Eric Gay/AP

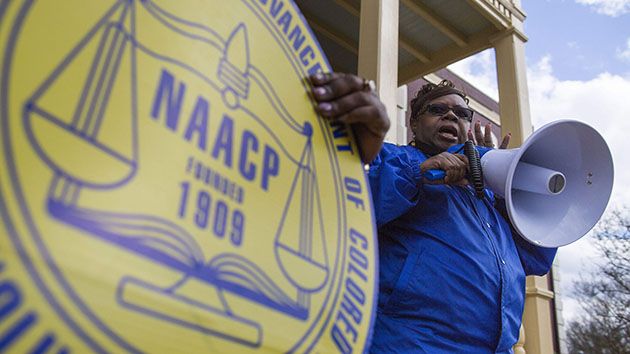

Voting rights advocates, the Department of Justice, and a string of other plaintiffs enjoyed a rare victory this week when a federal appeals court ruled that Texas’ voter ID law, one of the strictest in the nation, disproportionately hurts minority voters, and ordered interim relief in time for the November elections. This win did not come easily. According to Gerry Hebert, executive director of the national Campaign Legal Center and a lawyer for the lead plaintiffs, the law’s opponents had to raise more than $1 million to litigate the case.

“The million dollars that we had to raise had to be shouldered by the victims of discrimination,” Hebert said.

Just three years ago, these efforts would not have been necessary, because a crucial element of the 1965 Voting Rights Act was still in place. In 2012 the Texas voter ID law was blocked by a federal court in Washington, DC, which under Section 5 of the VRA was charged with reviewing changes to voting laws in states such as Texas, Alabama, and seven others with histories of discrimination. The court ruled that the Texas law, known as SB 14, would likely result in a “retrogression in the position of racial minorities” in the electoral process. But the following year, a Supreme Court ruling in Shelby County v. Holder effectively voided Section 5. That same day, Texas began enforcing its voter ID law.

The loss of Section 5 came as a blow to the voting rights movement. “It was our most effective way to stop racial discrimination in voting,” said Julie Fernandez, advocacy director for voting rights at the Open Society Foundations. Previously, the courts could rule on a law’s potentially discriminatory effect before it was even implemented; now, that could only happen after the fact and on the backs of plaintiffs. “The beauty before Shelby County was that the burden was not on the victims of discrimination,” Hebert said, “it was on the perpetrators of discrimination.”

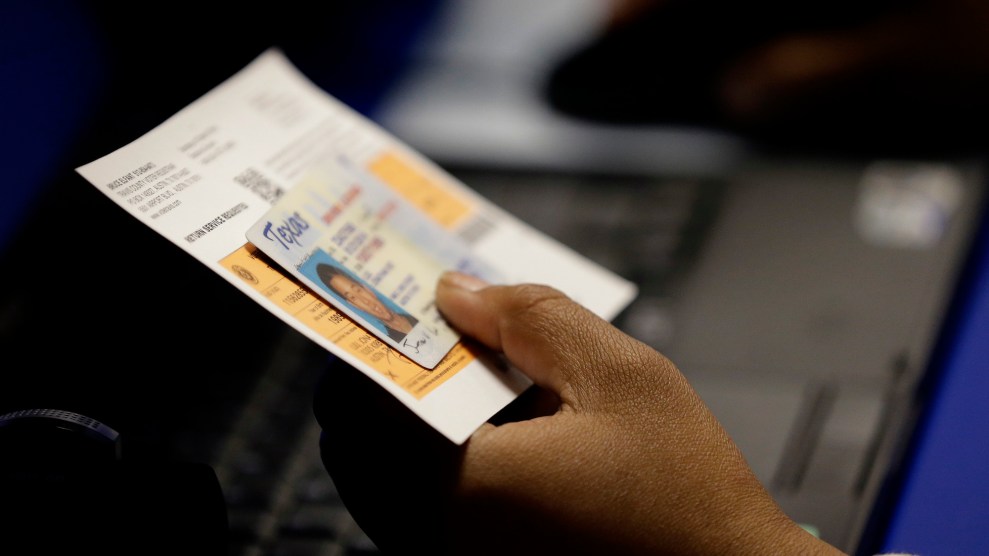

In Texas, SB 14 had an immediate impact. A district court found in 2014 that more than 600,000 Texas voters lacked the necessary ID to vote under the law; for a variety of reasons, some of which are laid out in a video produced by the Campaign Legal Center, many Texans faced barriers to acquire the IDs.

Proposals for voter ID laws appeared repeatedly in the Texas Legislature in the late 2000s, but no bill advanced to the floor of the state Senate for several years because of an old custom that required a two-thirds majority to agree to hold a vote at all. By 2011, there was a concerted push to get a bill through, the two-thirds requirement was suspended, procedural barriers that might have slowed the process were removed, and SB 14 sailed through the Legislature. “Such treatment was virtually unprecedented,” the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, the most conservative of all the circuits, wrote in its ruling.

It’s unclear why Texas legislators decided at that moment that a voter ID law was necessary; only two people had been convicted for in-person voting fraud “out of 20 million votes cast in the decade leading up to SB 14’s passage,” noted the appeals court. Nina Perales, an attorney with the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, recalls a sudden surge in Texans’ concerns about immigration and the purported risk of illegal immigrants casting fraudulent votes. “Everything collapsed into a giant immigration-voter-fraud Latino demographic issue,” she said.

In arguing whether the bill was discriminatory, both a federal district judge in 2014 and the appeals court this week pointed to the fact that amendments proposed before its passage that might have attenuated the law’s impact on minorities were not adopted. The appeals court’s opinion states that proponents “were aware of the likely disproportionate effect of the law on minorities, and that they nonetheless passed the bill.” The appeals court ruled only that the law was discriminatory in effect; the question of whether it was discriminatory in intent, as a lower court had held, has been remanded for further consideration.

SB 14 was considered discriminatory not because it required voters to present identification but because of its restrictions on the kinds of identification that were needed to vote. “They didn’t allow student IDs from public universities, they didn’t allow federal employee IDs, they didn’t allow state employee IDs,” Hebert from the Campaign Legal Center said. The IDs that were allowed, he said, were those “disproportionately held by whites.”

Texas could now appeal to the Supreme Court, although with the death of conservative Justice Antonin Scalia earlier this year, the state’s chances for a victory in the high court may have fallen. But whatever comes next for the Texas case, the plaintiffs’ yearslong, million-dollar fight against SB 14 represents a new norm in the battle over voting rights. Without federal oversight, it is now up to civil society organizations to monitor the bills working their way through statehouses around the country and to fund suits against questionable laws.

“There are things that are being done now by state and local governments that would have been blocked before Shelby County,” Hebert said. “Things they would have never been allowed to do before…And we have to sue them over it, which costs money, time, and it’s quite a burden.”

Additional reporting by Project Turnout.