I was doomscrolling again. It was a fall evening in 2023, and I found myself sucked into a stream of posts about our collapsing climate: droughts causing billions in Dust Bowl–style crop damage, Florida’s worst-ever coral bleaching, a record melt in Greenland.

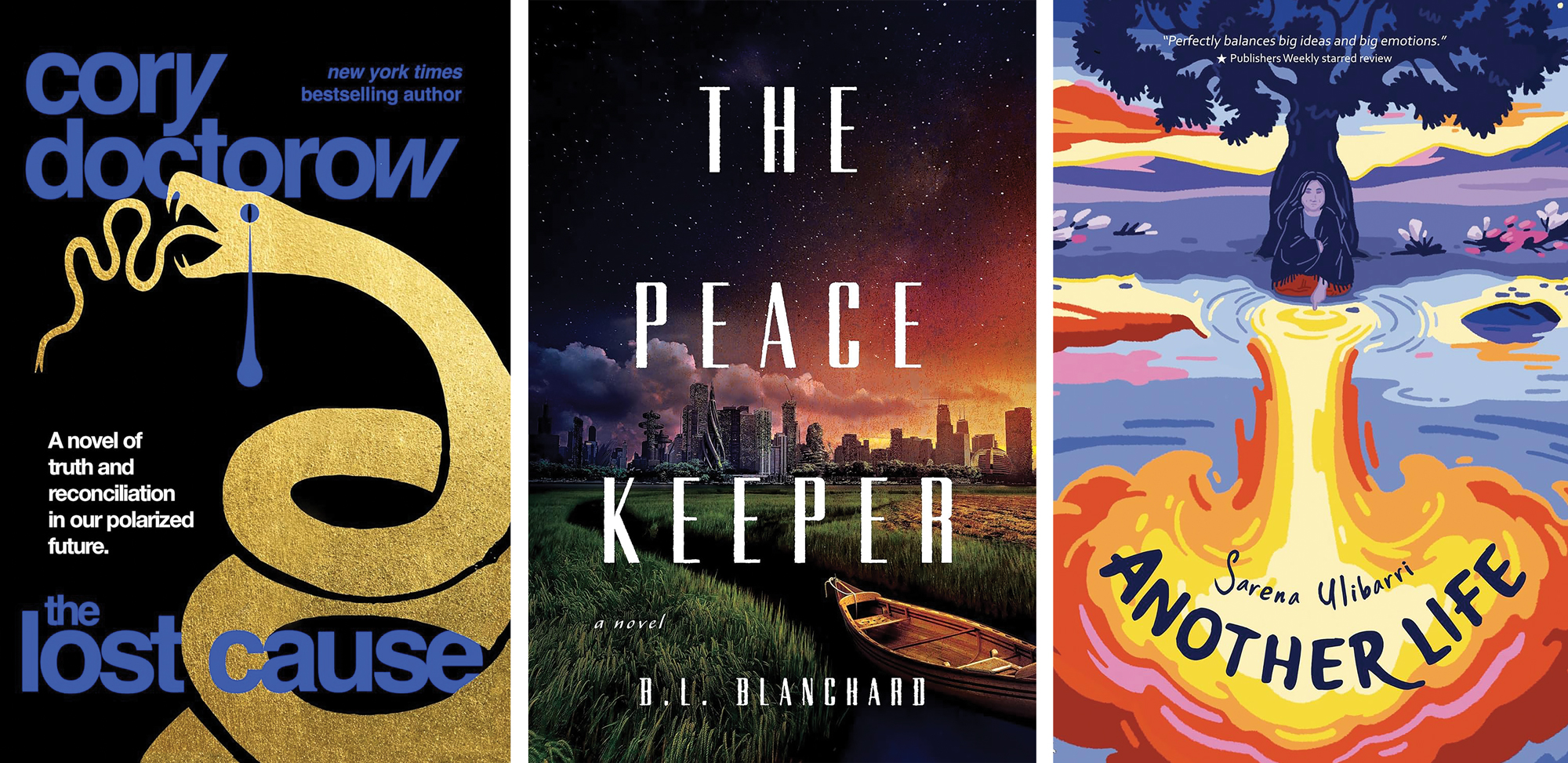

To distract myself, I picked up The Lost Cause, the latest sci-fi novel from author Cory Doctorow, a friend and fellow nerd. To my deep surprise, it stirred something unexpected: a feeling of hope.

At first glance, the novel’s backdrop is an absolute bummer. It takes place in America several decades from now, when rising seas have destroyed entire coastal towns and millions of climate refugees wander around homeless. Small farmers work as sharecroppers for Big Agriculture. The West is choked with forest fires so ferocious that Californians take hits from oxygen cans.

And yet, clean tech has gotten remarkably better. Solar panels are so cheap and powerful that they can be used to heat concrete kilns and build entire buildings carbon-neutrally. A progressive president’s Green New Deal guarantees universal employment, including jobs relocating entire coastal cities inland, away from the rising, voracious oceans. The heroes—SoCal resident Brooks and his twentysomething friends—spend their days doing on-demand work (solarizing schools, building high-density housing) and chill out at night, drinking artificial bourbon they brew in a bioreactor. While clean energy is abundant, so is political strife: MAGA-esque forces, armed to the teeth, violently oppose waves of climate “refus” arriving from fire-wrecked Oregon. When Brooks and his crew decide to build refugee housing anyway, their clash with right-wing old-timers gets nasty and violent fast—complete with cross burnings.

If you want to nudge people toward a better tomorrow, start with art.

So, not exactly a utopia. But what enchanted me about the book was its vibe of possibility. Here was a world where climate change had gotten worse, but people were adapting—cleverly using tech to rebuild communities that would generate far fewer emissions and far less waste than before. It was a glimpse of a new destination.

Sci-fi has always offered this, right? Heady alternatives to everyday realities! But for the past few decades, a big chunk of sci-fi had gravitated toward dystopia. The “cyberpunk” movement imagined technology and capitalism run amok—overcrowded, skyscrapered cities; enervated populations jacking into virtual reality realms; governments sidelined or incinerated. There were some notable exceptions: Novelists Kim Stanley Robinson and Ursula K. Le Guin, for example, imagined people living in closer harmony with nature or in worlds without capitalism. But they were outliers. The aughts, which brought us a second Iraq War, the Great Recession, and increasingly volatile natural disasters, also set the scene for astoundingly bleak bestselling young-adult series such as The Hunger Games, Divergent, and The Maze Runner. Winter was coming, and as far as many sci-fi writers could prognosticate, humanity was unlikely to rise to the challenge.

Dystopic tales of the future can be valuable, showing us what might happen if we let malignant trends go unchecked. But for me, man, those warnings have long since sunk in. I wanted pointers to a path forward. Which is why I’ve become so intrigued with solarpunk.

Doctorow’s book is part of a sci-fi trend that’s gained traction in recent years, picking up on the threads Le Guin and Robinson laid down. Solarpunk poses a fascinating question: What would a world that had seriously tackled climate change look like?

Many solarpunk thinkers told me their first encounter with the idea, though he didn’t coin the term, was a 2014 essay by Adam Flynn, an American writer and public health strategist, titled “Solarpunk: Notes toward a manifesto”—his contribution to the Arizona State University sci-fi collaboration Project Hieroglyph.

“We’re solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair,” Flynn wrote. Artists and activists needed to envision “ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and more importantly for the generations that follow us…Imagine permaculturists thinking in cathedral time. Consider terraced irrigation systems that also act as fluidic computers. Contemplate the life of a Department of Reclamation officer managing a sparsely populated American southwest given over to solar collection and pump storage.”

Other writers were, it turns out, having similar thoughts. They were deeply worried about climate and weary of sci-fi’s doomerist turn. They wanted art that elucidated a way forward, so they set about creating fictional glimpses of a sustainable future. In a duet of novels, Becky Chambers sketched out a world where humanity had survived climactic collapse—the robots became self-aware and politely fled into the wilderness—and then figured out how to exist in a better balance with nature: Her characters live in skyscrapers engulfed with vines, ride e-bike camper vans powered by solar panel coatings, and have abandoned swaths of their world to the wild.

In Sarena Ulibarri’s 2023 novel Another Life, a communal society runs solar desalination plants that irrigate Death Valley. The 2018 Brazilian short-story anthology Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World includes a classic hard-bitten-detective whodunit set in a world where homes have biodigesters that turn kitchen scraps into fuel.

Solarpunk often depicts technology deployed not to conquer nature, but to complement it—sometimes in deeply weird ways. In the story “Thank Geo,” whose author goes by the moniker BrightFlame, humanity has wired trees with probes that let people talk to them.

The solarpunk community’s interests extend beyond literature, though. Some of the greatest ferment is online, where everyday folks cram into themed subreddits, Tumblrs, and Substacks, posting their mood-board images of a better future. Some of it is fantasy—solar airships with grappling hooks hovering over vertical farms—but more often, the posts involve solarpunkish things already happening: people planting guerrilla wetlands in aqueducts, solar-powered root cellars, “agrivoltaic” farms where sheep graze beneath industrial photovoltaic arrays. Broadly speaking, as Ulibarri put it to me, solarpunk depicts “a future that I might actually want to live in.”

Solarpunk characters are flawed, despite the genre’s optimism: “As a society, we have not become suddenly worthy of utopia.”

I have often assumed, naively, that societal transformation depends on explicitly political discourse. People write manifestos and policy papers, and political movements and parties build on and promote those ideas. But the world of solarpunk operates on the same understanding that propels Steve Bannon: Politics is downstream of culture. If you want to nudge people toward a better tomorrow, start with art. The point, said Jay Springett, a writer who co-manages a popular solarpunk Tumblr, is to give people “permission to imagine a future.”

Another way of thinking about it, Doctorow told me, is to follow philosopher Daniel Dennett’s argument that “fiction is an intuition pump.” When reading a novel, Doctorow explained, you might “kind of mentally rehearse what you should do when bad things happen, so in that moment you’re not paralyzed—like a fire drill.”

A lot of apocalyptic literature would prime us with terrible intuition: how to survive in a Hobbesian everyone-for-themselves scenario of neighbor slaughtering neighbor for scarce fuel and food. Novels like The Lost Cause bolster a competing notion: that surviving and thriving in the face of climate-driven disruption happens only if people band together and rely on sustainable technologies.

One intriguing aspect of solarpunk culture is that it feels proximal—achievable. The tech is scaled up, but much of it involves innovations we possess now, like solar panels, wind turbines, 3D printers, passive cooling systems, and recycling (on steroids). “One of the key tenets of solarpunk is that you don’t need to wait for new technology,” explained novelist and teacher Cameron Roberson. We don’t need unobtainium or warp drives—just political will.

Indeed, solarpunk often depicts societies and groups that have strayed from capitalism—or hierarchical governments of any sort. Decision-making is often racked with the bitter internecine squabbles for which nonhierarchical groups are infamous. But things work…more or less? Doctorow jokes that part of the thought experiment in The Lost Cause is: “What would it be like to have a space program or a skyscraper that you made like you made Wikipedia? It would have all the fights; it would have all the frustrations—but also, it would be a skyscraper!”

This anti-capitalist turn is probably the most speculative aspect of solarpunk. A popular adage is that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Solarpunk flips that on its head: If you’re going to imagine the world not ending, maybe you need to imagine a new economic system.

At its weakest, solarpunk can get treacly, with societies too well adjusted to seem believable and denizens as amiable as Winnie-the-Pooh. The most interesting stories, to me, are ones in which we tackle climate change but are still terrible to one another. In 2022’s The Peacekeeper, Chippewa novelist B.L. Blanchard imagines a contemporary North America that was never colonized. Native populations have all the mod cons—smartphones, etc.—but are still so nature-oriented that they lean hard into clean tech. Emissionless public transit abounds and huge mirrors along the Great Lakes reflect sunlight onto massive solar panels. But their world isn’t free of misdeed; The Peacekeeper is a murder mystery, complete with a tormented detective.

As novelist Roberson puts it, we can save the world and still lose ourselves. In his forthcoming novel, a noir tale, the tech is clean and the souls are dirty. “Government is still government, people are still people, criminals are still criminals,” he told me. “As a society, we have not become suddenly worthy of utopia.”

Solarpunk, by now, has adopted some weary sci-fi cliches and added a few of its own. Domed cities! Grandpa explaining to the grandkids how everything fell apart! 3D printers that seem to be able to manufacture, well, anything! Even real-world corporations have picked up on the subgenre’s gauzy imagery. Yogurt-maker Chobani released an animated commercial in 2021 depicting a farm serviced by moss-covered androids and pole-mounted raincloud generators. Solarpunk forums argued hotly about whether this was a) corporate greenwashing; b) a sign that their vision could appeal to a wider public; or, more likely, c) both.

There are political crossovers, too. On an Instagram Live in 2023, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said she was a big believer in solarpunk—the yet-unsuccessful Green New Deal package she championed did, in fact, contain the very blend of energy policies and economic reforms (job guarantees, universal health care, progressive taxation) that solarpunks fantasize about.

“To go, in less than 10 years, from Tumblr, where you and I found it, to having people in the halls of power endorse your cultural project, that’s pretty good,” said Andrew Dana Hudson, who penned a series of solarpunk stories. “We built an entire cultural architectural aesthetic around powering things with gasoline and coal,” he added. Now artists and writers need to make the alternative just as sexy and appealing.

The time seems ripe. Theodra Bane, a professor at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, has taught a solarpunk class for three years now. Far more students apply to get in than she can accommodate. Roughly a third, Bane said, will say something along the lines of, “I don’t know what solarpunk is, but the course description led me to believe that it is a positive, optimistic class—and I need optimism right now.”