Greg Williams/FOX

This article contains some major spoilers for previous seasons of 24.

In late 2004, Rabiah Ahmed was working at the Washington, DC-based Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) when its communications department received an email from the Hollywood Reporter. The reporter wanted the Muslim advocacy group to comment on the then upcoming fourth season of the popular, critically acclaimed Fox series 24, which was set to premiere in early January 2005. The season in question featured a Muslim-American Los Angeles family—that happens to lead an Islamist sleeper cell.

“It kind of caused a bit of concern to us as an advocacy group for American Muslims, because it was a sensitive time for Americans Muslims, as you can imagine,” Ahmed says. So CAIR reached out to Fox and 24‘s producers, who responded by inviting them to a meeting in LA. At that meeting, Ahmed and her colleagues (along with other representatives of Muslim-American communities) discussed their concerns with members of the 24 creative team. “They were very, very receptive,” Ahmed recalls.

In the months and years following that meeting, CAIR and the 24 team maintained an open dialogue (CAIR continued to voice concerns over season storylines). And in February 2005, 24 aired a special PSA, read by their star Kiefer Sutherland, who plays counter-terrorism agent Jack Bauer, emphasizing that “it is important to recognize that the American Muslim community stands firmly beside their fellow Americans in denouncing and resisting all forms of terrorism.” Fox consulted with CAIR in writing the disclaimer.

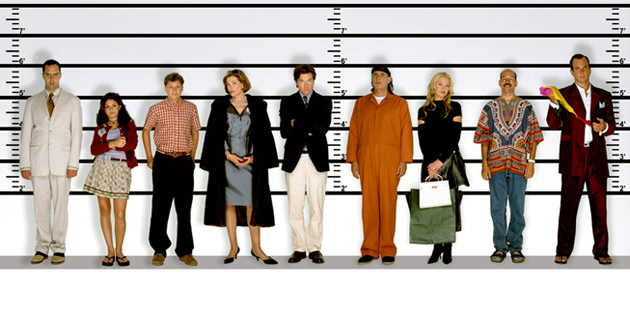

“They didn’t have to do what they did,” Ahmed says. “There have been other times we’ve dealt with the entertainment [community] and got no reaction. So we didn’t think it was just a PR move.” The producers of 24 may have placated CAIR. But the show, a real-time action-drama that originally aired on Fox from 2001 to 2010 (and returns on May 5 as 24: Live Another Day, a limited event series), didn’t just face criticism for its depiction of Muslim and Muslim-American killers. It was routinely criticized as torture-happy, right-wing entertainment.

The show’s depiction of torture got so bad that people working at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp reportedly got a lot of ideas for interrogation techniques from Jack Bauer. In November 2006, US Army Brigadier General Patrick Finnegan and several military and FBI interrogators flew to California to meet with the 24 crew to tell them that their show encouraged illegal conduct and negatively affected the training of American soldiers. “I’d like them to stop,” Finnegan said at the time. “They should do a show where torture backfires.”

The series also earned plenty of praise from conservatives for its simplistic (and dead wrong) perspective on Bush-era torture and civil liberties. Wall Street Journal economics writer Stephen Moore once said on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher that “[Jack Bauer] should run the CIA.” There’s a season of the show in which an analogue for Amnesty International and the ACLU is portrayed as an enabler of the enemy. Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld are among the show’s hardcore fans. And 24 co-creator Joel Surnow is a self-described “right-wing nut job.”

But here’s the dirty little secret about 24‘s initial eight-season run: It actually was a pretty damn liberal TV show.

“While it’s true that the show is primarily about consistent and ever-increasingly dangerous threats to the national security of the United States, it isn’t necessarily a vehicle for a conservative security agenda,” University of New Brunswick professor Jennifer Weed (who co-edited the book 24 and Philosophy: The World According to Jack) says. “In many cases, the series depicts the tragic implications (personal and political) of doing what is thought to be necessary to maintain an apparently fragile national security.”

24‘s portrayal of politicians skews to the left. Perhaps the most beloved character in the 24 universe is David Palmer (played by Dennis Haysbert), a tough, charismatic Democratic senator who becomes the first African-American president of the United States, and a close friend of Jack Bauer’s. (Haysbert has said that his character was shaped by his high opinion of Bill Clinton, Colin Powell, and Jimmy Carter, he even argued that Palmer helped lay the groundwork for public acceptance of a real-life black commander-in-chief.)

David Palmer. Via 24.Wikia.com

David Palmer. Via 24.Wikia.comIn season two, Palmer faces the biggest crisis of his presidency when a nuclear bomb nearly detonates in Los Angeles. Government agencies receive intel that implicates officials from three Muslim countries in the plot. Palmer asks Congress for a declaration of war, but backs down after Bauer suspects that a band of ruthless, amoral capitalists faked an international Muslim conspiracy. Bauer is proven right, and military engagement is averted at the last minute. During the season finale, President Palmer chastises his cabinet for their warmongering, saying that the country should enter a war only “after the strictest standard of proof has been met.”

This episode aired in May 2003, just two months after the US-led invasion of Iraq. The 24 team might not have known it at the time, but their second season—bogus intelligence, war, disastrous foreign-policy decisions—functions as a harsh critique of the Iraq War and the manipulation of intel that led to it.

Moreover, season two shows Palmer to be a vigorous force in combating violent anti-Muslim bigotry. Following the nuclear incident, mobs surround peaceful Muslim-American communities, demanding that the federal government intern them. In response, Palmer—in full-on, righteous anger mode—orders in the National Guard, and tells his staff, “We will not put up with racism or xenophobia. If this is where it’s going to start, this is where it’s going to stop!”

If 24‘s second season can be interpreted as an anti-war, anti-racism saga, then its fourth season can be viewed as a critique of American defense contractors and as a portrait of an incompetent and weak Republican president. Toward the middle of the season, it is revealed that McLennen-Forster (the third-largest US defense contractor in the 24 universe) ignored federal regulations, thus enabling a jihadist cell to use their technology. Bauer ends up winning a bloody battle with Blackwater-style McLennen-Forster commandos—but only with the help of two America-loving, gun-shop-owning Muslim brothers.

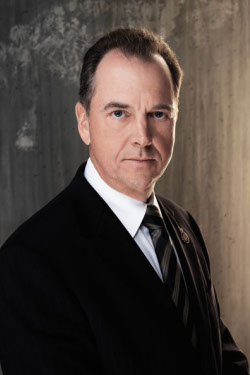

During this season, we also meet Republican Vice President Charles Logan (Gregory Itzin), who is sworn in as president after his predecessor is wounded in a missile attack on Air Force One. Logan’s first hours as president are defined by his inability to handle pressure, a failure of leadership that compels him to summon the liberal Palmer to advise him through the crisis and save the day. In the fifth season (which won five Emmy Awards, including Outstanding Drama Series), it’s revealed that the conservative, Nixonian Logan is behind the day’s new round of terrorist attacks. His motive? To stage-manage a false flag operation that would justify a US military deployment in Central Asia to ensure the steady flow of foreign oil for American consumers. (At this point, you won’t be blamed for thinking that 24‘s fifth season was co-written by Michael Moore.)

24‘s liberal streak would only continue in subsequent seasons. For instance, the sixth season illustrates the moral horror of interning large numbers of Muslim-Americans in response to a wave of bombings. The seventh season’s primary antagonists work for another shady private military contractor—one that arms mass-murdering African warlords. Season seven also features President Allison Taylor (Cherry Jones), the first female president of the United States; Jones has described her character as a cross between Eleanor Roosevelt, Golda Meir, and John Wayne, and has said that Taylor and Obama have similar politics. Season eight is big on promoting peace between the United States and the fictional Islamic Republic of Kamistan, a clear stand-in for Iran.

But more interesting is the fact that the series did, in spite of itself, undergo a soft evolution on the ethical and practical questions of “enhanced interrogation.” In season seven, Janeane Garofalo (well-known as a staunch liberal) plays Janis Gold, an FBI analyst who repeatedly argues against torture and civil liberties violations. There are characters who remind Bauer throughout the season that rules against torture are “what make us better.” And near the end of the season finale, Bauer confides in a friend how he wrestled with the moral dilemma of torture his whole career, and that he knows in his head—if not his heart—that laws banning torture are smart and just. (In real life, Sutherland has said that torture is terrible counter-terrorism policy and that Gitmo should be shut down.)

The first time audiences saw waterboarding used on 24 was near the end of its eighth season. The method is used on traitor and counter-terrorism analyst Dana Walsh (Katee Sackhoff), and it is portrayed as a horrific act that fails to extract any useful information:

Via 24.wikia.com

Via 24.wikia.comAnd during that same season, Bauer commits what might be the most gruesome torture ever shown on 24. In an act of revenge, Bauer subjects the agent who murdered his lover to a blowtorch and other instruments. It’s ugly, it’s prolonged, and makes Bauer seem more like a psycho than the hero we’ve long rooted for. After repeated cuts and burns, the agent still won’t talk. Bauer slams his hands down on a table and says to himself, “This isn’t working!“—a view of brutal interrogation that he had never bothered to express before.

These moments in the eighth season certainly don’t retract everything else that 24 asserted about the efficacy of torture. But it did act as something of a mild corrective—an acknowledgement of the legitimacy of the liberals’ side of the debate over Bush-era abuses.

It’s easy to write off the liberal politics of 24 as thematic window-dressing. Hollywood and TV action writers, whatever their politics, often infuse their product with a sort of gun-toting liberalism in order to make characters more sympathetic (liberalism = compassion, basically). But the thing with 24 is that the liberal window-dressing was pervasive—and if that’s the case, it doesn’t really matter what the producers’ personal politics or motivations were. What you see when you fire up an old season of 24 is, at the very least, as much a liberal narrative as it is a conservative fantasy.