Matt Chase

UPDATE 6/25/15 10:10 a.m.: The Supreme Court just ruled in a 6-3 decision to uphold Obamacare’s subsidies, rejecting the case of the King v. Burwell plaintiffs.

When I saw the white stretch limousine parked out front, I knew I’d found the right place. I walked down the gravel driveway toward the white single-level house with trepidation; the owner’s Facebook page had suggested the possibility of pit bulls. But I was greeted at the door by David King, a garrulous 64-year-old self-employed limo driver who has lent his name to what may be the weightiest case to come before the Supreme Court in years. I’d come unannounced to King’s modest home in Fredericksburg, Virginia, to learn why he’d agreed to headline a legal assault that, if successful, could hobble the Affordable Care Act and result in millions of Americans losing their health insurance.

Asked what he might get out of King v. Burwell, the burly, mustachioed Vietnam vet replied that the only benefit he anticipated was the satisfaction of smashing the signature achievement of the president he loathes. Obamacare, King explains, bilks hardworking taxpayers to support welfare recipients. Those people who might end up without insurance? He didn’t care, because “they’re probably not paying for it anyway.”

Of course, you can’t challenge a law simply because you hate it. Legally, King’s case rests on his claim that he has been personally harmed by the law, specifically its subsidies to help people buy health insurance. He alleges that the subsidies are illegal in states without insurance exchanges and put him in a position where he must get health insurance or pay a penalty.

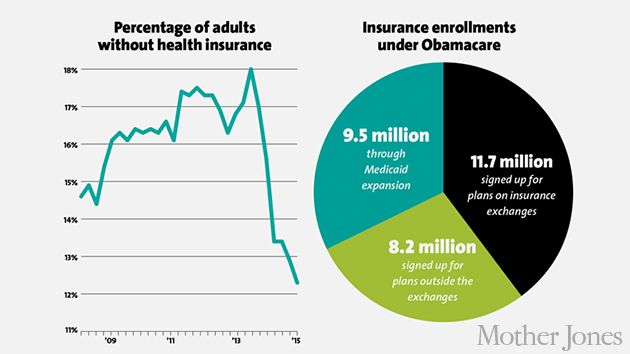

If five Supreme Court justices buy this argument, the stakes are huge: More than 13 million people could lose their subsidies and about 8 million could lose their health insurance altogether. Public health experts estimate that nearly 10,000 of them could die every year as a result. Premiums for some plans could skyrocket by as much as 256 percent. The insurance markets in more than 30 states could implode.

The case is the work of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank funded by pharmaceutical firms, the Koch brothers, and Google, among others. While the legal logic behind the suit is obtuse (much of it hinges on what one appeals judge called “a tortured, nonsensical” interpretation of two sentences in the law), its goal is simple: As the center’s then-chairman declared in 2010, Obamacare “has to be killed as a matter of political hygiene.”

But first CEI had to recruit real people who could claim they had been harmed by the Affordable Care Act. That led them to King and his three fellow plaintiffs, one man and two women. The four had been largely absent from coverage of the lawsuit, but after the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case this spring, I set out to find out just how Obamacare would hurt them.

King’s situation was typical of what I found. He wouldn’t say whether he currently had health coverage, but he was adamant that he would never take advantage of Obamacare, no matter what. Last year, according to court filings, his income was $39,000. With an Obamacare subsidy, he could have purchased a health plan for as little as $275 a month (or less, if he weren’t a smoker). Without the subsidy, the same plan would cost $648 a month. Most importantly, for purposes of the case, King wasn’t actually required to buy coverage at all: Under the law, he qualifies for a financial hardship exemption because the cost of subsidized insurance is more than 8 percent of his income.

Plaintiff No. 2 was Brenda Levy, a 64-year-old substitute teacher who lives outside of Richmond, Virginia. With her wild, frizzy hair and earthy clothes, Levy looks like an aging hippie. When I met her at her log-cabin-style house, she mentioned that she’d once belonged to the Sierra Club and used to read Mother Jones. Levy insisted she leads “a quiet life,” but she is politically active. She’s donated to conservative causes and has been involved in opposing gay rights. In 2013, she helped organize a rally to protest the Boy Scouts’ plan to admit gay kids.

Surprisingly, she didn’t recall exactly how she had been selected as a plaintiff in the case. “I’m gonna have to ask them how they found me,” she said. When I talked to her in January, more than a year after the case was filed, she’d still never met the lawyers handling it. Asked if she realized that her lawsuit could potentially wipe out health coverage for millions, she looked befuddled. “I don’t want things to be more difficult for people,” she said. “I don’t like the idea of throwing people off their health insurance.” She was under the impression that expanding Medicaid might help anyone who lost their insurance—unaware that Medicaid expansion was actually part of Obamacare, or that the same groups backing her lawsuit have opposed this expansion in her state.

Levy claimed Obamacare gives the government control over Americans’ medical treatment and had caused insurance premiums to rise. She told me her monthly premiums, purchased outside the exchange, were more than $1,500, which she attributed to health woes, including two hip replacements and two craniotomies. “I’ve had some holes drilled in my head,” she quipped. Levy hadn’t checked out the plans she qualifies for under Obamacare, but an affidavit filed by the government in King v. Burwell indicates that she could have purchased a low-cost plan on the federal exchange for $149 a month.

Tracking down the third plaintiff wasn’t so easy. The home address 56-year-old Rose Luck had provided in legal filings turned out to be an extended-stay motel on a commercial strip in Petersburg, Virginia. When I finally reached her by phone, Luck hung up on me. Contacted via Facebook, she responded, “Please leave me alone.” But social media and public records provide a snapshot of her life. On her Facebook page, she has called Obama the “anti-Christ” and voiced her belief that he came to power because “he got his Muslim people to vote for him.” She has warned that Obamacare will cost people $77,000 a year.

Since the late 1990s, Luck and her husband have faced legal judgments for nearly $5,000 in unpaid medical bills, something that typically happens to people with inadequate or no insurance. (The judgments have since been paid off.) Luck’s Facebook page also made clear that she had experienced serious health problems, raising questions about her insistence that she would prefer to go uninsured or buy high-deductible catastrophic coverage. According to government filings, the cheapest plan available to her on the exchange would cost $333 per month. And like King, she is eligible for a hardship waiver.

The final plaintiff was Doug Hurst, another Virginian in his early 60s. According to bankruptcy filings, Hurst and his wife had more than $8,500 in out-of-pocket medical expenses in 2009. His insurance premiums in 2010 were $655 a month. Under Obamacare, Hurst could have purchased a bronze health plan for $62 a month. I never spoke with him, but I reached his wife, Pam, on the phone. She declined to talk about the case or her family’s experiences with the health care system. (In 2009, her 37-year-old daughter died following a long struggle with schizoaffective disorder.) She told me angrily, “I’m very well aware of my situation. You are not. You are not aware of extenuating circumstances. I don’t have to justify my life, the loss of my child, which included the loss of a business, to anyone, do you understand?”

The weakness of the King plaintiffs’ individual claims of injury—particularly given the fact that Obamacare would likely help, not hurt, them—suggests that it wasn’t easy to find people to join CEI’s lawsuit. When I mentioned this to Michael Carvin, the plaintiffs’ lead lawyer, he bristled. “Linda Brown was the only plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education,” he retorted, invoking the Supreme Court case that led to school desegregation. “Does that suggest there weren’t a lot of people who supported her point of view?” (In fact, Linda Brown’s father was one of 13 original plaintiffs in that case, which was filed as a class action.)

During the oral arguments before the Supreme Court in March, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg quizzed Carvin about whether his clients actually had the legal standing to bring the case. “At least one plaintiff has to have a concrete stake in these questions,” she said. “They can’t put them as ideological questions.” Carvin responded that the lower courts had accepted his clients’ qualifications. Ginsburg wasn’t deterred from probing further. “The court has an obligation to look into it on its own,” she said.