices to be made. But a lot of compromises were made all around. Now Gloria Steinem is like some oldest living Confederate widow occasionally showing up on TV to remind us what it was like, back in the day. Then, a certain ideal seemed inevitable—the feminist enjoying both the pleasures of motherhood and the Eisenhower-era man’s life of full professional reward. Of those idealists, Hillary is arguably the only one still in our face.

In her Wellesley speech, she concluded with a poem, a portion of which eerily captures the trajectory of the woman she would become: “And the purpose of history is to provide a receptacle / For all those myths and oddments / Which oddly we have acquired / And from which we would become unburdened / To create a newer world / To transform the future into the present.”

History’s receptacle. And an entire nation has been filling it with our myths and oddments ever since: Hillary Clinton. Who soldiers on, even as the rest of America has backed off from 1970s-style feminism just a little (or a lot). Once upon a time, to use the old-school rhetoric again, people like her said, “I can have it all.” She wholeheartedly believed it. She would like to have it all. And in two years, she just might get it.