We were on the edge of the desert near Barstow, perched on the side of a freight train that was picking up speed, when my doubts began to take hold.

Steven “Bo” Keeley and I had been introduced by chance. A year earlier, I had gone to Oakland to meet up with a friend, an East Bay radical of the Occupy sort who had lured me west with the promise of hopping freights. I had long been fascinated by the notion, picking up scraps of wisdom here and there—avoid the “bulls” (hobo slang for railroad security); watch out for tunnels; pack plenty of rope. The plan was to catch a northbound to Mount Shasta and thumb our way back. But something came up. In the meantime, my friend told me, she had a book that might tide me over. It was the memoir of a hobo she’d met once over dinner, a real Renaissance tramp, who takes groups of corporate executives with him on freight-hopping adventures. Nice enough guy, a little boisterous—and a prolific composer of emails.

Keeley.

The first thing you’ll discover about Bo Keeley is that his Wikipedia page reads like Indiana Jones. “Bo’s Wikipedia entry reads like Indiana Jones,” states the about-the-author page of one of his most recent books, which details his past as a veterinarian, a former national racquetball champion, and the most-requested substitute teacher ever to be fired during a playground war in Blythe, California. It’s not an entirely fair comparison—did Henry Jones Jr. ever claim to have guided “twenty Brazilian evangelists with a penlight from a jungle bus crash” or chased “rhinoceros horn smugglers after being deputized and armed with a pistol in Namibia”? Many of these claims are sourced to Keeley himself, making the page a matter of some controversy. But it’s that muddy trench between man and myth that makes it such an alluring document. As one Wikipedia editor put it, “Due to the uniqueness of the individual, some hyperbole is understandable.”

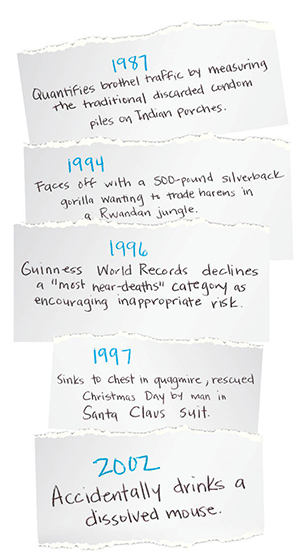

Among other exploits, Keeley claims to have applied for a Guinness world record for most near-death experiences (which he scores on a one-to-nine scale of “Catman points,” based on how many of a cat’s lives would have been snuffed out), brokered deals for the nation’s leading hedge fund manager, and been one of the only gringos to ride the freight trains from southern Mexico to the US border. Last year, tens of thousands of migrants rode the so-called “Train of Death” fleeing rape, murder, cartels, and crushing poverty—all of which accompanied them on La Bestia. Keeley did it because it sounded like a good time.

Keeley is a particularly social kind of loner, and he has attracted an intriguing band of followers who tag along on and subsidize his adventures. On his website, amid writings, photos, and a detailed timeline of his first 65 years on Earth, he advertises a travel service called “Bo Keely Tours,” inviting working professionals to break out of the monotony of their desk jobs and risk life and limb with him on the rails. (He spells his name without the third “e” when he’s writing because he wants to maintain a distinction between his traveler persona and his legal identity, or, depending on when you ask him, because it’s easier to sign autographs.) The Keeley package includes the option of staying at homeless shelters or bivouacking in encampments known as hobo jungles. The less adventurous sign up for spelunking trips in abandoned mine shafts or treks across the Mexican desert. In turn, Keeley’s “executive hoboes”—an almost exclusively white, almost exclusively male fraternity of lawyers, programmers, researchers, entrepreneurs, and investors—have welcomed him into their world and in many cases their homes. He’s been feted by financiers and invited to exclusive anarcho-capitalist Aspen retreats, floating in and out of his high-rolling friends’ lives like their very own Neal Cassady. What, I wondered, attracted them to Keeley and his lifestyle? Were his adventures simply Outward Bound for the Burning Man set? Perhaps Keeley, himself a devotee of Ayn Rand, offered a portal for something deeper. Perhaps he was a sort of objectivist folk hero who reminded them going Galt was possible, even if they never would. Or maybe they just really liked trains.

I decided to sign up. In an email, I told Keeley I wanted to catch out with him to see what he sees. And frankly, because I wasn’t sure he was real.

After nine hours in the Barstow railroad yard—nine hours hiding from the bulls while climbing over black tankers in 95-degree heat—the experience was all too real. We were crouched on the front grill of a container car going 5 mph toward Los Angeles, back to where we had come from, and Keeley was telling me to jump. I tossed my bag from the car, checked my footing, and leaped forward, tumbling, with the grace of a sinking barge, on my face. One track over, a mile-long train gave a jerk. Eastbound. Keeley, who’d managed to dismount at a graceful jog, hopped on, and beckoned for me to come. What else could I do? Two hands grabbed the ladder, then one foot, and now—steady—I was on. Our knees were inches away from the grinding wheels as the train picked up speed past a watchtower, past yard workers on four-wheelers, past one last spotlight, and at last into the open. A woman in a convertible jabbed at her driver to look up, honey, look at the hoboes! For the first time all day there was a breeze, and the mountains provided shade from the fading sun as we sped through the Mojave toward Needles. Keeley gazed off through sunglasses with one lens missing, his head tilted up, a contented look across his face. He pulled out a notebook and began to scribble away. It was only later that I realized he was writing backward.

Our correspondence had begun in earnest in May. His first words were: “I needed a break—I came from Peru and got beat up by the jungle.” This was a euphemism, it turns out, for being evacuated out of the Amazon by a plane owned by the Argentine oil giant Pluspetrol after showing up at one of the company’s outposts, anemic and demanding to speak with the president. Keeley had flown back to the States to recover from this latest ordeal, and set up shop in the Miami offices of a friend. Over the phone, his first call in more than a year, we settled on the rough outlines of an itinerary.

I wanted the full-immersion executive hobo experience. The plan was to start out West, where the rail yards are more open and the mountains more grand, and work our way east, to Chicago or Council Bluffs, or Texas, if it really came to that. We would buy clean clothes at Willy’s (Goodwill) and spend our nights at Sally’s (Salvation Army shelters), listening to sermons from born-again preachers in exchange for a hot meal and a warm shower and some yarns. We would exchange knowing nods in the jungle with our fellow hoboes, our partners in grime, and maneuver past the bulls using cunning and agility rendered dormant by the trappings of modernity.

Leaving the world behind is a major selling point, as well as a source of tension, for Keeley’s acolytes. Credit cards and wireless devices invariably find their way into the packs of the execs (a term he uses to describe basically anyone with a desk job), and from time to time one will desert the expedition altogether in search of a square meal and a hotel. But for the most part, they want to see how the other half lives.

“As a suburban middle-class kid, I had no understanding of things like poverty or homelessness or any of the things that would drive somebody to eat at a rescue mission,” says Arthur Tyde, an open-source software pioneer, recalling the first of several freight-hopping trips he’s taken with Keeley. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, there’s so much more bandwidth to the human experience than I’d ever been able to tune into before.'” The speculator Doug Casey told me about a highlight of his cross-country trek with Keeley: They were standing for a sermon at a mission one night when they found themselves in the middle of a knife fight. “The average person is like, ‘Oh, isn’t it dangerous? Oh, isn’t it illegal? Isn’t it gonna be uncomfortable?'” he says. “It can be dangerous, and it is illegal, and it is uncomfortable—and I recommend it highly.”

Tyde and Casey are emblematic of the type drawn to Keeley—masters of self-invention with a libertarian streak. After school at Michigan State University, Tyde moved to the Bay Area and founded Linuxcare, an early open-source software company, and began to dabble as a private investigator. Casey, an early goldbug, struck it big in 1978 with a book called The International Man, which encouraged readers to leave national borders behind in pursuit of wealth. (It became a bestseller in Rhodesia.) Now comfortably wealthy, Casey is pursuing his pet project, convincing heads of state—”generally military dictators”—to grant private corporations full economic control of their countries. The strongmen would take 10 percent of the profits, 85 percent would go to the people, and 5 percent would be publicly sold. He has never been given the green light, but his latest target is Mauritania. In such a world, trespassing laws are just another burdensome regulation to be cast aside.

A few days before I left for California, I had arranged to talk with Keeley again, but he asked to reschedule. “[I] forgot that tomorrow from early morn until 4pm time here i’m in court watching my friend attorney defend a homicide of a parrot who was witness to murder of human,” he wrote. “[T]he parrot’s name is Money and the high profile case is called ‘Money Talks’.” This is, I would discover, a trademark of a good Keeley yarn—largely true, in the same way that a steak salad is largely good for you. “Money Talks,” as Keeley dubbed it, wasn’t high-profile; the press never even noticed it. The defendant was accused of murdering another man in what prosecutors deemed a drug squabble. But there really was a parrot, and it really did die. As proof of the man’s pathological tendencies, the prosecution contended that he had murdered the victim’s bird too. Dan Factor, an attorney for the defendant, knew Keeley from his days on the professional racquetball circuit, and although they had not seen each other for 20 years, he had kept abreast of his old friend’s exploits. He told me that he was planning to leave behind the legal profession imminently, perhaps to open a shamanistic resort with his wife in Peru.

As I bided my time, I picked up a copy of Bo’s recent book, Keeley’s Kures: Alternative Practices From the Trails and Trials of a World-Champion Hobo-Adventurer. It’s a character study masquerading as a self-help book. At one juncture, we are informed that the author’s passion for science caused him to contract 35 percent of all ailments known to man, “including the obscure Hobo disease.” (This is a real thing, morbus errorum, caused by lice bites; don’t Google it.) He recommends reading backward and upside down, which he has trained himself to do, as a corrective to vision problems and neck pain. But most of his survival tips are fairly minimalist. The cure for altitude sickness is distilled water. The cure for bladder stones is distilled water. The cure for anxiety is distilled water. The cure for strokes is distilled water. In Keeley’s view, distilled water is a nectar of the gods, although other nectars can do in a pinch—he claims that, lost in the desert in triple-digit heat, he once survived by drinking his own urine. I made a note to pack distilled water.

Keeley greeted me at the Amtrak station in downtown Los Angeles with a smile and a handshake. “Are you a hobo?” he asked. He didn’t look like one. He’d come from the “Money Talks” trial in a crisp blue-and-white button-down shirt and was thin but healthy, with enough hair to be thankful for and a tattoo on his arm of a mouse with a smiley face and a teardrop, because “on the road, you’re always happy or you’ve got a tear in your eye.” Keeley watched as I sent a text message from the cab and quizzed me on how it worked. He uses Facebook in internet cafés but newer forms of technology flummox him—he struggled so magnificently to understand the Los Angeles subway fare machines that another passenger got off with him to help him purchase his ticket. I’d hardly known Keeley five minutes before he began unspooling his life story and telling me about his most generous benefactor, a renegade Connecticut hedge fund mogul named Victor Niederhoffer.

Keeley was the older of two brothers in a traditional Midwestern family. His father, who died in 2013, was a Navy engineer and a DIY enthusiast who built a two-person submarine in his garage. At the age of five, Bo finished his first painting. It was a freight train. He was a Boy Scout, an Episcopalian, and a productive student. When he arrived on campus at Michigan State as part of an accelerated veterinary program, he looked, one friend recalled, “like a young Republican.”

Granted all-night access to the gym through his work-study, he began experimenting with racquetball, and after submitting his exams, decided to forgo veterinary practice to play in the new professional league. He was a star, as these things go. Keeley was profiled in Sports Illustrated and published a how-to book that he says became the sport’s bible. He also offered glimpses of his future self—driving across the country, for example, with a seven-foot-tall stuffed rabbit named Fillmore Hare sitting shotgun. (The rabbit could wave to passersby when Keeley pulled a string that was tied to his hand; it was, he explained, a great way to pick up girls.) Keeley’s father questioned his decision to put his veterinary practice on hold and hustle racquetball. His mother was more philosophical. “He was in a mold,” she told SI, “and he stepped out of it.”

Before long, he walked away from professional racquetball too. “The famous Charlie Brumfield match,” he says. The Ali and Frazier of American racquetball were good friends who’d once even lived together in East Lansing, along with a Chuck Berry backup band called the Woolies. SI dubbed their friendship “the birth of modern racquetball.” But stylistically they were worlds apart. Keeley prided himself on conditioning. Brumfield was coldly manipulative. “He would play honestly, he would call his own skips, he would give me room to hit, and I did none of that fucking shit,” says Brumfield, now a lawyer in San Diego. At the fatal match in 1977, Keeley was leading when Brumfield excused himself from the court and disappeared. He returned, well-rested, an hour later to win. “It should’ve been a forfeit,” Keeley seethes, 37 years later. In an instant, racquetball’s Joe Frazier became racquetball’s Richie Tenenbaum, leaving the sport behind in search of his spirit.

Keeley’s next quest for reinvention hit a wall in the early 1980s when he fell in with a charismatic Salt Lake City martial arts instructor who claimed to be telekinetic. A journalist revealed the guru, James Hydrick, to be a fake; Hydrick was later revealed to be a child molester as well. (Total Catman points: one.) After they parted ways, Keeley hit the rails.

Being an international hobo is expensive, but fortunately for Keeley, the kind of people who excelled at racquet sports tended to move on to white-collar jobs when they were done. Before long, he got a boost from an old friend—Niederhoffer, a squash player whose renown on the court was eclipsed only by his prowess as an investment banker. They had bonded years earlier over shoes; Keeley, who wore mismatched red and blue kicks to tournaments, noticed Niederhoffer wearing mismatched black and white ones. As Keeley roamed the globe, they exchanged letters. During one of their regular racquetball meetups in New York City, Niederhoffer asked Keeley to work for him. Together, they devised a set of metrics, what Niederhoffer dubbed “low-life indicators,” that would measure the health of an economy by studying its most granular elements. The most common example would be the length of discarded cigarette butts—when times were bad, their theory went, bums would smoke them down to the filter. Other indicators included the amount of popcorn on the floor at skid row movie theaters and the amount of time a prostitute took to turn a trick. Keeley supplied this kind of economic intelligence to Niederhoffer as he crisscrossed the globe.

In return, Niederhoffer offered Keeley glimpses of his world, giving him the podium at the Junto, his monthly libertarian confab in New York City; hosting him at his palatial Tudor country estate; and, one year, inviting him to Thanksgiving dinner with George Soros at the Four Seasons. (Soros had enlisted Niederhoffer to manage hundreds of millions of dollars on his behalf; on the wall of his study, Niederhoffer keeps a painting of a red-Speedo-clad Soros greeting him on a beach.)

Then, in the late 1980s, he gave Keeley a new assignment: Travel the developing world, gathering materials for his collection of Titanic artifacts—and doling out cash to entrepreneurs, in return for 15 percent of any returns. Keeley’s plans hit a snag in Caracas, when he was almost slashed with a machete at a Chinese restaurant; the assailants took the money pouch he kept around his neck, the emergency wad sewed into his pants, and another stash in his back pocket. (Points on the Catman scale: four.) “You never have any desire for them, but they always happen,” Keeley says of his near-death experiences. The investor let him convalesce in a basement closet in his mansion, and then dispatched him on a new assignment: to travel to nine Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian nations, “investigate the state of the negative psychology of the country,” and report back. Relying on Keeley’s analysis of rickshaw tires and cockroaches, in 1997, Niederhoffer invested hundreds of millions of dollars in Thailand.

In July of that year, his Thai holdings lost 90 percent of their value. Shortly after the fall, Niederhoffer sat for an interview with a Japanese film crew. You can watch it now, if you want a glimpse of a man broken cleanly in half. In shorts and a sweatshirt, he takes the crew on a tour of his mansion, empty of many of the rare books and trophies that marked his opulent heyday. He looks as if he’s witnessed an unspeakable crime.

“How much did you lose?” the cameraman asks. On his sofa, Niederhoffer fidgets, pauses. Two seconds, three. “A staggering amount. A staggering amount. It’s too horrible touhuhto tell. But less than $100 million and well over $1 millionas they say in the US, somewhere between seven and nine fig-yuhz.”

“And what happened?” the interviewer asks. Niederhoffer blinks. Clearly, without a pause, voice perfectly still.

“Titanic.”

Niederhoffer retreated to his basement, where he spent hours playing with a train set by the stairwell cupboard Keeley once called home. He’s philosophical about the episode now. It was a mistake, yes. Hubris, sure. “In those days, we always wanted to be No. 1,” he told The New Yorker‘s John Cassidy in a sympathetic 2007 profile, and he had matured some.

When I asked Niederhoffer for his thoughts on Keeley, he demurred—twisted a knife, even. “He is usually not very generous in his estimate of others unless they are psychics or martial arts experts,” Niederhoffer emailed, referring to Hydrick. But what did it say about Niederhoffer that he bet his fortune on such a man? The truth is that Niederhoffer has a lot more in common with Keeley than just mismatched shoes and Ayn Rand (the speculator throws a party every year on her birthday and named his third daughter Rand). Niederhoffer was every bit the compulsive risk-taker the Catman was, every bit as disdainful of traditional ways, and every bit as confident in his capacity to outwit the system. He just played with a different kind of fire.

In time, Niederhoffer recovered, fell, and rose again. But the partnership was over. Keeley retreated to the desert, to the closest thing he has to a permanent residence: a trailer dropped into a 10-foot hole in the ground on the edge of California’s Chocolate Mountains Aerial Gunnery Range. Keeley calls it Scorpion’s Crotch.

Southeastern California is one of the emptiest places on the American map, and for generations it has been a destination for people who like it that way.1 It’s in the wastes of Imperial County that Christopher McCandless trained for his last march into the wild, and where an obsessive New Englander named Leonard Knight built a mountain of adobe and paint and dedicated it to God. These days, it’s where smugglers work in peace and outcasts go to disappear.

Scorpion’s Crotch is entirely off the grid, but about once every six months a stranger finds Keeley. It’s usually someone who has read his hobo writings and perhaps is a little dissatisfied with the American Way, and thus will make the pilgrimage down a sand-swept road in 110-degree heat to begin an adventure to be determined. Occasionally, Keeley’s hobo executives will drop by too. Tyde was so enthralled with the Keeley lifestyle he nearly bought a parched patch of land for himself. When he wanted to get in touch, he used to hop in a small plane and drop leaflets on Keeley’s property.

There’s something very Galt’s Gulch about the place, and when I raised this with Keeley, he confesses: Atlas Shrugged, he believes, is “hermetically perfect” because Ayn Rand wrote it without editors. Outside of pensions, a main source of income in the area is the United States military, which drops hundreds of tons of live ordnance on the Chocolates every year. When the bombing ceases, scrappers head into the mountains in dune buggies or armor-plated Volkswagen Beetles. Scrapping on a bombing range can lead to a year’s sentence if you’re caught—and an untold number of people have been killed or maimed—but a ton of brass or aluminum can go for $2,000 at the metal recycling center in San Diego.

Though Niederhoffer had chosen to rebuild his business without Keeley after the Thai collapse, he hadn’t cast him out of the libertarian financial clique entirely. Keeley continued to post regularly on Niederhoffer’s website, Daily Speculations, and his executive tour service was born in 2001, after he announced there that he was planning on riding the rails to Eris, the then-annual Aspen get-together hosted by the anarcho-capitalist Doug Casey (guests have included Ron Paul and the inventor of the Heimlich maneuver), and would anyone like to come? Keeley promised an “Outward Bound” experience, except instead of paying a few thousand dollars, he asked only that executives cover their own overhead.

“Bo’s very strict about that: You don’t pay him, ever,” says Nathan Janos, a data scientist from Santa Monica who caught a freight with Keeley after reading about him in the New Yorker article about Niederhoffer. In time, the list of “executives” who have taken the Keeley challenge have included a medical-device manufacturer; Tyde, the software guru; a New York real estate manager; a Toronto stockbroker; a San Diego therapist; a Florida geologist; and an emergency services coordinator for San Mateo County, California.

We completed our final prep work in the Orange County backyard of Steve Klett, the medical-device exec who once freight-hopped with Keeley to Tucson. I was beginning to get used to my traveling partner’s idiosyncrasies. He walks sideways down stairs, and glacially so, on account of the five-pound ankle weights on each leg, with his eyes sometimes closed and head tilted up like a turtle in the sun. He doesn’t wear underwear, a fact he volunteers freely.

As we enjoyed our final moments of suburban calm, I jettisoned a few books to make way for Keeley’s gift to me—a laminated zine, held together with a paper clip, called From Birmingham to Wendover: An Alternative Travel Guide to Cool Camping Places and Obscure Urban Hiking Trails Throughout the United States and Canada. The title is euphemistic; it’s a guide to railroad yards, instructing the reader on where and when trains will stop to change their crews, how tightly they’re policed, and even the location of old-fashioned diners. Passed underground from one trusted hand to another in hushed sort of tones, the zine is coveted by tramps in the way aficionados hunt certain kinds of bourbon. Its author is an almost mythical figure, a sort of hobo Santa. Keeley speaks of him with a reverence other people reserve for Keeley.

The rise of the executive hoboes marks a shift in Americans’ relationship with the iron road. At the turn of the last century, tramps attended “hobo colleges,” to learn philosophy and hygiene, and joined hobo unions, to ensure peaceful relationships with the railways. Early hoboes didn’t think of trains the way we think of cars, as something private; they thought of trains the way we think of highways, something to which everyone had a right. Ridership peaked during the Great Depression, when hundreds of thousands of workers camped in boxcars or squeezed between the wheels of rolling trains in search of work. But over the last 50 years, that transportation network has been remade. Trains are faster and harder to board. Boxcars are all but obsolete, and the post-9/11 security clampdown made rail yards harder to access.

The hoboes are different too. In 1998, Congress investigated the problem of railroad fatalities, and Jolene Molitoris, chief of the Federal Railroad Administration, suggested the high numbers of deaths stemmed from “the glamorization of hoboing.” The unemployed no longer ride freights from city to city, for the most part, although certain harvests, like potatoes and sugar beets, still attract migrant workers. Now it’s kids—anarchists, punks, or just homeless—and what Keeley calls “plastic people”—white dudes with cellphones and police scanners and credit cards who hit the road for a good time. That is, tramps like us.2

Klett drove us to Colton, about 60 miles outside of LA, rehashing his journey with Keeley the entire way and sounding for all the world as if he wanted to come with us, but for the job and the fiancee. We got out at a gas station, walked past a hobo encampment of young folks with dogs, and meandered down an overpass on the fringes of the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe railroad yard until we found ourselves in the humming, floodlit canyon between the trains. In a yard, Keeley is always looking to keep moving, hopping over and occasionally under containers, oil tankers, and gondolas to find the quickest and most comfortable ride. This can be exhausting, maddening even—especially after Keeley confesses this routine is partly for exercise.

At last we climbed into the front lip of a grain hopper, an upside-down trapezoid with sheltered cubbies at both ends, and somehow, amid the wheezing, screeching breaths of the mechanical beast, I drifted off. I awoke with a jolt as the train lurched forward, bracing myself with every track switch, curling tighter against the metal frames past every lit-up checkpoint I was sure would give us away. That first departure felt, I was sure, as close as one could get to reliving the ending of Argo. The train rattled through the suburbs and exurbs of the Inland Empire in the cool of dawn, and came to a final rest along a sandy wash 45 miles into the Mojave. We’d made it to Barstow.

Security is especially tight here because of the high quantities of military supplies that pass through. Janos, the MIT-educated data scientist, called his trip to Barstow with Keeley “the most intense experience I’ve had literally my whole life,” as they dodged bulls in jeeps with “infrared cameras and all that shit.”

We stalked the yard for hours, hiding out in groves of eucalyptus trees and walking for miles in 95-degree heat with 30-pound packs on our backs. It all seemed to come so easily to Keeley in his writings, but he had transformed into a hobo Patton in the desert, leading us on a cheerless series of false starts that felt more and more like training exercises. When our luck finally looked like it was beginning to turn, we got caught. “They’ve had me chasing you guys all day,” said the private security guard, not much older than 20, who nabbed us. He told us to walk a mile down the track, past the end of the yard, and catch a train on the fly by the Amtrak station like good hoboes—advice we promptly ignored. After walking parallel to the yard through sand dunes in the open sun, we shimmied under a small hole in the fence and back into the yard. The first train we boarded—the one I disembarked face-first—was headed in the wrong direction. The second one got us out.

For a moment, as our train rattled through the Mojave National Preserve, past the dancing shadows of Joshua trees and desert scrub, it clicked. We had outmaneuvered a yard full of bulls, dodged death, and now even the sun was on our side. But before long, the majesty gave way to the monotony of being trapped aboard a five-foot-long flatbed platform, fingers cramping up from clutching the latch of a shipping container to guard against sudden stops, our bodies weary and dehydrated. The train paused by the Colorado River around midnight and we stepped off. I was desperate for the bottle of Gatorade at the bottom of my pack, but Keeley barked to keep moving. Back on gravel for only a moment, we walked quickly up the train in search of a car with a platform deep enough to safely spend the night, climbed aboard, and were off once more. Nothing happens and then it happens so fast.

The next day found us idling through mountain meadows outside Flagstaff, pausing for anywhere from two minutes to two hours to let faster trains pass, or to switch crews, or for track maintenance, or, Keeley suggested more than once, because someone called us in. We inched across Arizona and the Malpas, nearly 100 miles of black volcanic rock that flows across the landscape like a river from hell, finally rejoining civilization 40 miles south of Albuquerque in a place called Belen. Where’s distilled water when you need it? I was out of provisions, and I was traveling with Boxcar Bear Grylls; if I didn’t speak up, we might never get off. When the train slowed to a stop, we made our escape. We climbed over a barbed-wire fence and eventually emerged at a Valero.

Keeley is an expert at adapting to unusual circumstances, but never fully groks normal ones. He insisted on staggering our entrance into the gas station, purportedly so as not to draw attention to ourselves, but stood out so much as he waited outside that a woman drove to McDonald’s and back just to bring him a bag of burgers. The stops at Willy’s and Sally’s, I was quickly realizing, were never going to happen at the breakneck pace we’d set, but we’d entered into a different world anyhow. Keeley had money but accepted the Big Macs gratefully, and the woman turned to me: “Would you like some too?” (I declined.)

The next three days were a slow descent into purgatory. We jumped on a piggyback—a flatbed car with a semi-truck on top of it—unsure of where we’d end up. The good news was that it was a hotshot, meaning it held high-priority cargo that other trains would have to make way for. We awoke in Clovis, New Mexico, passed Amarillo and Fort Worth, and crossed the Red River. The lights of Oklahoma City flickered by that night, as Keeley snored like a broken garbage disposal. Our relationship had frayed—conversation is difficult on a screeching train, earplugs are essential, and there was little I could do or say without falling victim to the Catman’s chronic second-guessing; he even refused to believe the Google map I consulted for our precise location. On Tuesday, I realized I’d only eaten four pieces of beef jerky since Sunday. Given the lack of a proper latrine, maybe this was for the best.

I’d reached my breaking point by Kansas City and prepared to make my exit. But the yards become more militarized the farther east you go, and this one felt like Normandy. Our options were to jump out of the train as it rolled and hope for an exit, or to get off when it stopped and almost certainly get caught. I had no outstanding warrants; a $200 fine seemed like a small price to pay to get a motel and shower up. Keeley wanted to keep going. Why waste money on a flight when you had a hotshot?

I’d learn that I wasn’t the only one to be worn down by Keeley’s proudly authoritarian approach. Tom Dyson, a British financial analyst who has ridden trains with Keeley in Mexico, Canada, and the United States, recalled that after wading across the Rio Grande to Texas, he had sought out a gas station to make a phone call to his wife. Keeley, “cranky as shit,” gave him five minutes, watched as he made the call, and when Dyson went over the allotted time, left him behind. “Bo’s just a weird guy, and I think he just understands things differently from other people,” he says.

Across Missouri, the lightning flashed brilliantly in the distance for hours, and when the skies finally opened up around midnight, sheets of rain pelted our car at 60 mph. The bivy sack wouldn’t close, and I began to panic. There was nowhere to get off, no way to stop, no way to ward off hypothermia except going fetal and praying for dawn. I thought back to what Steve Klett told me about his journey with Keeley, as we sat in his backyard just before I embarked on mine: “I’ve never been so out of control.”

Five days after we caught out of Colton, our ride terminated in a Chicagoland trucking distribution center called Willow Springs, and this time I led us out of the yard, past a smiling track worker, down a ravine, and across a four-lane road to a Dunkin’ Donuts, where we left puddles on the floor and Keeley bought a plane ticket on my phone. I paid for a cab to the airport and he answered my questions on the way, with a patience and charm I hadn’t seen since we embarked. He could flip that switch so quickly. “I’m going to Iquitos [Peru] and then, in September, to Baja,” he announced. For part of the last decade he has dreamed of extending the Pacific Crest Trail, which meanders down the Cascades and the Sierras, south through Baja to Cabo San Lucas. He had almost finished mapping it out: “I call it the Baja Loop.” When Keeley’s flight was called, he gave a firm handshake and a grin. My jump from the moving train in Barstow, he told me before he left, was worth one Catman point.

George Meegan, the British adventurer most famous for walking 19,000 miles from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic Ocean in the late 1970s, was sitting by the river in Iquitos, Peru, one sweltering night a couple of years ago when Keeley introduced himself and began to quiz him about the Darien Gap, an impenetrable tangle of swampy jungle that has thwarted land travel across Panama for centuries. Meegan compares Keeley to another Iquitos transplant, the real-life adventurer of the Werner Herzog epic Fitzcarraldo, who once transported a steamship over a mountain while exploring the Peruvian Amazon, before dying on the river at 35. “I rather think, Mr. Murphy, that he and I harken back to a previous age,” Meegan said. This, I discovered, was a common theme among those who associate with Keeley—the sense that they’ve lucked into an adventure with a work of historical fiction.

And I have to admit, seeing the West from the platform of a container car had its moments: There are things you can’t see any other way—graves of railroad workers in tall mountain meadows on century-old rights of way—and experiences that toughen you up psychologically. But there was something voyeuristic—even for a journalist—about tramping through hobo jungles hoping to catch a glimpse of an alcoholic or band of punks, dropping in on their world with a camera and a notepad as if I were after the snow leopard. “Are you familiar with Burning Man at all?” Tyde asked. “There are people who go to Burning Man because they want the experience, and then you’ve got like millionaire tourists who go because they can. I put that all in the same bucket. There are privileged people that go and do stupid things for the thrill of it, and I’m not really a fan of that.” His analogy surprised me because Tyde is a millionaire tourist; his most recent Facebook post, as of this writing, lamented the lack of wifi at this past summer’s Burning Man festival.

Keeley’s friends, many of whom go decades in between visits, press me for details when I tell them where I’ve been, and live vicariously through his exploits. It wasn’t necessary for the executives to live their entire lives as he did, to go Galt in one of the continent’s least hospitable places. It was enough for them to know that he had and they could. Meanwhile, they honored his ethos in small ways. Steve Klett, the medical-device VP, proposed to his girlfriend at a Mojave ghost town Keeley had first shown him. “He’s always in the back of my mind—always,” says Nathan Janos, who at Keeley’s advice turned down a six-figure salary and plans to travel around the world next year. “I hope he’s there for you too.”

A few weeks after we’d parted, Keeley had arrived in Puerto Maldonado on the Bolivian border and, about six months after being evacuated from the Peruvian jungle, began planning a new expedition up the continent with a “hoboette” named Boxcar Emily. Then he planned to return once more to Guatemala, for a ferry over the Usumacinta and a train ride north with the fall migration on La Bestia. “I was given a clean bill of health,” he wrote, “to walk the trails and hobo the Amazon tributaries.”

In the meantime, if I could convince my editors to send me to Peru, he had a story for me. One of the world’s largest gathering of shamans was coming to Iquitos, and Keeley promised to put me in touch with a man he called “the Johnny Appleseed of ahahuasca [sic]”—the psychedelic elixir best known for producing spiritual revelations and extreme fits of vomiting. The town was cheap and “full of riches for the curious gringo.” I politely declined.