Photo by Adam Shemper

Prisons were a relatively new concept in the early 1800s. Punishment for crimes had been a matter for communities until then. Some took the Hammurabian approach of an eye for an eye, and public hangings in town squares were the price for murder, rape, or even horse thievery. As a more nuanced judicial system evolved, civic leaders sought a more civilized method of punishment, and even began entertaining the idea of rehabilitation.

In 1790, Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia (built in 1773, but expanded later under a state act) was built by the Quakers and was the first institution in the United States designed to punish and rehabilitate criminals. It is considered the birthplace of the modern prison system. Newgate Prison in New York City followed shortly after, in 1797, and was joined 19 years later by the larger Auburn Prison, built in western New York state. All three were perhaps naive experiments in the very new concept of modern penology. They all began as, essentially, warehouses of torture. The gallows and stocks were moved inside, but little else changed. Those who survived generally came out as better-trained thieves and killers.

Between Philadelphia and New York, a schism in philosophies emerged: The Philadelphia system used isolation and total silence as a means to control, punish, and rehabilitate inmates; the Auburn or “congregate” system—although still requiring total silence—permitted inmates to mingle, but only while working at hard labor. At Walnut Street, each cell block had 16 one-man cells. In the wing known as the “Penitentiary House,” inmates spent all day every day in their cells. Felons would serve their entire sentences in isolation, not just as punishment, but as an opportunity to seek forgiveness from God. It was a revolutionary idea—no penal method had ever before considered that criminals might be reformed. In 1829, Quakers and Anglicans expanded on the idea born at Walnut Street, constructing a prison called Eastern State Penitentiary, which was made up entirely of solitary cells along corridors that radiated out from a central guard area. At Eastern State, every day of every sentence was carried out primarily in solitude, though the law required the warden to visit each prisoner daily and prisoners were able to see reverends and guards. The theory had it that the solitude would bring penitence; thus the prison—now abandoned—gave our language the term “penitentiary.”

Ironically, solitary confinement had been conceived by the Quakers

and Anglicans as humane reform of a penal system with overcrowded

jails, squalid conditions, brutal labor chain gangs, stockades, public

humiliation, and systemic hopelessness. Instead, it drove many men mad.

The Auburn system, conversely, gave birth to America’s first

maximum-security prison, known as Sing Sing. Built on the Hudson River

30 miles north of New York City, it spawned the phrase “sent up the

river,” meaning doomed. Although far different from Walnut Street,

Eastern State, and Auburn, in that inmates were permitted to speak to

one another, in many ways it was the most brutal prison ever built.

Various means of torture—being strung upside down with arms and legs

trussed, or fitted with a bowl at the neck and having it gradually

filled with dripping water from a tank above until the mouth and nose

were submerged—replaced isolation and silence. Sing Sing also held the

distinction of being home to America’s first electric chair.

Europe’s eyes were on the curious competing theories at Sing Sing

and Eastern State. A celebrity at the time, Charles Dickens visited

Eastern State to have a look for himself at this radical new social

invention. Rather than impressed, he was shocked at the state of the

sensory-deprived, ashen inmates with wild eyes he observed. He wrote

that they were “dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible

despair…The first man…answered…with a strange kind of

pause…fell into a strange stare as if he had forgotten something…”

Of another prisoner, Dickens wrote, “Why does he stare at his hands and

pick the flesh open…and raise his eyes for an instant…to those bare

walls?”

“The system here, is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary

confinement,” Dickens concluded. “I believe it…to be cruel and

wrong…I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the

brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.”

In the late 1800s, the Supreme Court of the United States began

looking at growing clinical evidence emanating from Europe that showed

that the psychological effects of solitary were in fact dire. In

Germany, which had emulated the isolationist Pennsylvania model,

doctors had documented a spike in psychosis among inmates. In 1890, the

High Court condemned the use of long-term solitary confinement, noting

“a considerable number of prisoners…fell into a semi-fatuous

condition…and others became violently insane.”

Prisons built after this period—including Angola—were designed more

as secure dormitories for captive laborers, as envisioned in the Auburn

system. Inmates were required to work together at prison industries,

which not only kept them occupied; it helped the institutions support

themselves. Sing Sing, for example was built on a mine and constructed

entirely of the rock beneath it by inmate labor.

Eastern State was a grand failure, and it was closed in 1971, 100

years after the concept of total isolation was abandoned. But what it

revealed about the torturous effects of solitary may have made the

practice attractive to those less concerned with rehabilitation and

more interested in retribution. Solitary in the 20th century became a

purely punitive tool used to break the spirits of inmates considered

disruptive, violent, or disobedient. But even the most retributive

wardens have rarely used it for more than brief periods. After all, a

broken spirit theoretically eliminates danger; a broken mind creates

it.

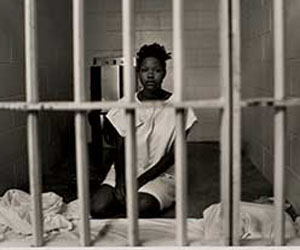

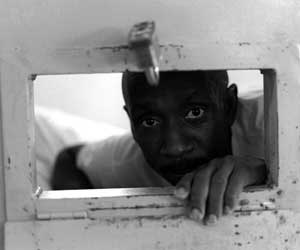

But in the past 25 years, the penal pendulum has swung back toward

the practices—absent the theories—that governed the “Philadelphia

system” invented at Eastern State. We no longer seem to have faith in

the “penitent” part of “penitentiary,” and our “corrections” system no

longer “corrects” anti-social behavior but inevitably breeds it. It can

be argued that today, almost all maximum-security prisoners in America

are kept in a kind of solitary for a large portion of their sentences.

The advent of “supermax” and “control unit” prisons in the early 1970s

has led to the construction of pod-based prisons and “security housing

units” in which all inmates are isolated one to a cell for most of

every day. They are generally allowed out for an hour each day for

exercise or a shower, and are permitted limited personal possessions

and visits. Many of the newer prisons enforce the “solitary” aspect by

keeping some prisoners in soundproof cells, so they cannot even talk or

shout at one another. The lack of regular human contact is still

considered inhumane by many rights advocates who have taken to the

state legislatures and courts to challenge its constitutionality.

Ironically, one of the loudest advocate groups is the National

Coalition to Stop Control Unit Prisons—a project of the American

Friends Service Committee, a Quaker group.