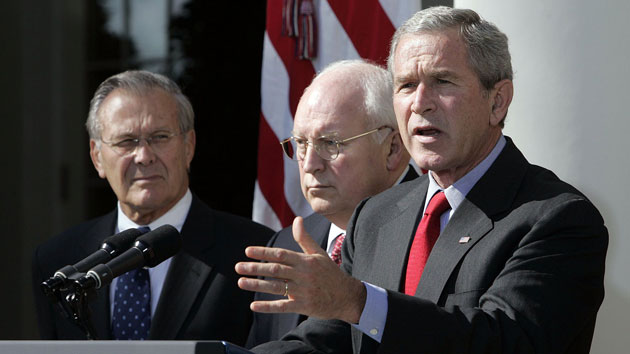

Pablo Martinez/AP

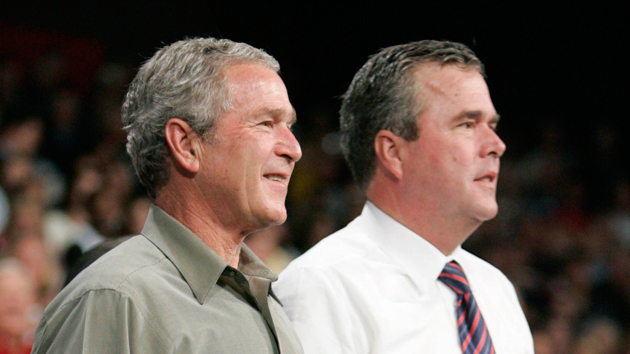

Last week, Jeb Bush stepped in it. It took the all-but-announced Republican presidential candidate several attempts to answer the most obvious question: Knowing what we know now, would you have launched the Iraq War? Yes, I would have, he initially declared, noting he would not dump on his brother for initiating the unpopular war. “So would almost everyone that was confronted with the intelligence they got,” Bush said. In a subsequent and quickly offered back-pedaling remark—on his way to saying he would have made “different decisions”—Bush emphasized that a main problem with the Bush-Cheney invasion was “mistakes as it related to faulty intelligence in the lead-up to the war.” And as his Republican rivals jumped on Bush, they, too, blamed bad intelligence for causing the war. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), insisting that he would not have favored the war (if he knew there were no weapons of mass destruction), commented, “President Bush has said that he regrets that the intelligence was faulty.” And former CEO Carly Fiorina noted, “The intelligence was clearly wrong. And so had we known that the intelligence was wrong, no, I would not have gone in.”

But here’s the truth Jeb Bush and the others are hiding or eliding: George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, & Co. were not misled by lousy intelligence; they used lousy intelligence to mislead the public.

Throughout the run-up to the war, Bush, Cheney, and their lieutenants repeatedly stated assertions to justify the war that were not supported by the intel. They also hyped or mischaracterized existing intelligence to bolster their case for war. The book I wrote with Michael Isikoff, Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, chronicles the elaborate Bush-Cheney campaign to misuse and misrepresent the intelligence. Certainly, there was some information within the intelligence community (which turned out to be wrong) indicating that Saddam Hussein was trying to revive programs to develop biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons. As the Bush White House was selling the possibility of war, the intelligence agencies did quickly produce a National Intelligence Estimate in October 2002 that said Iraq had “continued its weapons of mass destruction program.” But there was other intelligence and analysis—some of it mentioned in that intelligence estimate—casting plenty of doubt on this. In fact, on many of the key elements of the Bush administration’s case for war, the intelligence was, at best, iffy. Yet in this post-9/11 period, Bush and Cheney frequently declared there was no uncertainty: Saddam was pursuing WMD to threaten the United States, and, worse, he was in league with Al Qaeda.

Here are a few examples of how Bush and Cheney cooked the books:

-

In an August 2002 speech that kicked off the administration’s campaign for war against Iraq, Cheney asserted, “Simply stated, there’s no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us.” But earlier in the year, Vice Adm. Thomas Wilson, the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, had told Congress that Iraq possessed only “residual” amounts of WMD. There was no confirmed intelligence at this point establishing that Saddam had revived a major WMD operation. As Cheney made this claim, Anthony Zinni, a former commander in chief of US Central Command, was on the stage. He was stunned to hear Cheney say that Iraq was actively pursuing WMD. As he later recalled, “It was a shock. It was a total shock. I couldn’t believe the vice president was saying this, you know? In doing work with the CIA on Iraq WMD, through all the briefings I heard at Langley, I never saw one piece of credible evidence that there was an ongoing program.” In other words, bad intelligence did not cause Cheney to make this categorical, bold, and frightening statement. He just did it.

-

In September 2002, Cheney insisted there was “very clear evidence” Saddam was developing nuclear weapons: Iraq’s acquisition of aluminum tubes that were to be used to enrich uranium for bombs. But Cheney and the Bush White House did not tell the public that there was a heated dispute within the intelligence community about this supposed evidence. The top scientific experts in the government had concluded these tubes were not suitable for a nuclear weapons program. But one CIA analyst—who was not a scientific expert—contended the tubes were smoking-gun proof that Saddam was working to produce nuclear weapons. The Bush-Cheney White House embraced this faulty piece of evidence and ignored the more-informed analysis. Bush and Cheney were cherry-picking—choosing bad intelligence over good—and not paying attention to better information that cut the other way.

-

Cheney repeatedly referred publicly to a report that maintained that 9/11 ringleader Mohamed Atta had met secretly in Prague with an Iraqi intelligence officer—even though the CIA and FBI had dismissed this allegation. This is a damning example of Cheney citing discredited intelligence to score points. Intelligence experts had said there was nothing to this tale, but Cheney kept on mentioning the alleged Atta-Iraq connection to suggest Iraq was involved with the 9/11 attacks. The 9/11 Commission later reconfirmed that this report of a Prague meeting was bunk.

-

The Atta allegation was part of a wider effort mounted by the Bush-Cheney administration to link Saddam to 9/11. In November 2002, Bush said Saddam “is a threat because he’s dealing with Al Qaeda.” Weeks earlier, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had claimed he had “bullet-proof” evidence that Saddam was tied to Osama bin Laden. In March 2003, Cheney asserted that Saddam had a “long-standing relationship” with Al Qaeda. The intelligence did not show this. As the 9/11 Commission later concluded, there had been no intelligence confirming significant contacts between Iraq and Al Qaeda. Once again, Bush and Cheney were not being fooled by flawed intelligence; they were were pushing disinformation.

-

At a press conference at the end of 2002, Bush declared, “We don’t know whether or not [Saddam] has a nuclear weapon.” He clearly was suggesting that Saddam might already possess these dangerous weapons. Yet no intelligence at the time indicated that the Iraqi dictator had by then developed such weapons. The administration also insisted Saddam had been shopping for uranium in Africa, even though the intelligence on this point was dubious.

Bush and Cheney did not invade Iraq because they had been hoodwinked by bad intelligence. They claimed the intelligence was solid—when it wasn’t. And they made stuff up. Days before the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, Bush told the American public, “Intelligence gathered by this and other governments leaves no doubt that the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised.” Yet plenty of doubt existed. Intelligence analysts had registered uncertainty regarding all of the significant aspects of Bush’s case for war. Moreover, Bush and Cheney had for months tossed out a series of claims that were not supported by any confirmed intelligence.

The Iraq war at its heart was not an intelligence failure. Bush, Cheney, and their comrades were hell-bent on invading Iraq—not because of inaccurate intelligence, but because of their own assumptions and desires. The war did not happen because of bad intel. Consequently, asking whether the invasion should have happened knowing what is now known is an irrelevant exercise. For the Bush-Cheney gang, it truly did not matter what the intelligence said. They were not victims. They were the perps.