Conservation International

One group that’s been keeping a close eye on climate change is wine growers. Since a 2006 study predicted global warming could fry over 80 percent of the US’s wine grapes, vinters have been planning new heat-resistant varietals, adopting big-data-driven water saving techniques, and mapping out what could become the new Napa Valleys of a warming world.

That last trend is the focus of a new study out today that examines how shifting wine cultivation geography could have implications for endangered species. Lee Hannah, an ecologist at Conservational International, used a suite of global climate models to plot where ideal wine conditions will migrate to as temperatures warm and precipitation patterns fluctuate.

“In a lot of these places, what’s there now is good wildlife habitat,” Hannah said.

Up to 73 percent of the area currently suitable for wine cultivation could be lost by 2050, according to the study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. While temperate places like inland California and Mediterranean Europe lose good wine country, other, cooler or higher elevation areas, like the Northwest US and mountainous parts of China, are likely to open up for cultivation.

Unfortunately, Hannah and his colleagues found, some of those areas are already home to animals like grizzly bears and pandas, respectively, that already have enough conservation issues on hand without having to negotiate a sprawling new vineyard in the middle of their migration path. The problem goes the other direction, too: Stick a winery in the middle of a moose’s stomping grounds, Hannah said, and he’d “love to go in and eat wine grapes.”

By 2015, global wine consumption is expected to rise by nearly two billion bottles, an increase of 4.5 percent since 2006, with China’s growing middle class boosting the country into the top five world wine markets. And while China now imports most of its wine from France, Australia, and the US, Hannah predicts the Chinese could be sipping more home-grown wine within a few decades.

But, he said, “turns out the best place to produce wine in China is exactly the mountains that harbor pandas.”

Hannah’s study also examined the impact of decreasing rainfall on an industry that, in many places, already exacerbates water shortages. In California, for example, total wine-suitable area could decrease by as much as 70 percent in the next four decades—but declining precipitation could still leave more than 30 percent of that smaller area under water stress.

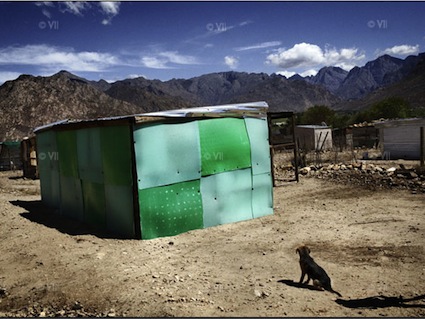

Conflict between wine and wildlife is already being addressed by groups like the World Wildlife Fund’s Biodiversity and Wine Initiative, which pairs conservationists with wine growers in South Africa’s ecologically rich Cape Floral Region. But Hannah said the wine industry globally will need to pay more attention to the issue in the future, and work together to ensure the world’s appetite for reds and whites doesn’t drive any critters to extinction.

“This is not under the control of any one vineyard,” Hannah said. “This is the next natural step for the industry, and it takes collaboration to consider how they might protect wildlife.”