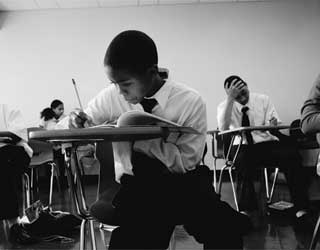

Photo by Kwaku Alston

Say “footprint” in a roomful of foodies and heads will nod: Obsessing Thinking about where your food comes from has been the most resilient trend this side of cupcakes. But what about where you eat? That’s where Marcus Samuelsson comes in: When he opened his high-end Harlem Restaurant, Red Rooster, he says, he aimed to “expand the dining footprint of New York.” Could he get high-end diners to travel north of 96th Street? Could he get the neighborhood to support an establishment where a plate of fried chicken runs $28? Two years in, the answer is yes: Red Rooster (the name honors an old speakeasy) is raking in the critical honors, and it’s expanding its own footprint by supporting a neighborhood farmers’ market and a culinary-arts training program for local youth.

Food, to Samuelsson, is about families, neighborhoods, and traditions—and about recombining them all in surprising ways. The chef is himself a cultural mash-up: Ethiopian by birth, Swede by upbringing, New Yorker by choice, with culinary training that involved “getting yelled at in English, German, French, and Spanish.” His new autobiography, Yes, Chef, recounts his remarkable journey (starting with his birth mother walking 72 miles, with her young kids, to get them treatment for tuberculosis). We sat down with Samuelsson in San Francisco after he joined MoJo staff and friends for what he described as “the best breakfast of my life.”

Mother Jones: At Red Rooster, you created the position of “greeter,” someone who is specifically not a bouncer, but who stands outside and says hello when you come in, and on your way out might point you to the subway or to a place to have a cocktail. This was in part to make your customers linger in the neighborhood?

MS: We want them to walk around in the community. We made a map, an artistic map, so people can know where else to go from here. If you had corn bread and beer with me and you decided to go to a jazz concert 20 blocks up, I’m fine with that because I brought you up here and now you are in the community. If you’re in the community and are having normal relationships within the community, the way you would behave on 23rd Street, the way you would behave in the West Village—that’s what matters. That’s where the greeter was important, not like a big bulky guy, but just a guy that’ll say “Hey, welcome back.”

MJ: People think of Harlem as being exclusively an African-American community, but it is such a diverse place—

MS: West African on 8th Avenue. Caribbean when you go across Grant. The larger body of the classic African American community. The Mexican community over here, the Puerto Rican community over there, the Italian strip right there. It’s very mixed, very melodic.

MJ: How does that enter your work?

MS: To me, those immigrant experiences are about eating with a spiritual context, and understanding what that means for each family, for each community. How it shows you how much protein, how much meat, what type of meat, what type of fish you should eat. Looking forward to a celebration on Saturday, giving away a goat or a lamb, when to fast, when not to fast. So at Red Rooster, I always keep an avenue open for the immigrant community. Swedish meatballs, Ethiopian spices. I would say that’s 30 percent of the menu. And 70 percent of the menu is a mirror of the Harlem community, and then we’re adding in the farmer’s market, seasonality. So we have fried chicken, but in the summertime it should be with pickled watermelon or green tomatoes, and in the wintertime it can be with a root vegetable puree. We have dirty rice and shrimp, manifested from the Caribbean community, but it might be with mizuna or nettle in the spring, and fried kale some other time. And then Mexican, Puerto Rican—we have a big roasted pernil, but we also have wonderful fish taquitos. It’s all about this community that is not monolithic, and I can understand that by walking, by looking at signs, by biking, by strolling up and down the avenue.

MJ: As a fellow immigrant, I’m curious about the specifics of your journey—it’s not like you can just decide to get on a plane one day and be a chef in New York City. Can you talk about what it took—

MS: All of my determination. My decision was made when I saw that there was a black Other—there was David Dinkins, mayor of New York. There was a black middle class, upper middle class. I didn’t see that in Europe anywhere. In Europe I couldn’t be anything but a black cook working for somebody. Which was fine, but my inspiration was to own, to be the chef. So I needed a place where there was an Indian doctor, a Jewish lawyer, a Korean teacher. In that environment, I knew I’d do well.

MJ: And Europe really didn’t, and doesn’t, have that.

MS: I love Europe, but we are still struggling with that kind of development. First of all, we don’t have a smart conversation about the difference between an immigrant and a refugee. A refugee can’t go back. An immigrant is someone—I chose to move to America. And I also have the option of saying hey, didn’t work out, I can move back. That’s a completely different story than someone who is locked in.

MJ: We tend to focus on the downsides of the immigrant experience. Are there ways that being an immigrant has helped you?

MJ: We tend to focus on the downsides of the immigrant experience. Are there ways that being an immigrant has helped you?

MS: America has been very open to immigrants in terms of laws, getting loans—it has been helping immigrants more than it’s been helping African Americans in starting a small business. That’s key, whether you’re starting a restaurant or a laundromat.

MJ: African Americans are few and far between at the top of the restaurant industry. What’s going to change that?

MS: First of all, there’s the fact that African Americans were the serving class for so long. It took hundreds of years for us to get out of the kitchen, so now it’s going to take probably 20 years for us to get back in. You need something to aspire to—and I accept that role, and others do—and then it takes a while to build. TV is a very important platform, because it means going from anonymous labor to visible labor.

MJ: You cooked the Obamas’ first state dinner. There’s got to be an affinity there—being the guy that people see on TV and say “That happens.”

MS: Yes. But remember, I got the dinner because I did my homework. I studied the First Lady’s [gardening] program, I looked into the fact that [the Indian prime minister] was a vegetarian. It goes back to what my training was, doing the homework, presenting a narrative, and executing.

MJ: Do you see other people fusing American tradition and multiple immigrant cuisines the way you do?

MS: I think we will see more of it as we are becoming more of a mixed nation. There is a wonderful restaurant in New York, Sushi Asuda. An American family decided to do one of the best sushi restaurants in New York City. They’re not Japanese, but they love the craft. Look what Rick Bayless did—a fascinating journey, true commitment to Mexico, and he’s not Mexican. But he understands the culture.

MJ: I first heard of your work in the ’90s when you were at Akvavit doing Scandinavian cuisine, and I remember being struck by how much of it was about salting and pickling and curing. People are so focused now on using things in season—it’s interesting that you’re drawn to techniques that let us use foods out of season.

MS: Pickling and curing is moving from being a necessity to a flavor enhancer. If I preserve a fish like raw lox—the way my grandmother did that, it took 48 hours. I do it for 12 hours, because I have a fresher fish, and I want that texture because we learned that from sushi and sashimi. She sliced her fish thin, and it tasted salty and she put a sweet mustard on it. I cut down on the sweetness and the saltiness because I don’t cure the fish that long—my goal is not to cure it so I can have it for six weeks. But still I want to cure it, because it ups the flavor. You have to know a lot about food to do that. You can read a recipe, but you’re not going to understand it.

MJ: Did you experiment like that when you were young? Or did that just start when you became a chef?

MS: After I became a chef. In the beginning, it’s all about knowing how to do it—only then are you allowed to do an offshoot. It’s a lot of Swedish pickling before you start adding rice wine vinegar and sesame oil. It was a long journey for me.

MJ: In the book, you talk about the boot camp culinary education that you had in Switzerland.

MS: I think the Germanic world works very well for that—there’s nothing wrong with being told what to do for a while. For me at least. Out of that I built my discipline, and out of that I built my own authorship of my own food. And a lot of chefs today, they just want to get to that part. You can do that, you can get lucky and it can be good, but you can’t create cuisine that way. We talk a lot about the [Baby Boom] generation, and we talk about the ’80s and ’90s kids. My generation is the generation in between. We’re old enough and young enough—we saw a lot of stuff. I saw the Berlin Wall fall. We saw Europe change through Russia, we saw 9/11. And also, as children of a generation that came out of World War II, you are humbled by your grandparents in many ways. But then you’re also told that everything just goes up, up, up, up. You have color TV, Europe became one, you can travel everywhere, at least until 9/11. And then everything changes again. I am a reflection of that.

MJ: The GenX chef.

MS: Yeah.

MJ: Speaking of generations—it struck me reading your book, and what you write about your ancestors in both Ethiopia and Sweden, that even in the affluent world we’re only a couple of generations removed from people who were dying of starvation. Our relationship with hunger has really changed.

MS: It’s a change in hunger, but also in labor. Before, a lot of hunger was very often matched by a lot of labor, so you got one big meal. Breakfast was really big, because you worked it off. Now you’re not so worried about where your meal is coming from, and you’re also not working it off. And even so we still have 10 million kids, in the richest nation in the world, who go to bed hungry. That’s not a small number.

MJ: Did you always think about food in these terms—in a broader context than what’s on your plate?

MS: At 24, I couldn’t think like this. It was all about, ‘look at how I can cook, look what I can do,’ and that was a very good space for me then. Going to Africa and living in Harlem had a big impact on me. You go to Africa and you see how much joy they have around food, but also how hard they fight to get fresh water. In Africa, you have no clean water, but you have good food options. In Harlem, everyone can shower and get fresh water, but you often have bad food options. So me being connected to both, I find that fascinating and inspiring. And if I have a big platform, which I have, I find it my obligation to do something about it. We have the platform, we have the mic, now let’s fill it with good.