Buried in a Brazilian television report on Sunday was the disclosure that the NSA has impersonated Google and possibly other major internet sites in order to intercept, store, and read supposedly secure online communications. The spy agency accomplishes this using what’s known as a “man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack,” a fairly well-known exploit used by elite hackers. This revelation adds to the growing list of ways that the NSA is believed to snoop on ostensibly private online conversations.

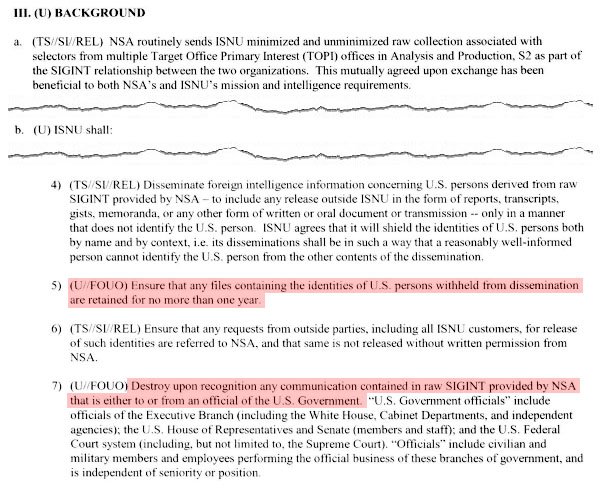

In what appears to be a slide taken from an NSA presentation that also contains some GCHQ slides, the agency describes “how the attack was done” on “target” Google users. According to the document, NSA employees log into an internet router—most likely one used by an internet service provider or a backbone network. (It’s not clear whether this was done with the permission or knowledge of the router’s owner.) Once logged in, the NSA redirects the “target traffic” to an “MITM,” a site that acts as a stealthy intermediary, harvesting communications before forwarding them to their intended destination.

The brilliance of an MITM attack is that it defeats encryption without actually needing to crack any code. If you visit an impostor version of your bank’s website, for example, the NSA could harvest your login and password, use that information to establish a secure connection with your real bank, and feed you the resulting account information—all without you knowing.

Browsers are supposed to automatically foil MITM attacks, John Hopkins University cryptography expert Matthew Green told me. They rely on data from of certificate authorities, which verify the legitimacy of websites and issue them certificates, or digital stamps of approval. Browsers automatically ask for these certificates and alert you if they don’t exist—you may have encountered such pop-up warnings.

But here’s where that system breaks down: Not all certificate authorities are completely trustworthy. “If you are big enough and spend enough money,” Green says, “you can actually get them to give you your own signing key”—the signature that they use to certify websites. With that, the NSA could create a fake certificate for any site on the internet, which is probably what it did when it impersonated Google, Green says. “This is actually relatively easy to do,” he adds, “because there are so many certificate authorities”—between 100 and 200.

Major MITM attacks are rare, as far as anyone knows, but they’ve happened before. In 2011, hackers breached the Dutch certificate authority DigiNotar and used stolen certificates to spy on internet users in Iran for weeks, an investigation later found. The Dutch government eventually seized DigiNotar—and Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla blocked all of its certificates.

MITM attacks also have downsides for attackers. For instance, Google Chrome maintains its own list of the public keys for Google webpages; the browser sends an alarm to Google headquarters if it detects any attempts to forge those sites. It has detected at least two MITM attacks this way, Green told me. “MITM is a really risky attack,” he says. “You have to know that nobody is looking at those services in order to make it work.”

The use of MITM attacks by the NSA was discovered by journalist Glenn Greenwald among the thousands of documents given to him by Edward Snowden in June. The story aired this past weekend on the Brazilian news station TV Globo, and was cowritten by local reporter Sonia Bridi. It detailed NSA’s use of MITM attacks against Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petrobras, but also mentioned that they’d been used to intercept information from Google servers.

Google has been redoubling its efforts to thwart NSA snooping, though its not clear whether those efforts include new ways to thwart MITM attacks. The company responded to detailed questions from Mother Jones with a short statement: “As for recent reports that the US government has found ways to circumvent our security systems, we have no evidence of any such thing ever occurring,” said spokesman Jay Nancarrow. “We provide our user data to governments only in accordance with the law.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified “Flying Pig,” a surveillance program run by the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), as being run by the NSA. The story also incorrectly described the way that certificate authorities authenticate websites.