Anti-ALEC poster from a protest in Scottsdale, Arizona, in November 2011<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/soozarty/6442660519/in/photostream/">Soozarty1</a>/Flickr

Much of the recent controversy surrounding the American Legislative Exchange Council has focused upon the way it brings together its key members, major corporations and state legislators, to craft legislation behind closed doors. Largely unnoticed has been the influence wielded by a third group of ALEC members: think tanks.

Two of those state-level think tanks took center stage at last weekend’s ALEC Task Force Summit in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Arizona-based Goldwater Institute and the Michigan-based Mackinac Center for Public Policy successfully shepherded five model bills through ALEC’s Commerce, Insurance, and Economic Development Task Force—all targeting public-sector unions.

Goldwater representative Byron Schlomach introduced two bills, one requiring that public employees annually approve their employer’s automatic deduction of union dues from paychecks. Another would prohibit union officials from taking paid leave from public-sector jobs to perform union duties.

The Mackinac Center sent labor policy analyst Paul Kersey to introduce three more bills targeting unions. One of those model bills is already Michigan law, requiring public-sector unions to make public audits of their financial activities. Another Mackinac proposal would require public-sector union members to vote on their union membership every three to five years, and a third would make it easier for public and private employees to decertify their unions.

Members of the ALEC’s commerce task force confirmed that the five union bills were approved in Charlotte. Amid heightened scrutiny, ALEC restricted press access and shortened the summit to one day. ALEC did not return calls requesting information.

The think tanks’ bills will become model legislation if the group’s board of directors does not initiate a formal review of the bills within 30 days. ALEC will then likely encourage its member legislators to introduce the model bills back in their home states. Since its founding in 1973, ALEC has successfully pushed hundreds of laws at the state level. According to the its website, every year legislators introduce nearly 1,000 bills based on ALEC model legislation, and 20 percent of them become law.

Dozens of state-based think tanks, many of them part of a Heritage Foundation-affiliated umbrella group called the State Policy Network, have long held sway within ALEC. “A very large proportion of the bills are sponsored by these think tanks,” says Nick Surgey, a legal associate at Common Cause, which claims ALEC is actually a lobbying group and is violating its nonprofit status. “But behind that next layer is another set of unknowns about who is pushing the think tanks’ agenda.”

Goldwater and Mackinac are both part of the State Policy Network, which is headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, and boasts 59 member organizations across all 50 states. The network was founded in 1992 “at the urging of Ronald Reagan.” The group is a sponsor of ALEC events and made grants to 18 free-market organizations in 2010, including $25,000 to the Mackinac Center. In 2008, it gave $50,000 to Mackinac and $30,000 to Goldwater.

Some, though not all, of Goldwater and Mackinac’s other financial supporters have been revealed. They have been supported with grants from the Charles Koch Charitable Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, and the State Policy Network—groups that also fund ALEC. Together, Goldwater and Mackinac draw money from 12 of the same conservative foundations, according to analysis by Media Matters Action Network. In 2010, the last year for which information is available, the think tanks had budgets of approximately $3.5 million each.

Before the union bills were approved at ALEC’s conference last weekend, some of them were sponsored in the Arizona and Michigan legislatures by ALEC members. “Arizona is a petri dish for extreme legislation,” says John Loredo, a Democrat and former minority leader in the state House of Representatives.

The Arizona Legislature has one of the largest contingents of ALEC legislators in the country. The last eight Arizona Senate presidents have been ALEC members, including former Sen. Russell Pearce, who sponsored the SB 1070 immigration bill, which later became ALEC model legislation and is currently under review by the US Supreme Court.

In the last legislative session, which ended May 3, the Phoenix-based Goldwater Institute advocated for a package of bills targeting public-sector unions that was sponsored by ALEC member Sen. Rick Murphy. The bills included the two introduced by Goldwater at ALEC’s Charlotte conference to prohibit paid union leave and require employees to authorize the deduction of union dues.

None of the bills, though, became law in Arizona. Goldwater and union representatives squared off in testimony while the Legislature considered the bills. At a Senate committee hearing on SB 1485, which would have ended bargaining for public employees, Nick Dranias, the director of the think tank’s Center for Constitutional Government, said “collective-bargaining laws threaten the very foundation of our republic.” The committee recommended the bill for passage, but it did not come to a vote before the full Legislature.

“We believe these bills are just a balancing measure,” says Goldwater president Darcy Olsen. “It doesn’t take away the voice of public employees, it just puts them on a par with the rest of the taxpaying citizens of Arizona.”

A separate bill to restructure hiring and firing practices for public sector workers became law in May. Gov. Jan Brewer had vowed to make it a legislative priority at a Scottsdale ALEC summit in 2011. Sponsored by an ALEC member, Rep. Justin Olson, the law allows state employers to fire public-sector employees “at-will,” with no right to appeal.

Sheri Van Horsen, president of American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees Local 3111, said the state’s unions are considering a legal challenge or ballot referendum to overturn the law. Because it exempts public-safety unions, Van Horsen argues that it is unconstitutional under the federal Equal Protection Clause.

Of the three model bills that Mackinac’s Kersey introduced at the recent ALEC conference, only one has become law in Michigan—a provision requiring every union to post an audit of its financial activity online. The think tank’s other two bills have not been introduced in the Michigan legislature.

Kersey says his model bill, the Election Accountability for Municipal Employees Act, would set up a schedule by which public-sector employees vote on unionization every three to five years, and would require a majority of all eligible union members—not just voting members—to maintain union representation. His other bill would alter the requirement that at least 30 percent of workers in a bargaining unit approve a petition to vote on ending union representation. Kersey’s model bill would lower that requirement to 10 percent and would apply it to both public- and private-sector unions.

The Mackinac Center has played a key role in pushing Michigan’s Republican-controlled Legislature to outlaw collective bargaining for public unions, supporting Gov. Rick Snyder’s year-old “emergency manager” law, which has ended public-sector bargaining in a handful of cities where the state has appointed a fiscal manager. The emergency manager in Pontiac, a former Mackinac Center adviser, abrogated city contracts with police and firefighters unions last year.

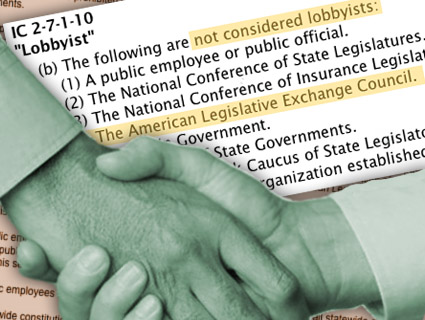

Like ALEC, Mackinac and Goldwater centers have been accused of crossing the line between public-policy research and lobbying. Common Cause has filed a complaint with the IRS, calling upon ALEC, which files as a 501(c)(3) public charity, to register as a lobbyist. The state-based think tanks are also under scrutiny for frequent correspondence with legislators and testimony at state capitols, and for drafting model bills like the ones brought to ALEC last weekend.

In April, Michigan Democratic Rep. Sander Levin asked the IRS to review the Mackinac Center’s advocacy role and evaluate whether indeed it should retain its tax-exempt, public-charity status. Levin referenced emails in which Mackinac advisers gave state lawmakers detailed advice on legislation that would cap the state’s health care payments to public-sector employees. The emails concluded with a message from Mackinac’s senior legislative analyst Jack McHugh, who wrote to Republican legislator and ALEC member Tom McMillin that “our goal is to outlaw government collective bargaining in Michigan.” IRS officials told Levin’s office they would take a closer look at Mackinac’s tax status.

The think tank has denied any wrongdoing. “We are 100 percent confident that we have complied with all laws pertaining to our 501(c)(3) status,” Mackinac’s vice president for communications Michael Jahr told the Lansing-area Daily Press & Argus.

Last year, Arizona’s secretary of state sent Goldwater letters asking the think tank to register as a lobbyist. “We believe you’re lobbying, you should sign up,” Assistant Secretary of State Jim Drake told the Arizona Republic. Following the letters from the state, however, Goldwater did register some of its representatives as lobbyists.

“I know people look at us and say this must be coordinated effort,” says Goldwater’s Olsen. “That is not how we operate. We’re not a lobbying organization, we’re not doing guerrilla warfare—we’re a think tank.”