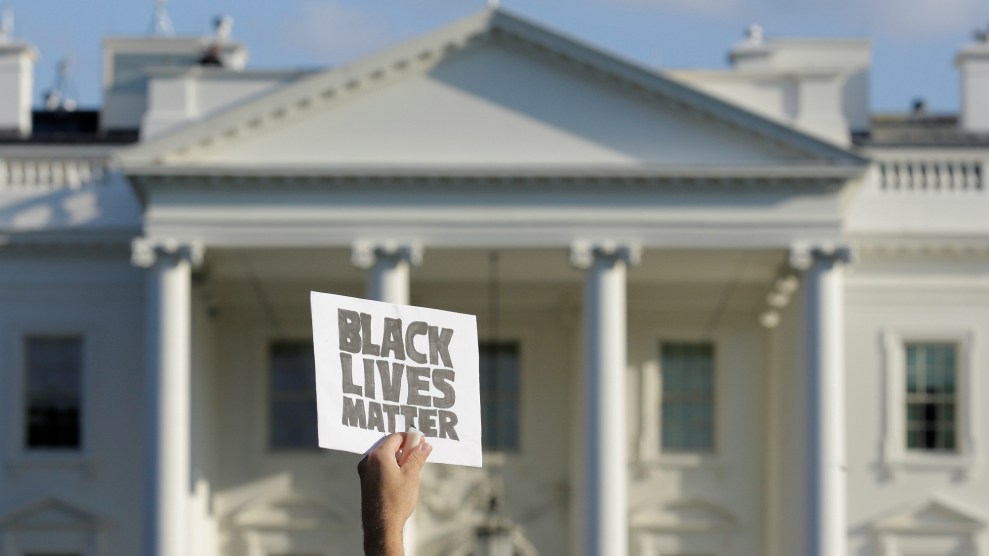

Joshua Roberts/Reuters via ZUMA Press

In the ongoing and sometimes tortuous evolution of Black Lives Matter, from a statement to a movement, from a protest to a call for action, Wednesday marks the day the loose coalition of activists takes on a new role: lobbying Congress.

A group of activists will convene on Capitol Hill on Wednesday to push lawmakers to strengthen a criminal sentencing reform bill and share its vision for racial justice. The activists, from the National Black Justice Coalition and the Black Youth Project 100, will present the members of Congress with a six-point policy platform, known as A Vision for Black Lives, released in August by the Movement for Black Lives, a collective of racial justice groups and individuals working under the Black Lives Matter umbrella.

“What we wanted was to make sure that [our] vision was articulated so people could not say we don’t know what we want,” says M. Adams, a member of the Movement for Black Lives leadership team.

The platform and Wednesday’s lobbying effort, billed as the Build Black Futures Advocacy Day, highlight both the movement’s decision to work more directly with the political process and its fundamental challenge in reaching consensus to advance the significantly divergent viewpoints of its members. The platform moves far beyond the movement’s founding issue of police violence against African Americans, pressing for change on matters such as gay and transgender rights. And the lobbying comes in spite of the movement’s ingrained skepticism of politics and politicians.

“If they were committing to do it on their own they would have already done it,” says Adams, who is not involved in Wednesday’s lobbying effort. “There is an on-the-ground movement, [we believe that] change comes from the bottom up. We don’t think that politicians will all of a sudden work with us and create the fundamental change that we are seeking.”

The sentencing reform bill, which has the support of a bipartisan group of politicians and the White House, calls for a reduction in many drug sentences. But activists have expressed concerns that the bill, with its addition of new mandatory minimums in some cases, does not provide sufficient reforms to a system that has had a disproportionate impact on racial minorities.

“We’re very pleased that criminal justice reform is being talked about on Capitol Hill,” says Isaiah Wilson of the National Black Justice Coalition, a civil rights group that focuses on federal policy. “But we want to make sure that the [black] community is being addressed in this conversation.”

The Movement for Black Lives was born of the organizing that began in Ferguson, Missouri, after the 2014 death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager killed during an encounter with a police officer, and the militarized law enforcement response to the protests. Last summer, more than 1,000 black activists descended on the campus of Cleveland State University for the Movement for Black Lives Convening, a three-day conference where organizers from across the country gathered to discuss the fight for racial justice. After the conference, activists and grassroots organizations continued to work together as a collective, a relationship that eventually led to the creation of the Vision for Black Lives platform.

Crafted over the course of the past year, the document has six core demands: an end to the “war on black people”; reparations for black victims of “past and continuing harms”; divestment from institutions that harm black people and investment in institutions that support them; economic justice; community control of local institutions; and independent black political power. Several dozen grassroots organizations, as well as national policy groups and activists across the country, weighed in on its creation, and it was informed by the work of black activists from previous generations, including the Ten-Point Program of the Black Panther Party in 1966 and the Freedom Agenda of the Black Radical Congress in 1999. That’s why, although “the media has focused on police killings,” says Chinyere Tutashinda of the Center for Media Justice, one of the organizations involved in the platform’s development, the platform encompasses a broader array of issues.

African Americans have been a reliably Democratic voting bloc for decades, but their voting power has grown considerably in the past two presidential elections’ cycles. The historic gap between voter turnout among blacks and whites has all but disappeared, with black turnout surpassing white turnout in the 2012 presidential election for the first time in recorded electoral history.

But the increased power of black voters has not necessarily resulted in favorable policy outcomes. Instead, political scientists say, black voters’ consistent support for the Democratic Party may have turned them into a “captured” demographic—a group that is so overwhelmingly in favor of one party that their issues are overlooked by both sides during elections. Research has found that the more support a policy has from black voters, the less likely it is to become law.

The Vision for Black Lives platform argues that building “independent black political power” and self-determination would empower marginalized people to speak for themselves. Jodeen Olguín-Tayler of Demos, a policy think tank that consulted with the activists during the drafting of the platform, says that acting on the policies outlined within the platform is one way for politicians to show they are invested in the well-being of black communities.

With its day of action on Capitol Hill, the Movement for Black Lives has shown that it’s invested in politics as well. But even if Congress doesn’t act, activists say they will continue to push for change. “Our communities are committed to justice,” says Adams. “There will be engagement with those in power, and it’s going to be on our terms.”