<a href="http://practice.motherjones.com/slideshows/2011/05/california-prison-overcrowding-photos/cramped-conditions#">California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation</a>

In 1996, Shane Taylor, a 27-year-old prep cook and married father, was arrested in California’s Tulare County for possession of $5 worth of methamphetamine. If charged as a felony—as it was in this case—such an offense carries a minimum sentence of 16 months in prison. But Taylor had been convicted twice in the late ’80s on felony burglary charges, so his petty meth possession earned him a life term under the state’s “three strikes” law.

Howard Broadman, the retired Republican judge who sentenced Taylor to life, has come to deeply regret his ruling. “I made a mistake and I’m sorry,” he now says. (See video below.) Along with a surprisingly bipartisan group of prosecutors and law enforcement officials, Broadman is supporting Proposition 36, a California ballot measure that would limit three-strikes offenses to serious and violent crimes.

Taylor’s story was recently featured in one of a series of powerful shorts by Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega, creators of the Emmy-nominated documentary Better This World, which I wrote about as part of our award-winning package on FBI informants. Here’s the Taylor video, which first appeared as a New York Times “op-doc“:

A second video features Kelly Turner, a three-strikes inmate who was released on a technicality, and then went on to be a productive citizen:

The three-strikes law, approved overwhelmingly by California voters in 1994, coincided with a dramatic, nationwide drop in crime that had begun three years earlier and continued unabated for more than a decade. But the punitive new measure (and a similar law in Washington state) sparked a new era of one-upmanship by elected officials desperate to demonstrate that they were tough on crime. Today, 24 other states and the federal government have three-strikes laws in place, and being “soft on crime” is considered a third rail of American politics.

Or at least it was before Prop. 36 came along.

According to a poll released last week by the California Business Roundtable, 72 percent of California voters support Prop. 36—the same percentage that backed California’s original three-strikes law 18 years ago. So why have voters’ fears of bad guys on the loose given way to concern about locking so many of them up?

One reason could be the specter of a $28 billion state budget deficit, nearly $9 billion of which comes from paying for the state’s overcrowded prison system. Among other things, Prop. 36 would grant new sentencing hearings to 3,000 prisoners who committed nonviolent crimes but received lengthy prison terms under three strikes. The state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst estimates that this and future sentence reductions would save $70-$90 million a year.

The savings have caught the attention of some powerful small-government Republicans. The initiative’s endorsers include Grover Norquist, the president of Americans for Tax Reform, and George Schultz, the Nixon-era treasury secretary and former chairman of Ronald Reagan’s Economic Policy Advisory Board. “Conservatives know that it is possible to cut both crime rates and costly incarceration rates,” says the website of the prison reform group Right on Crime, whose members include Norquist and politicians such as Newt Gingrich and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush.

Yet thrift may not be the deciding factor: A September poll conducted by the University of Southern California and the Los Angeles Times found that learning about the proposition’s fiscal impact had no effect on voters’ willingness to back it. “The cost savings are there, but that’s not why people are supporting it,” says Michael Romano, the founder of the Stanford Three Strikes Project, which challenges California three-strikes sentences in court. “It’s because fair and proportionate sentencing really resonates with people.”

Romano ticks off some of the petty crimes that have landed defendants in prison for 25 years or more: possessing one-tenth of a gram of meth (a tenth the volume of a sugar packet), reaching in a window to steal children’s clothes off a table, shoplifting a pair of work gloves from Home Depot, stealing a dollar from a parked car, and possessing a stolen car radio. “As a matter of common sense and fairness,” Romano says, “we don’t think that repeat offenders of nonviolent crimes should get longer sentences than rapists and murderers.”

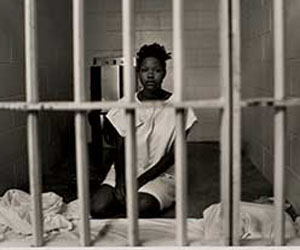

Bernice Cubie, featured in the video below, is serving life in a California prison for a third strike of possessing less than $10 worth of cocaine.

Opponents of Prop. 36 point out that judges and district attorneys can already opt not to assign strikes to accused criminals. They predict mayhem if the law passes. “Prop. 36 is kind of like a Pandora’s box being opened,” says Ron Cottingham, the president of the Peace Officers Research Association of California, which represents 64,000 public safety workers. “These are people with criminal records, and they will prey on the people of California, guaranteed.”

And yet there’s no evidence to suggest that curtailing three strikes will cause a crime wave. In 2000, Los Angeles County effectively implemented its own version of Prop. 36 when its newly elected Republican district attorney, Steve Cooley, stopped pursuing life sentences against third-strike offenders charged with minor nonviolent crimes. Today, crime in the county is at a 60-year low. “I am a great supporter of the three-strikes law,” Cooley told me, but Prop. 36 “is a very modest reform that streamlines a very good law and limits its potential for abuse.”

Whether other states will reexamine their own laws in the wake of Prop. 36 remains to be seen. Far from overturning three strikes, Prop. 36 would simply bring California’s law in line with most other states, whose three strikes laws were always limited to violent offenses. In any case, Romano thinks the measure’s bipartisan support may presage a national political shift: “The success of Prop. 36 with the support of prosecutors and Republicans will hopefully change the conversation from criminal justice politics—what is good at getting you elected—to criminal justice policy: What works, what is fair, and what helps keep the crime down.”

READ MORE: Shane Bauer’s exposé on solitary confinement, photographs of California’s overcrowded prisons, and Jennifer Gonnerman’s take on why we lock up 1 in 100 Americans.