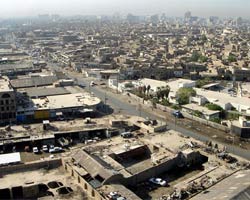

Photo: David S. Holloway/Reportage by Getty Images

In March 2003, Salam Adhoob, a prominent lawyer in the Iraqi city of Suwayrah, was glad to see US forces roll into his country. Iraqis, he felt, would be able “to rebuild our country again.” But when he saw looters ransack Baghdad’s National Museum on TV, he began to worry that the authorities could not protect his nation’s public resources. In the ensuing months, he was horrified as corruption ran rampant amid the postinvasion chaos. So when he was asked, in 2004, to join the Commission on Public Integrity (cpi), an independent Iraqi government agency charged with investigating official corruption, Adhoob enthusiastically accepted. He was soon pursuing high-ranking officials—as well as, in some cases, American contractors—involved in bribery, kickback schemes, oil smuggling, procurement fraud, and other wrongdoing. Eventually he became the country’s chief corruption investigator, overseeing 100 staffers who handled thousands of cases. “Now I could protect public money and help make the country work,” he recalls.

“He was a Boy Scout,” says James Mattil, a former chief of staff for the Office of Accountability and Transparency, a small unit in the US Embassy assisting the cpi. “He strictly enforced the law, regardless of whose toes he stepped on.” An Iraqi minister, Adhoob recounts, once tried to buy him off by offering up jobs for his family. “I told him, ‘I am in your office because I have a case. I just want you to allow me to do my work.'”

Today, two years after escaping Iraq amid death threats, the soft-spoken 45-year-old lives with his wife and their four children in a modest brick rambler (on loan from a local church) in a Washington suburb. Adhoob has no income. He’d landed a job as an Arabic instructor for the State Department, but was terminated after testifying on Capitol Hill that the US government has ignored the theft of at least $9 billion in US taxpayer dollars—some of it funneled to insurgents who killed American soldiers.

Adhoob cannot return to Iraq, where he would likely be killed. He feels betrayed by the US government, in whose promises he once placed such hope. His tale illustrates the tremendous difficulty of establishing the rule of law in Iraq—and the lack of commitment by the US to stamp out corruption.

Adhoob and his colleagues didn’t lack for work. “For investigators at the fbi or Customs, a $2 million case is a significant case,” says Kenneth McNamara, a former US Customs agent who worked with Adhoob. “For cpi, these were almost throwaway cases. They went after cases involving hundreds of millions, if not billions, of embezzled dollars.” The administration of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a target of many of the cpi‘s probes, issued numerous orders obstructing the commission’s investigations. In response, staffers held a one-day strike, and Adhoob led a demonstration in front of parliament. “I thought this was one of the best instances of democracy taking root,” says Mattil. Adhoob and the cpi, McNamara says, were “the only shining light of honesty within the Iraqi government.”

In the spring of 2007, the Maliki administration ordered the head of cpi, Judge Radhi al-Radhi, to fire Adhoob, according to Mattil, but Radhi refused. Worse, Adhoob and Radhi were receiving death threats. As McNamara notes, Adhoob was going after targets who “had their own militias. He was a marked man. There were late-night knocks on his door.” Some evenings, Adhoob slept in his office rather than risk the trip home. At times, he even needed armed guards at his Green Zone apartment. “The Green Zone was the center of the corruption,” he explains.

Adhoob’s fears were well warranted. Thirty-two of the cpi‘s 200 employees had been killed. Adhoob’s father-in-law, who had furtively ferried him about Baghdad, was murdered. And a few months after Maliki asked for Adhoob’s dismissal, Mattil says, the US Embassy confirmed a report obtained by the cpi that a death squad had been organized to take care of the government’s political enemies—including cpi officials.

Around this time, a group of American former law enforcement officers tasked with training cpi investigators asked the head of the US Embassy’s accountability office, Art Brennan, to protect Adhoob and Radhi. The State Department, they said, had declined to help. That upset Brennan, a Republican retired judge from New Hampshire, who was already worried that senior officials, including Ambassador Ryan Crocker, were not truly committed to addressing corruption in the Iraqi government. After all, he notes, much of the embassy’s staff was busy trying to build good relations with many of the same politicians Adhoob was investigating. “We were advising officials like Salam, teaching them how to investigate within the rule of law,” Brennan remarks. “They were actually doing it at great risk to themselves and their families, and no one in the State Department was really serious about it.”

That summer, when Radhi was in the United States for training sessions, Maliki ousted him as cpi chief. Radhi decided to stay in America—where he publicly compared the Maliki administration to the Mafia and declared that government officials had stolen more than $12 billion. With Radhi gone, Adhoob says, Maliki’s office again ordered the cpi to fire him.

At the time, Adhoob was working several big cases—from a Maliki aide suspected of embezzling school-construction money to a relative of a high-ranking defense ministry official who had managed to obtain $1.2 billion in military contracts, many of which weren’t fulfilled. Stripped of his job, Adhoob would not be able to pursue any of this. And he and his family would have to move out of the Green Zone, becoming easy targets for the assassins.

Adhoob holed up in a trailer in the US Embassy compound while his friends worked the byzantine process necessary to win him a US visa. After several weeks, word finally came: Can you be ready to leave Iraq in the next 90 minutes? The family grabbed their possessions and hurried to the airport.

Once in the US, Adhoob and Radhi applied for asylum. But senior US Embassy officials sent out emails directing staff not to write letters in support of their asylum request—to avoid, Brennan says, annoying the Maliki administration. “This was treachery to me,” says Brennan. “They knew Radhi and Salam were in great danger.”

The asylum requests were granted nonetheless. Adhoob says he’d expected to get a job with the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, the US military unit investigating American corruption in Iraq. But sigir chief Stuart Bowen Jr. says that Adhoob was never promised employment, though he has “continued to meet with sigir agents and to provide information on a significant ongoing case.”

“Sad to say,” remarks a former embassy official, “Salam became just another Iraqi émigré.” Last June, Adhoob did get a job as an Arabic instructor for the Foreign Service Institute. But his troubles weren’t over. On September 22, he testified about Iraqi government corruption before the Senate Democratic Policy Committee. Adhoob told the senators that “based on the cases that I have personally investigated, I believe that at least $18 billion have been lost in Iraq through corruption and waste, more than half of which was American taxpayer money.” He cited specific instances of sleaze: $24.4 million spent on an electricity project that existed only on paper; a front company run by the brother-in-law of a Ministry of Defense official being paid $4.5 million for the same helicopters that were purchased for $1.5 million just a few years earlier; and Iraqi ministries’ fraudulently paying contractors for “phantom projects.” He also maintained that an American company had delivered only one-third of the 510 Humvees it had been paid to supply the Iraqi military. (In mid-February, Adhoob notes, a sigir investigator informed him that this case was close to producing an indictment.)

Coming in the midst of an economic collapse and a red-hot presidential campaign, the hearing caused little stir. Still, Adhoob’s superiors apparently noticed. The next day, he says, his supervisor at the Foreign Service Institute told him that higher-ups wanted to talk about his Capitol Hill appearance. Adhoob demurred, saying his testimony was unrelated to his job. Soon afterward, he was notified that the institute would not renew his contract.

Ironically, at the time Adhoob was providing language instruction to Joseph Stafford, the former US ambassador to Gambia, who was preparing to serve as the new anti-corruption coordinator at the US Embassy in Baghdad. In a reference letter, Stafford later praised Adhoob as a “superb language instructor” and hailed him for having “battled heroically against corruption.” (A spokeswoman for the institute said she could not discuss Adhoob’s case.)

Art Brennan says he feels “very embarrassed by how Salam has been treated by the government.” For him, Adhoob’s plight symbolizes much of the United States’ postinvasion endeavor in Iraq: noble rhetoric undermined by neglect and hypocrisy. Mattil concurs. “Salam’s story,” he says, “contradicts the claims that Prime Minister Maliki has the political will to fight corruption and calls into question the whole mission in Iraq.” (In the fall of 2007, Mattil was relieved of duty a day after appearing for a formal interview with congressional investigators probing Iraqi corruption. He has since filed a whistleblower complaint against the State Department.)

With Adhoob and Radhi gone, the Maliki government has had an easier ride. Last fall, Maliki summarily fired inspectors general in various ministries. “The corruption problem in Iraq is worse than it’s ever been since the invasion,” says sigir‘s Bowen.

Pacing barefoot in his barely furnished living room clad in a dark sweater and pleated black trousers, Adhoob says he likes his new neighborhood, and his kids are enjoying the local schools. But he’s worried about the future—he’s been told he can only stay in the house until the end of the year—and haunted by the cases he can no longer pursue. Holding a folder with documents pertaining to his unfinished investigations, he says, “Sometimes I can’t sleep because of all this crime. Americans and Iraqis died because of this corruption. The Iraqi government is a group of criminal people who were supported by the Bush administration. I came here to tell American people the truth.”

He pauses before adding, “No one here cares.”