Until Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) rode to the rescue this week, Pentagon brass and their allies had been issuing dire warnings about the nation’s military readiness: The armed services were being decimated, they said, by sequestration—the automatic budget cuts that were set to trim $1 trillion from the Pentagon budget over the next decade. “It’s one thing for the Pentagon to go on a diet. It’s another for the Pentagon to wear a straitjacket while dieting,” grumbled Rep. Jim Cooper (D-Tenn.). The message got through: The House overwhelmingly approved the Ryan-Murray plan just two days after it was introduced.

But now, the Pentagon has once more gotten a reprieve from the budget ax: Under Murray and Ryan’s congressional budget deal, the Pentagon will get an additional $32 billion, or 4.4 percent, in 2014, leaving its base budget at a higher level than in 2005 and 2006. (The Department of Defense expects its total 2014 budget, including supplemental war funding, to be more than $600 billion.)

Before the budget deal, some critics of defense spending had been ready to accept sequestration as the blunt, imperfect tool that might force the military to shed some of the bulk it acquired while fighting two of the longest and most expensive wars in our history. Even with the sequester in place, the Pentagon’s base budget was set to remain well above pre-9/11 levels for the next decade, and the military would have taken a far smaller haircut than it did after Vietnam and the Cold War wound down.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan cost $1.5 trillion, about twice the cost of the Vietnam War when adjusted for inflation. Those funds came entirely from borrowing, contributing nearly 20 percent to the national debt accrued between 2001 and 2012. And that’s just the “supplemental” military spending passed by Congress for the wars—the regular Pentagon budget also grew nearly 45 percent between 2001 and 2010.

No wonder, perhaps, that defense watchdogs found the Pentagon’s wailing about the sequester less than convincing. “These ‘terrible’ cuts would return us to historically high levels of spending,” snapped Winslow Wheeler of the Project on Government Oversight. According to Lawrence J. Korb, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, the Pentagon could reduce its budget by $100 billion a year without undermining its readiness. The sequestration cuts for 2013 amounted to $37 billion.

Not so long ago, a hawkish GOP politician called for the “bloated” defense establishment to “be pared down” and retooled for the 21st century. The new budget deal doesn’t reissue the blank check the Pentagon received during the past decade, but it may have removed the incentive to pare down. Below, a field guide to just how big the Pentagon budget is—and why it’s so hard to trim. (That GOP politician? Former Sen. Chuck Hagel, now the secretary of defense.)

Our military is mind-bogglingly big.

- The Pentagon employs 3 million people, 800,000 more than Walmart.

- The Pentagon’s 2012 budget was 47 percent bigger than Walmart’s.

- Serving 9.6 million people, the Pentagon and Veterans Administration together constitute the nation’s largest healthcare provider.

- 70 percent of the value of the federal government’s $1.8 trillion in property, land, and equipment belongs to the Pentagon.

- Los Angeles could fit into the land managed by the Pentagon 93 times. The Army uses more than twice as much building space as all the offices in New York City.

- The Pentagon holds more than 80 percent of the federal government’s inventories, including $6.8 billion of excess, obsolete, or unserviceable stuff.

- The Pentagon operates more than more than 170 golf courses worldwide.

One out of every five tax dollars is spent on defense.

The $3.7 trillion federal budget breaks down into mandatory spending—benefits guaranteed the American people, such as Social Security and Medicare—and discretionary spending—programs that, at least in theory, can be cut. In 2013, more than half of all discretionary spending (and one-fifth of total spending) went to defense, including the Pentagon, veterans’ benefits, and the nuclear weapons arsenal.

We’re still the world’s 800-pound gorilla.

When it comes to defense spending, no country can compete directly with the United States, which spends more than the next 10 countries combined—including potential rivals Russia and China, as well as allies such as England, Japan, and France. Altogether, the Pentagon accounts for nearly 40 percent of global military spending. In 2012, 4.4 percent of our GDP went to defense. That’s in line with how much Russia spends; China spends 2 percent of its GDP on its military.

Too big to audit

Where does the Pentagon’s money go? The exact answer is a mystery. That’s because the Pentagon’s books are a complete mess. They’re so bad that they can’t even be officially inspected, despite a 1997 requirement that federal agencies submit to annual audits—just like every other business or organization.

The Defense Department is one of just two agencies (Homeland Security is the other) that are keeping the bean counters waiting: As the Government Accountability Office dryly notes, the Pentagon has “serious financial management problems” that make its financial statements “inauditable.” Pentagon financial operations occupy one-fifth of the GAO’s list of federal programs with a high risk of waste, fraud, or inefficiency.

Critics also contend that the Pentagon cooks its books by using unorthodox accounting methods that make its budgetary needs seem more urgent. The agency insists it will “achieve audit readiness” by 2017.

Anatomy of a budget buster

In the early 2000s, the Pentagon began developing a new generation of stealthy, high-tech fighter jets that were supposed to do everything from landing on aircraft carriers and taking off vertically to dogfighting and dropping bombs. The result is the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, whose three models (one each for the Navy, Air Force, and Marines) are years behind schedule, hugely over budget, and plagued with problems that have earned them a reputation as the biggest defense boondoggle in history.

- Rolling out the F-35 originally was expected to cost $233 billion, but now it’s expected to cost nearly $400 billion. The time needed to develop the plane has gone from 10 years to 18.

- Lockheed says the final cost per plane will be about $75 million. However, according to the Government Accountability Office, the actual cost has jumped to $137 million.

- It was initially estimated that it could cost another $1 trillion or more to keep the new F-35s flying for 30 years. Pentagon officials called this “unaffordable”—and now say it will cost only $857 million. “This is no longer the trillion-dollar [aircraft],” boasts a Lockheed Martin executive.

- Planes started rolling off the assembly line before development and testing were finished, which could result in $8 billion worth of retrofits.

- A 2013 report by the Pentagon inspector general identified 719 problems with the F-35 program. Some of the issues with the first batch of planes delivered to the Marines:

- Pilots are not allowed to fly these test planes at night, within 25 miles of lightning, faster than the speed of sound, or with real or simulated weapons.

- Pilots say cockpit visibility is worse than in existing fighters.

- Special high-tech helmets have “frequent problems” and are “badly performing.”

- Takeoffs may be postponed when the temperature is below 60°F.

- The F-35 program has 1,400 suppliers in 46 states. Lockheed Martin gave money to 425 members of Congress in 2012 and has spent $159 million on lobbying since 2000.

Ways to save a few billion

There are savings to be had within the Pentagon’s massive budget—if politicians can weather the storm that kicks up whenever a pet project is targeted. Here are 10 ideas for major cuts from an array of defense wonks, from the libertarian Cato Institute and the liberal Center for American Progress to the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

| Proposal | Estimated savings |

|---|---|

| Get rid of all ICMBs and nuclear bombers (but keep nuclear-armed subs). | $20 billion/year |

| Retire 2 of the Navy’s 11 aircraft carrier groups. | $50 billion through 2020 |

| Cut the size of the Army and Marines to pre-9/11 levels. | At least $80 billion over 10 years |

| Slow down or cancel the pricey F-35 fighter jet program. | At least $4 billion/year |

| Downsize military headquarters that grew after 9/11. | $8 billion/year |

| Cancel the troubled V-22 Osprey tiltrotor and use helicopters instead. | At least $1.2 billion |

| Modify supplemental Medicare benefits for veterans. | $40 billion over 10 years |

| Scale back purchases of littoral combat ships. | $2 billion in 2013 |

| Cap spending on military contractors below 2012 levels. | $2.9 billion/year |

| Retire the Cold War-era B-1 bomber. | $3.7 billion over 5 years |

Why Congress spared the Pentagon

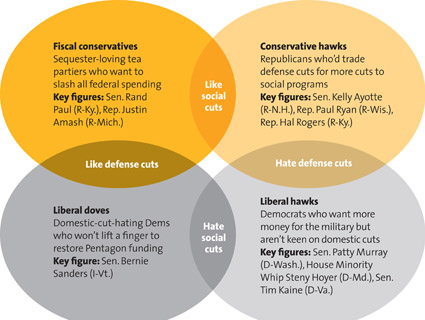

A few weeks ago, an agreement to end the cycle of budget crises and fiscal hostage-taking seemed distant. Sequestration had few friends on the Hill, but the parties could not agree on how to ditch the automatic budget cuts to defense and domestic spending. Republicans had proposed increasing defense spending while taking more money from Obamacare and other social programs, while Democrats said they’d scale back the defense cuts in exchange for additional tax revenue. Those ideas were nonstarters: Following the government shutdown in October, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) called the idea of trading Social Security cuts for bigger defense budgets “stupid.”

Which explains why Rep. Ryan and Sen. Murray’s deal craftily dodged taxes and entitlements while focusing on the one thing most Republicans and Democrats could agree upon: saving the Pentagon budget. This chart shows why military spending is the glue holding the budget deal together.

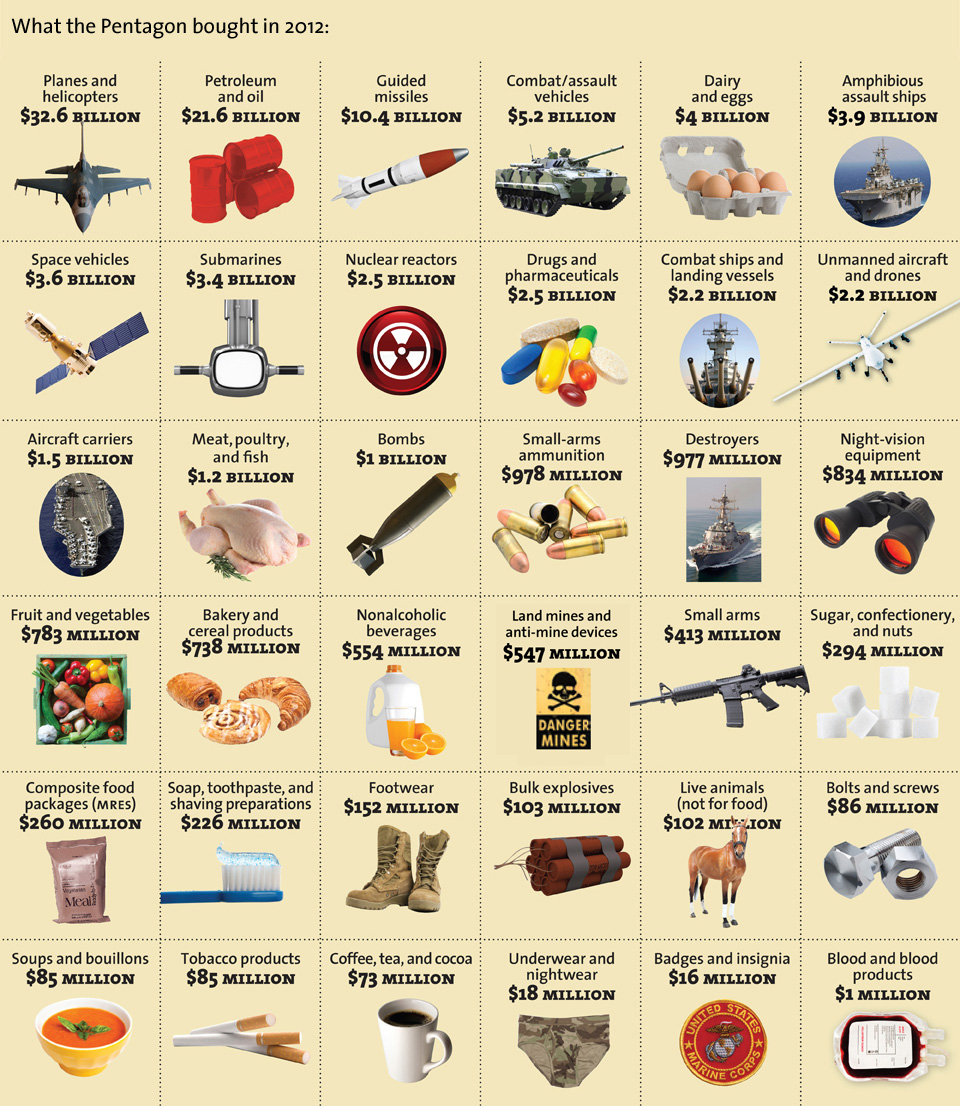

Guns and butter

A closer look at the $361 billion handed to military contractors in 2012 reveals the enormous amount of stuff the modern military consumes. Some of the items on the shopping list: