<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=camera+ban&search_group=#id=143476063&src=2BiZ1B2CjSMU1zGN8VvJeg-1-59">Microstock Man</a>/Shutterstock

Animal rights activists filed a civil lawsuit on Monday contesting the constitutionality of a Utah law that bans recording at an agricultural facility without the owner’s consent. The suit, which asks the court to strike down a law that Gov. Gary Herbert (R) signed in March 2012, is the first challenge to this type of “ag gag” law.

The plaintiffs in the suit include PETA, the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF), environmental journalist Will Potter, and animal rights activist Amy Meyer. Meyer was charged with violating Utah’s law in February after she filmed a tractor carrying away a downed cow outside a meatpacking facility. She was the first person to face prosecution under an ag gag law in the US. The charges against her were later dropped because she was standing on public property while filming, but Meyer wants to prevent future charges against her and other activists.

“Utah should be ashamed of itself for passing a law to keep animal abuse a secret,” Jeff Kerr, general counsel for PETA, told Mother Jones. “The Utah legislature should be passing laws to put cameras in slaughterhouses and factory farms to expose and end abuse, as opposed to keeping it secret to protect their profits.”

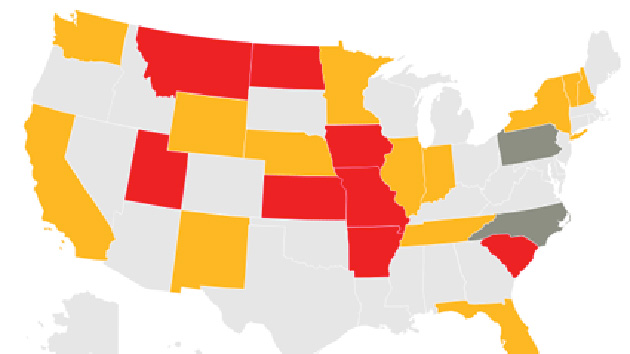

Utah was one of four states to pass laws criminalizing whistleblowing on agricultural facilities in 2012. In a recent feature for Mother Jones, Ted Genoways investigated the spread of so-called “ag gag” laws, which have been introduced in 12 more states in 2013. A total of eight states have now passed this type of legislation.

In Iowa, the law prohibits people from obtaining employment under false pretenses, like providing a false name or lying about employment history, in order to film animal abuse. But Utah’s law is even stricter, making it illegal to seek employment at an agricultural facility with the intention of creating a recording inside the facility, even if the prospective employee does not provide false information on the job application. Justin Marceau, a lawyer for ALDF, said the groups decided to challenge Utah’s law first because the charges brought against Meyer earlier this year show that “police and prosecutors are serious about enforcing it” in the state.

The complaint, which names Utah Attorney General John Swallow and Gov. Herbert as defendants, alleges that the law’s primary purpose is to “stifle political debate about modern animal agriculture by criminalizing the creation of videos or photos from within the industry made without the express consent of the industry.” The law also prevents the public and government officials from “learning about violations of laws and regulations designed to ensure a safe food supply and to minimize animal cruelty,” the complaint argues.

The plaintiffs say the law violates the Constitution. “The statute takes a content- or viewpoint-based discrimination, singling out certain types of speech or messages for less protection,” said Marceau, who is also a constitutional law professor at the University of Denver.

A spokesperson for the Utah Attorney General’s Office told Mother Jones that Swallow had not yet had a chance to review the complaint and could not comment on it. Herbert’s office also declined to comment.

The plaintiffs argue that Utah’s ag gag law could have consequences beyond preventing the exposure of animal abuse. “These laws have implications for union organizers and exposing other kinds of abuses that may go on behind closed doors,” said Kerr. “The law as drafted would prevent someone from filming bad employment practices or unsafe working conditions on factory farms and slaughterhouses.”

Plaintiff Will Potter, who first posted Meyer’s video online, said that the law could also affect journalists covering the issue. “Ag gag puts my sources at risk of prosecution for speaking with me or providing me their footage,” Potter told Mother Jones. “No journalist should have to choose between not reporting a story that is of national concern and putting a source in jail.”

Proponents of the law have argued that this is a private property issue and that activists should not be allowed to record on someone’s property without their consent. But the plaintiffs say the law is designed to prevent the exposure of abuse at agricultural facilities. “The reality is we celebrate undercover investigations in all sorts of contexts; if somebody gets into a kitchen of a restaurant and shows there’s gross things going on, we’re really happy to learn that,” said Marceau. “Here we have the agricultural industry saying, ‘We’re special, we shouldn’t be subjected to this investigative reporting treatment.'”