Photoillustation by Matt Connolly

Video game company Electronic Arts announced Thursday that its popular line of NCAA football games would be discontinued, leaving July’s NCAA Football 14 as the seeming last iteration of the series. Cam Weber, EA Sports’ GM of American football, posted the death notice on the company’s blog:

Today I am sad to announce that we will not be publishing a new college football game next year, and we are evaluating our plan for the future of the franchise. This is as profoundly disappointing to the people who make this game as I expect it will be for the millions who enjoy playing it each year. I’d like to explain a couple of the factors that brought us to this decision.

We have been stuck in the middle of a dispute between the NCAA and student-athletes who seek compensation for playing college football. Just like companies that broadcast college games and those that provide equipment and apparel, we follow rules that are set by the NCAA—but those rules are being challenged by some student-athletes. For our part, we are working to settle the lawsuits with the student-athletes. Meanwhile, the NCAA and a number of conferences have withdrawn their support of our game. The ongoing legal issues combined with increased questions surrounding schools and conferences have left us in a difficult position—one that challenges our ability to deliver an authentic sports experience, which is the very foundation of EA SPORTS games.

The dispute in question is a far-reaching one that experts say could fundamentally change the way college athletics are run. It began in 2009 with two former college athletes—ex-UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon and ex-Nebraska quarterback Sam Keller—filing lawsuits against the NCAA, the Collegiate Licensing Company (which handles trademark licensing for the NCAA and about 200 colleges), and EA. The lawsuits were eventually consolidated and began to snowball, with other athletes joining in or filing suits of their own.

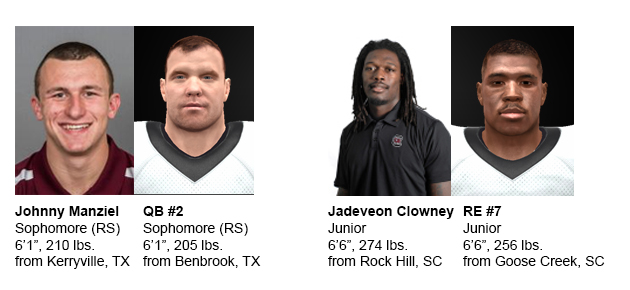

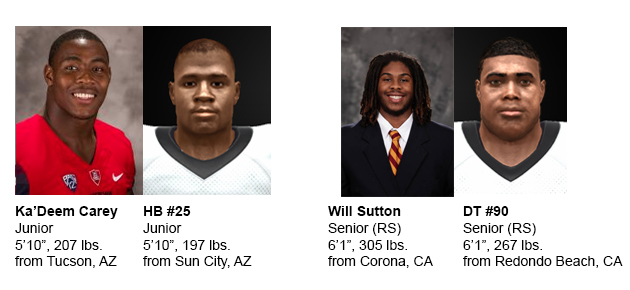

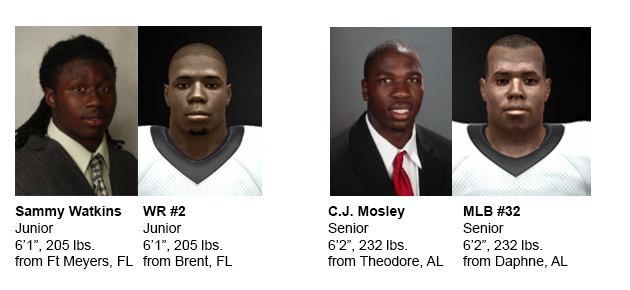

Because college athletes are amateurs, the NCAA forbids them from using their status or fame to profit it any way (taking compensation, the thinking is, would make them professionals). That’s what would have prohibited Heisman-winning Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel from theoretically accepting money in exchange for autographs, and it’s what got Ohio State in trouble when players received cash and free tattoos in exchange for rings, jerseys, and other memorabilia. Colleges, similarly, can’t monetize the likenesses of current athletes. Texas A&M can sell a No. 2 football jersey, but if that jersey can’t say “Manziel” on the back.

While EA can and does license the names and logos of colleges, stadiums, and bowl games, it’s forbidden from using the identities of current players in its college football games. In one of the more shameless legal workarounds since man first put a liquor bottle in a brown paper bag, EA gives in-game players nearly identical numbers, positions, physical attributes, and abilities as their real-life counterparts—everything but the names, save for a few dreadlocks.

With litigation looming, this practice was unsustainable. EA settled the O’Bannon-Keller lawsuit along with two others and cut the cord on next year’s game. In the future, the company will have to either randomly create its rosters—disappointing anyone who wants to toss touchdowns as a virtual Johnny Football—or do away with the series as we know it.

The loss of NCAA Football 15 (and possibly beyond) is a major development, but hardly the endpoint of the legal trouble facing big-time college athletics. Despite EA’s settlement, the NCAA has vowed to take the fight all the way to the Supreme Court. That’s because the O’Bannon-Keller lawsuit hits the NCAA right at its core—television revenue. The NCAA made more than $700 million in television and marketing rights fees from 2011 to 2012, none of which went to players’ pockets (since they’re amateurs and all).

While the lawsuit focuses on former athletes whose likenesses appear in game rebroadcasts, DVD highlights, and apparel, there’s an even larger implication for college games on television. This season’s Texas A&M-Alabama matchup drew 21 percent of that night’s television viewers. If players are given a cut of the revenues they helped generate, it would require a complete reworking of the way the NCAA does business. Some players are already calling for part of that money to go toward increased scholarship aid and medical coverage.

While that may piss some people off, it’s something the college sports world, EA included, is taking very seriously.