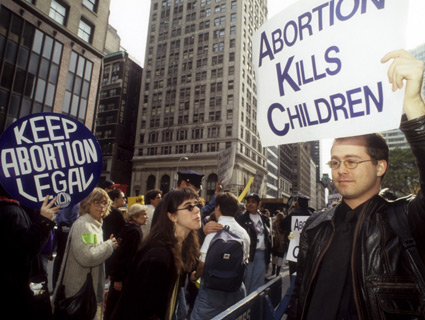

Frances M. Roberts/UPPA/ZUMA Press

Generally speaking, the Republican Party isn’t known for its stalwart defense of civil rights these days. The party has helped to obstruct legislation that would require equal pay for women. In 2006, many congressional Republicans voted against renewing the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the landmark civil rights law that helped ensure equal access to the ballot box. But lately, Republicans have enthusiastically embraced the expansion of anti-discrimination laws to at least one category of individuals: those still in the womb. Their sudden interest in civil rights for the unborn is part of a broader anti-abortion strategy designed to ultimately overturn Roe v. Wade by passing legislation aimed at abortion restrictions that are supported by a majority of the public.

To that end, for the third time in as many years, Republicans in the House are considering the Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass Prenatal Nondiscrimination Act, which would ban abortion based solely on the race or gender of the fetus. The bill was introduced by Rep. Trent Franks (R-Ariz.), who has made fighting abortion his life’s crusade. “This is the civil rights struggle that will define our generation,” he declared at a December hearing on his bill in the House subcommittee on the Constitution.

The bill ostensibly concerns itself with the plight of the black community, where, according to the legislation, “race-selection abortions have the effect of diminishing the number of minorities in the American population and therefore, the American electorate.” The Republicans who wrote the bill are also concerned that women are exterminating their gender through sex-selection abortions, which they claim is causing “unnatural sex-ratio imbalances within certain segments of the United States population…”

The bill’s language invokes the nation’s great struggles for racial and gender equality, noting that “the elimination of discriminatory practices has been and is among the highest priorities and greatest achievements of American history.” And it takes its constitutional authority from, among others, the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. Franks has even suggested that abortion has been more harmful to the black community than slavery. “Far more black children, far more of the African-American community is being devastated by the policies of today, than were being devastated by the policies of slavery,” he said last year, a comment roundly condemned by civil rights groups.

The Republicans’ sudden civil rights jag hasn’t gone over especially well with many of the groups that the GOP is claiming to protect, particularly African-Americans. Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), who was in Selma, Alabama, in 1963 for the Freedom Day voting registration drive, has expressed his displeasure at the GOP’s invocation of Frederick Douglass in the bill’s title. “I’ve studied Frederick Douglass more than you, and I’ve never heard or read about him saying anything about prenatal non-discrimination,” he told Franks at the recent hearing on the bill.

The prenatal discrimination bill is problematic in a number of ways, which is probably why it never made it out of committee in the last Congress. Among other things, it allows relatives of a woman who has an abortion, including her father or husband, to bring a lawsuit against the abortion provider if they suspect the procedure was performed for race or gender reasons.

It’s also unclear how the law would be enforced. Health care workers, including nurses, would be required under the law to report “suspected” violations or face criminal penalties. Reproductive rights advocates believe that in practice it would create widespread racial profiling and discourage abortion providers (or anyone providing prenatal health services) from treating women for fear of running afoul of the law.

Sarah Lipton-Lubet, an attorney in the ACLU’s Washington legislative office, points to the requirement that health care providers report suspicions that the law has been violated. “So what does that even mean?” she asks. “What makes one woman more suspect than another? Is it the way she looks? Is it her ethnic background? It almost seems to suggest that folks should be going on a witch hunt.”

Both the ACLU and the Center for Reproductive Rights believe the bill is blatantly unconstitutional, in part because it would force health care providers to question a woman’s reason for undergoing a legal procedure, in effect criminalizing an element of free speech.

The bill’s myriad legal problems haven’t kept Republicans from trying to get it passed. That’s because it’s part of a larger strategy to ultimately overturn Roe v. Wade. The conservative legal scholar Steven Calabresi sketched out the strategy in a Harvard law journal article in 2008, arguing that the key to eroding Roe was to pass state and federal laws that “restrict abortion rights in ways approved of by at least fifty percent of the public,” including sex-selection abortion bans. After all, the public is firmly opposed to aborting babies based solely on their gender. The bill also seems aimed at dividing the African-American community and weakening its historic support for the Democratic Party.

Several states have enacted bans on gender-selection abortion, but so far only Arizona has passed a law criminalizing race selection as well. That bill passed in March, with help from an undercover recording made by the anti-abortion group Live Action, which purports to show Planned Parenthood workers agreeing to take donations that were offered by donors who specified that they only wanted their money to be used to abort black babies.

Last year, Georgia lawmakers tried to pass a law similar to Franks’ federal proposal. The campaign started with controversial billboards, which began popping up in the state after President Obama was elected. They featured a photo of a beautiful, sad black baby boy and the line: “Black children are an endangered species.” Anti-abortion activists claimed to be out to save the black community from genocide at the hands of Planned Parenthood.

“The most pernicious part was, they’re trying to hijack the civil rights legacy in the service of conservative causes, trying to appropriate the mantle of the civil rights movement in a really despicable way,” says Loretta Ross, the national coordinator of SisterSong, a reproductive justice organization for women of color in Atlanta. She says the effort even featured white people singing “We Shall Overcome” at black women as part of a pro-life “freedom ride” bus tour that stopped at Atlanta’s Martin Luther King Jr. Center.

But the debate over the bill unexpectedly highlighted some of the racism inherent in the legislation, with Georgia Republicans threatening to vote against it because it only protected black babies. The issue was so divisive even among Republicans that the GOP House speaker refused to bring it to the Legislature’s floor.

Meanwhile, right-to-life groups are pressing forward with the federal bill and lobbying other states to pass similar laws. But if they are hope that the state laws will clear a path to the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, they may be disappointed. That’s because the laws are so vague and unworkable that it’s highly unlikely anyone has been—or will be—prosecuted under them.

Franks told me he was certain people have been prosecuted under the existing laws, but that the “other side” was afraid to challenge those cases in court, lest they create a bad precedent that might help overturn Roe. But I could find no instance of anyone ever being prosecuted under the law in Arizona, or in other states that ban gender-based abortions. The National Abortion Federation, which represents abortion providers, likewise said it could not find any evidence that any of its members had been affected by these laws.

It’s no surprise, really. As Ross points out, “It’s kind of hard to find evidence that a black woman is going to have an abortion because she’s surprised to find her baby is black. It just strains credulity to think that’s a problem,” she says with a hearty laugh. “I mean, she wakes up in the morning and says ‘Oh my god! My baby’s black?'”