Photo collage: <a href="/authors/tim-luddy">Tim J Luddy</a>; Flag: Roel Smart/iStockphoto

Ian Freeman’s campaign of civil disobedience started on the autumn day in 2008 when the Blue Light Gang came for his couch. It was a plaid three-seater, anonymous even by the standards of living-room furniture, except that it occupied prime real estate on the front lawn of his two-story, white-and-green renter in Keene, New Hampshire. His tenants used it for bird-watching. But in this quiet college town near the Vermont border, that put him on the wrong side of a city ordinance that considers such exterior furnishings “rubbish.” A neighbor lodged a complaint. Code enforcement—the Blue Light Gang, as Freeman calls them—asked him to get rid of the couch. He refused. A man has to stand for something.

In court, Freeman (whose given surname is Bernard) represented himself and grilled the lone witness, a city code enforcer. He refused to plead guilty—or not guilty, for that matter—and instead asked the city to pay him a $5,000-per-hour appearance fee (PDF); otherwise he’d consider it kidnapping. The court was not amused. What started as a fine for littering (PDF) escalated to a 90-day jail sentence for three counts of contempt plus an additional three days for violating the rubbish rules. (Freeman ultimately served four days.)

In recent years, Keene residents have been cited for violating the city’s open-container law (during a city council meeting), for indecent exposure and firearms possession (simultaneously), and for smoking marijuana (inside a police station). These incidents share a common root: They were orchestrated by members of the Free State Project—a plan, hatched in 2001, to get 20,000 libertarian activists to quit their jobs, sell their homes, and relocate to New Hampshire en masse. It is a political movement in the most literal sense.

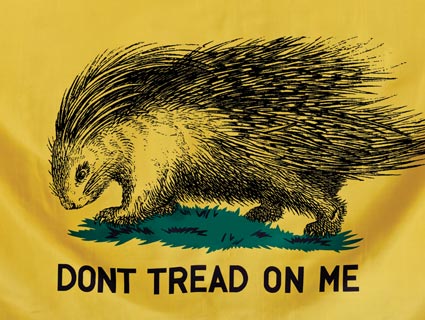

More than 11,000 people have pledged to move to the Granite State, and some 700 pioneers have already relocated and set to work pursuing their idea of a libertarian paradise. Along with civil-disobedience campaigns, Porcupines (as Free Staters have dubbed themselves, because they’re peaceful unless attacked) have promoted schemes to return the state to a precious-metals-based currency (Shire Silver, Liberty Dollars) and set up a hot line for reporting police abuses. Slowly, they have begun to infiltrate the ranks of state and local government; last November, 13 Free Staters won election to the New Hampshire Legislature. As the state gears up for its presidential primary early next year, it is in the midst of a political takeover.

New Hampshire has always held a special place among libertarians, who revere its lax gun laws, its lack of sales tax, and the freedom to crash a motorcycle without a helmet. And there’s the catchy state motto: Live Free or Die. But the Free State Project departs from that liberty-loving tradition in one key way: Its members aren’t migrating to Manchester and Concord and Keene to live under existing laws; they’re coming to remake the state in their image.

The idea has its genesis in a 2001 manifesto in the online journal Libertarian Enterprise by Jason Sorens, a University at Buffalo-SUNY political science professor who at the time was hammering out his dissertation at Yale. “What I propose is a Free State Project, in which freedom-minded people of all stripes…establish residence in a small state and take over the state government,” he wrote. If the newcomers played their cards right, Sorens reasoned, they could turn the state into a real-life Libertopia, the kind of autonomous enclave libertarians have been trying to piece together—usually on the high seas, always disastrously—for well over a century. (One such colony, founded in the South Pacific by a Nevada coin dealer, was conquered by Tonga in 1972; an earlier effort on the Haitian coast was destroyed by a hurricane.) They would succeed not by running away from society, but by engaging it head-on.

Later that year, Sorens helped form the Free State Project and held a referendum to determine the location; New Hampshire edged out Wyoming. Proximity to the Boston job market helped, but there was another, less obvious reason: The state’s government is uniquely susceptible (PDF) to the influence of a small but dedicated minority. The largest democratic legislative body in the English-speaking world is the British Parliament; the second largest is Congress; the third biggest, with 400 delegates for 1.3 million people, is the New Hampshire House of Representatives. With a $200-per-term stipend, it’s a terrible way to put food on your table, but no other state makes it easier for a determined activist to gain access to the mechanisms of power.

Free State legislators are currently pushing to decriminalize marijuana, permit the video recording of law enforcement officers, legalize the use of deadly force in self-defense, nullify health care reform, slash taxes, deregulate barbershops, and ban vaccinations in public schools. This isn’t the corporate-driven cutback crusade of Gov. Scott Walker’s Wisconsin; it’s closer to a Ron Paul revolution.

Dan and Carol McGuire relocated to New Hampshire from Washington state in 2005. “We decided if the Free State Project failed and we hadn’t moved, we couldn’t live with ourselves,” Carol says. Political novices, they both won seats in the House of Representatives (Carol in 2008, Dan in 2010).

They’ve taken different approaches to fighting tyranny. Carol’s goal for the 2011 session was culling anachronistic laws that have remained on the books through bureaucratic neglect. She succeeded in axing an 1895 statute, the result of lobbying by Big Butter, that requires margarine to be served in triangular containers so that diners don’t confuse it with the real thing. Dan had his sights on something of potentially much greater consequence. He and a few allies succeeded in passing a bill to eliminate the New Hampshire Rail Transit Authority, which is planning a high-speed line to Massachusetts. Their argument was simple: Government shouldn’t be in the business of building railroads. The state’s Democratic governor, John Lynch, vetoed the bill.

The McGuires represent the assimilationists, Free Staters who have embraced the state’s existing political framework and used their strength in numbers to exert influence. Then there’s Freeman, whose peculiar hybrid of Gandhi and Project Mayhem has drawn national attention to his faction’s antics. He is a host of the “Free Talk Live” radio show and a board member of the Civil Disobedience Evolution Fund, an organization dedicated to “helping good people who disobey bad laws.” When fellow Keeniacs have been arrested (which is often), Freeman and his friends have held barbecues outside the police station to show their support. That kind of attention-grabbing doesn’t sit well with some of his fellow Free Staters. Porcupines, after all, are supposed to bristle up only when provoked.

“I think some of the civil disobedience has been constructive and useful—and much of it has not been,” Sorens says. Jenn Coffey, a freshman Republican state representative who moved from Massachusetts in 2005, was equally blunt: “They want the project to be more than it is.”

Some activists, like Freeman, would like to see the police and fire departments converted into purely voluntary organizations. If residents want to pay for public services they could, but it should be optional. And if they don’t consent to anti-couch ordinances, well, they shouldn’t have to abide by them. Others, like the McGuires, believe the problem is too much government, not the existence of government itself. And therein lies the problem with attempting to create a libertarian utopia: No one—least of all libertarians—can agree on what it looks like.