Illustration by Jason HolleyIt’s late June in North Dakota, and Galen Grote and I are bouncing over his cattle ranch in a Chevy pickup with the radio tuned to “Hair Nation.” Grote’s vast fields of wheatgrass bring to mind Axl Rose getting a blow-dry—a wind-tossed mane of turf stretching across the fertile remnants of ancient glaciers and river deltas. The earthbound wealth here in the Missouri Plateau convinced Grote’s great-grandfather to homestead this land a century ago—long before anyone knew of the liquid riches beneath it.

Illustration by Jason HolleyIt’s late June in North Dakota, and Galen Grote and I are bouncing over his cattle ranch in a Chevy pickup with the radio tuned to “Hair Nation.” Grote’s vast fields of wheatgrass bring to mind Axl Rose getting a blow-dry—a wind-tossed mane of turf stretching across the fertile remnants of ancient glaciers and river deltas. The earthbound wealth here in the Missouri Plateau convinced Grote’s great-grandfather to homestead this land a century ago—long before anyone knew of the liquid riches beneath it.

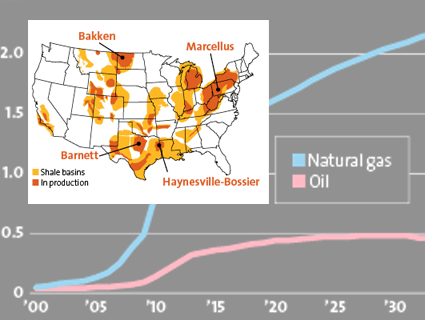

After passing sloughs full of coots and mallards, we arrive at the dusty pad where an Oklahoma-based oil company called Continental Resources has hit pay dirt. A gleaming new jack pump siphons up crude and flares off fireballs of gas. All over this part of the state, Continental’s rigs have corkscrewed through nearly two miles of limestone, gravel, and sandstone to tap the Bakken and Three Forks reservoirs, oil-rich bands of shale that formed millions of years ago from what was once an inland sea. This Sri Lanka-sized mineral vein straddling Montana, North Dakota, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan is now the heart of America’s new oil boom, the largest domestic find since Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay more than 40 years ago. Continental’s founder and CEO, Harold Hamm, the dominant player in the Bakken rush, estimates that there is as much oil here as has been discovered in the rest of the United States put together.

Tapping the Bakken has already made Hamm one of America’s richest oil barons, and North Dakota now rivals Texas as the top-producing oil state, with an economy hotter than a Houston sidewalk in August. In 2011, tax proceeds were up 44 percent from the year before, prompting a ballot measure that attempted (unsuccessfully) to abolish property taxes. Thousands of new oil jobs have given North Dakota the nation’s lowest unemployment rate (3 percent) and overwhelmed cattle country with an influx of fortune seekers. Ranching hamlets that once had five-minute rush hours now endure endless caravans of exhaust-spewing tanker trucks filled with oil, fracking fluids, and “hot loads” of drilling waste.

Some North Dakotans question whether their newfound prosperity is worth the price. Grote complains that Continental, which has leased rights to the minerals under his soil, is blanketing his fields with dust and oil waste. “They come in, you know, just balls to the wall and tear it up, do what they want, get their money out of it as quick as they can.” When a Continental pickup pulls up behind us at a pump jack, I walk over with Grote to hear the company’s side of the story, but the worker rolls down his window and tells us to leave. “Continental didn’t buy this land,” Grote reminds him. “From what I understand, this spot is Continental’s,” the worker insists. Grote stares back in icy silence, stroking his ZZ Top beard while displaying a bicep as thick as a cottonwood bough.

Battles between ranchers and oilmen might sound like relics of the Wild West—the stuff of films such as There Will Be Blood—but in North Dakota, they’re all too current. Continental beat other oil companies to the punch by signing more leases and pumping oil faster and more aggressively than anyone. But in its rush to cash in, the company has sometimes thwarted environmental laws, endangered workers, and overwhelmed small towns with more people and problems than they can handle.

Hamm—who declined to be interviewed for this story—is a man on a mission, one of the most outspoken evangelizers of a push to extract as much domestic oil as quickly as possible. “We could be completely energy independent by the end of the decade,” he told the Wall Street Journal last year. “We can be the Saudi Arabia of oil and natural gas in the 21st century.”

When Hamm talks, politicians listen. He is, according to the Forbes list, the 35th-richest American, worth an estimated $10 billion—more than William Koch, T. Boone Pickens, and David Rockefeller Sr. combined—and he isn’t shy about deploying that fortune. Prior to 2007, he had doled out just $46,000 to influence elections; since then, he has showered Washington politicos with $1.3 million and founded the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance (slogan: “Good things flow from American oil”). Over the past two years, he has given at least $1 million to right-wing causes supported by Charles and David Koch, the billionaire industrialists who helped bankroll the tea party.

In March, Mitt Romney named Hamm his top energy adviser. Though a largely ceremonial post, the choice signaled that Romney, who had advocated for clean power as governor of Massachusetts, was casting his lot with the oil and gas industry. Barely a month later, Hamm contributed $985,000 to Romney’s super-PAC. Shortly after that, Romney, in a speech in Virginia, extolled Hamm’s tale of hitting “that black gold” as the triumph of the little guy over big government. “This is how the founders envisioned America,” he stressed. “They didn’t want to have a country that was guided by a government; instead they wanted to have a country that was driven by free people pursuing their dreams.”

THE YOUNGEST of an Oklahoma sharecropper’s 13 children, Harold Hamm grew up in a one-bedroom house without electricity or running water. He’d often skip school to pick cotton. With money saved from working at a filling station and hauling oil-drilling mud, he bored his first well in 1971 and hit big on his second. Soon, while still in his 20s, he had a full-service oil exploration company.

By the late 1980s, though, Hamm’s luck began to sputter; a string of dry holes cost Continental more than $10 million. Other oil drillers were turning to natural gas, which was becoming easier to extract thanks to new technologies such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (a.k.a. “fracking). While fracking is more commonly associated with gas drilling, Hamm was among a handful of wildcatters who thought it could be used to squeeze crude oil from dense shale deposits in hard-to-tap locations. In 2004, Continental put this approach to the test in North Dakota, registering its rig under the name Jolette Oil to keep competitors off the scent. The experiment paid off, and Continental, as Hamm later put it, was “off to the races.”

Click here for more fracking charts.

Click here for more fracking charts.

By the time others recognized the Bakken’s potential, Hamm had already inked cheap mineral-rights deals up and down the state, paying some $200 an acre for leases that sell for up to 50 times as much today. This gave Continental an advantage, but it also put extreme pressure on Hamm to perform, since the typical lease expires in three to five years if drilling hasn’t commenced. “A lot of the mad rush in the first few years is companies that had leases trying to get wells drilled,” says Derrick Braaten, a Bismarck oil and gas attorney. Yet drilling in the geologically tricky Bakken runs $8 to $11 million per well, four to five times the cost of a conventional well in Texas. “The companies are trying to get their return on that as fast as possible so they can use that money to invest in a new well,” Braaten explains.

In Bismarck, North Dakota’s capital, the oil industry’s need for speed has created fundraising opportunities for politicians. The administration of Gov. Jack Dalrymple—who has received $20,000 from Hamm—has been granting drilling rights at a brisk pace: The number of permits has tripled in three years despite pleas from locals to slow things down. Nor did Dalrymple tap the brakes last year, when oil-patch towns complained that severe housing shortages prevented them from hiring new police officers. Instead, he pledged to install trailer homes in nearby state parks and fill them with state troopers. “We are doing our very best to keep up,” the governor told a crowd of oil executives last year. “I can promise that we will be faithful and long-term partners in your efforts to develop the Bakken Shale. And most of all, I can promise that you will have direct access to our state government at the highest level.”

Much of Dalrymple’s support involves looking the other way. Despite more than 3,300 oil field spills* in North Dakota since 2009, his Industrial Commission, which oversees drilling-related activities, has issued only 45 enforcement actions. Nor has the governor done much to discourage Continental and his other petroleum donors from squandering the natural gas that bubbles up with their oil—enough to power nearly 550,000 homes. Drillers recover most of that gas in oil states like Alaska, California, and Texas, but to do so here would require building pipelines and plants, forcing Continental to slow down. “The field covers 15,000 square miles, so it takes time to go and test what’s there and then build a gathering system and plant,” Hamm told the New York Times. As a result, more gas is burned off in the Bakken than in any other domestic oil field, releasing as much carbon dioxide as nearly 400,000 cars or a new coal power plant.

In its rush, Continental has ridden roughshod over environmental laws. Documents acquired by ProPublica show that it has spilled at least 200,000 gallons of oil in North Dakota since 2009, far more than any other company. That year, in one of its few formal citations against oil companies, the state’s health department fined Continental $428,500 for poisoning two creeks with thousands of gallons of brine and crude, but later reduced the amount to $35,000. Around the same time, during a thaw, four Continental waste pits overflowed, spilling a toxic soup onto the surrounding land. The Industrial Commission said it would fine the company $125,000, but it ultimately reduced the sum to less than $14,000, since “the wet conditions created circumstances that were unforeseen by Continental.”

The company’s rapid expansion also has coincided with a spike in accidents. In July 2011, a Continental rig exploded near the town of Beach, badly injuring three men—two had burns covering more than half their bodies. Hamm told a reporter that it was the first rig explosion in company history—although one rig worker had been crushed to death back in 2007—but two months later a second rig blew up, forcing the evacuation of 25 homes. Last year, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration cited Continental for a dozen workplace safety violations.

IN THE PRAIRIE outpost of Tioga, between the Wildcatz Grill and the brand new Black Gold Suites, the two-pump—soon to be six-pump—Kum & Go gas station is stacked floor to ceiling with cases of Red Bull. The “Now Hiring” sign on the door is practically a blur, what with the parade of men passing through to buy tins of Skoal and gas up their mud trucks. The cashier tells me about the wasted guys who crumpled their car into the storefront the other night: “They meant to push the brake and they pushed the gas.”

The deluge of new arrivals has nearly tripled the price of an average two-bedroom house from $65,000 five years ago to north of $175,000 today, and has given rise to vast “man camps” that look like FEMA scenes—dozens of trailers crammed into treeless parking lots. Locals aren’t faring much better. On the day I visited, the front page of the Tioga Tribune announced that the paper had lost its lease and would relocate to a nearby town because it couldn’t find affordable office space. “The unabated influx of people has basically outgrown our city infrastructure, our health care infrastructure, and our community values system,” says Gary Ramage, the only full-time physician in McKenzie County. Since 2006, the number of ambulance calls in the county has increased 14 times faster than its population, and Ramage estimates that three injured oil workers show up daily at the once-quiet emergency room.

Correction: The original version of this article, which ran in our November/December 2012 issue under the headline “Drill, Baby, Drill,” misidentified the type of spills recorded in North Dakota since 2009.

Continental would rather not discuss its role in these growing pains. The company’s workers in North Dakota are not allowed to speak with the press, a secretary in the company’s Tioga field branch explains as she hands over a card with phone numbers for an Oklahoma PR office. When I turn it over, I realize the card was meant not for reporters, but Continental employees. It counsels against providing the press with “unnecessary elaboration,” details on “extent of injuries/fatalities” from accidents, or “statements reflecting fault or blame.”

For an uncensored view of the Bakken, I head over to Whispers, a strip club and blackjack house in Williston, an hour to the west. According to the Census Bureau, Williston is the nation’s fastest growing “micro area”—its 2011 population was up 16 percent from the 2010 census. One of the owners of Whispers, a rotund man in a Harley shirt, says business was so slow five years ago that he and the bartender would spend most of the night playing cribbage. “Now I look around at the customers, and I don’t recognize anybody.” He claims Williston’s male-to-female ratio is around 120-to-1 nowadays. In any case, the strip club is booming: “They said they will be drilling here for the next 30 years,” he says as a dancer across the bar pretends to suffocate a guy with her breasts. “They said when it’s all said and done, there will be an oil well here every 1,000 feet. It will look like Odessa, Texas.”

Troy, a baby-faced 20-year-old from Oklahoma who’s nursing a Bud Light longneck, is the same age as Hamm was when he started the company that became Continental. He hasn’t heard of his fellow Oklahoman. Then again, pulling down six figures as a rig worker doesn’t leave him much time to scrutinize the Forbes 400 list. “I’m the little guy making good money right now, but I’m still the little guy,” Troy says. “I’m working my ass off.”

OVER AT THE North Dakota Heritage Center, a popular field trip destination on the leafy grounds of the state Capitol, the fossilized mastodon and stuffed buffaloes have a new neighbor: a shiny 55-gallon drum labeled “Crude Oil.” It’s part of a permanent oil industry exhibit under construction thanks, in part, to Hamm’s recent $1.8 million donation.

The exhibit will inhabit a new Continental Resources-sponsored “Inspiration Gallery.” “The more we look at it, the more it kind of relates back to the homestead era,” says Claudia Berg, who is coordinating the expansion, as she shows off a fancy scale model. “There’s families living in small little trailers and whatnot; they’re the same size as what a homestead shack was.”

Hamm and his company also have doled out school backpacks with Continental logos, donated $50,000 to the Tioga fire department, and regraded miles of public roads needed to service Continental’s wells. A renovated emergency room in the town of Crosby will bear Continental’s name. But Hamm’s largesse has also raised eyebrows in this fiercely independent state. “He wouldn’t be giving that contribution unless he wanted something for it,” says Don Morrison, executive director of the Dakota Resource Council, an environmental group representing farmers and ranchers.

Hamm’s top political priority here is to reduce North Dakota’s 11.5 percent oil tax—fairly high by national standards—which accounted for most of the $50 million Continental reportedly paid in state taxes last year. He has joined forces with Ed Schafer, the state’s former GOP governor, who in January 2011—just as the Legislature was debating how to dole out the budget surplus—founded a one-cause advocacy group called Fix the Tax. “If you’ve had enough about high taxes allowing more spending each year, then join us,” Schafer beckons in a YouTube clip. Late last year, he joined Continental’s board of directors with a compensation package worth more than $770,000.

IN JULY 2011, Hamm flew to Washington to join Bill Gates and Warren Buffett at a philanthropy conclave organized by the White House. Hamm later told the Wall Street Journal that he had pitched the president on the merits of more drilling, arguing that America has enough oil in the ground to replace what it buys from OPEC. According to Hamm, Obama was unimpressed, stressing instead that the nation’s future lies with alternative energy and predicting that battery-powered cars would soon get the equivalent of 130 miles per gallon. “Even if you believed that,” he told the Journal, “why would you want to stop oil and gas development? It was pretty disappointing.”

Click here for more fracking charts.Obama is hardly a foe of oil and gas. While opposed to industry tax breaks, he pledged to open more of the Arctic to offshore drilling, gave a nod to fracking in his convention speech, and fast-tracked federal permitting for drilling in the Bakken. Hamm has made a good chunk of his fortune during the Obama presidency. Still, he is justifiably concerned about what comes next. Continental, which has vastly outperformed its rivals in the five years since it went public, has shed more than a fifth of its stock value since February—costing Hamm and his family some $2.5 billion.

Click here for more fracking charts.Obama is hardly a foe of oil and gas. While opposed to industry tax breaks, he pledged to open more of the Arctic to offshore drilling, gave a nod to fracking in his convention speech, and fast-tracked federal permitting for drilling in the Bakken. Hamm has made a good chunk of his fortune during the Obama presidency. Still, he is justifiably concerned about what comes next. Continental, which has vastly outperformed its rivals in the five years since it went public, has shed more than a fifth of its stock value since February—costing Hamm and his family some $2.5 billion.

The company is now in a bit of a pickle. It can no longer hope to ink sweetheart mineral leases like the ones Hamm snatched up early on, and it faces far higher operating costs than its rivals with conventional drilling operations. Lacking sufficient pipelines, Continental exports much of its Bakken crude by truck and train, which adds as much as 30 percent to its costs. Fixing that, Hamm seems to have concluded, merits a bit of arm-twisting. He has hired political operatives including Mike Cantrell, a veteran of oil industry trade groups, and Blu Hulsey, a former spokesman for one of Big Oil’s favorite senators, Oklahoma Republican James Inhofe. And he came out swinging in the media last winter, after the Obama administration announced that it would delay approval of the environmentally controversial Keystone XL pipeline linking Canada’s tar sands to Texas’ oil refineries. (The pipeline would also carry oil from the Bakken, allowing Hamm to cut his costs substantially.) Asked on CNBC’s Squawk Box to comment on the “dirty” reputation of tar sands oil, Hamm brushed off the concerns, insisting that North Dakota needed the pipeline to export “the best-quality oil anywhere.”

Hamm is also leading the fight against Obama’s proposal to close oil industry tax loopholes. His Domestic Energy Producers Alliance has spent more than $500,000 on lobbying, with the tax issue as its top priority. In written testimony for a June Senate hearing, Hamm claimed that eliminating the subsidies would force his company to cut back production by one-third. “The unintended consequences if we are not careful, by changing these rules, could be devastating,” Hamm said. “We could stop this energy renaissance.”

Like other fracking tycoons, such as super-PAC high roller Trevor Rees-Jones (read my profile of him here), Hamm has thrown his full weight behind Mitt Romney, speaking out on his behalf and hosting a $1,000-a-plate fundraiser for him in Oklahoma City. (As of September, the fossil fuel industry had given Romney and his super-PAC some $14 million.) In return, the candidate became a full-throated cheerleader for oil and gas interests. “My view is that we don’t know what’s causing climate change on this planet,” Romney said during the primaries. “And the idea of spending trillions and trillions of dollars to try to reduce CO2 emissions is not the right course for us.”

One thing is certain: Whoever is in the Oval Office next year can bank on the Bakken boom. A rig every 1,000 feet and a millionaire every mile might not be that far away. “A lot of people who’ve had a hard time in our community are now doing very well for themselves,” says Nikki Darrington, the wife of a farmer and water-well driller whom I meet at a street festival in Watford City. She cradles her 11-month-old, Gavyn, who has just wowed the festival’s baby pageant with his seersucker onesie. “I don’t mind the man camps,” Darrington adds, but “our roads are crap and our grass is gone. I used to get a wave from every single person, and now I know that they are not going to wave because they are too busy focusing on the street because they know they are going to get run into by a semi. And the bar fights! We’ve never had stabbings and shootings. With all the good, there comes a lot of bad too.”

Just ask the newcomers. “This place is a shithole, and it’s a really expensive shithole,” says Pepper, a veteran roustabout from Oklahoma who is loading up her car on the crowded gravel lot where she and her husband pay $900 a month just to park their Prowler. They were hoping to save up enough money to open a bar and grill, but not in North Dakota. “Who really wants to move up here?” she adds as her husband drags on a Marlboro Light, his thick denims caked in red dust from a long day servicing oil tanks. “When all these guys are gone—maybe not this year or next year, but 5 years down the road, 10 years if they are lucky—what’s going to happen? The economy is going to go right back down where it was.”