A recent study in the Journal of Real Estate and Finance Economics finds that black home loan borrowers are charged higher interest rates than their white counterparts—and that black women pay the highest rates of all.

The three finance professors who authored the study analyzed the mortgages and demographic characteristics of more than 3,500 households during the height of the housing boom—2001, 2004, and 2007—using the Federal Reserve’s triennial Survey of Consumer Finances. They found that on average, black borrowers were charged between 0.29 and 0.31 percentage points more in interest than whites, even after controlling for their debt and credit history.

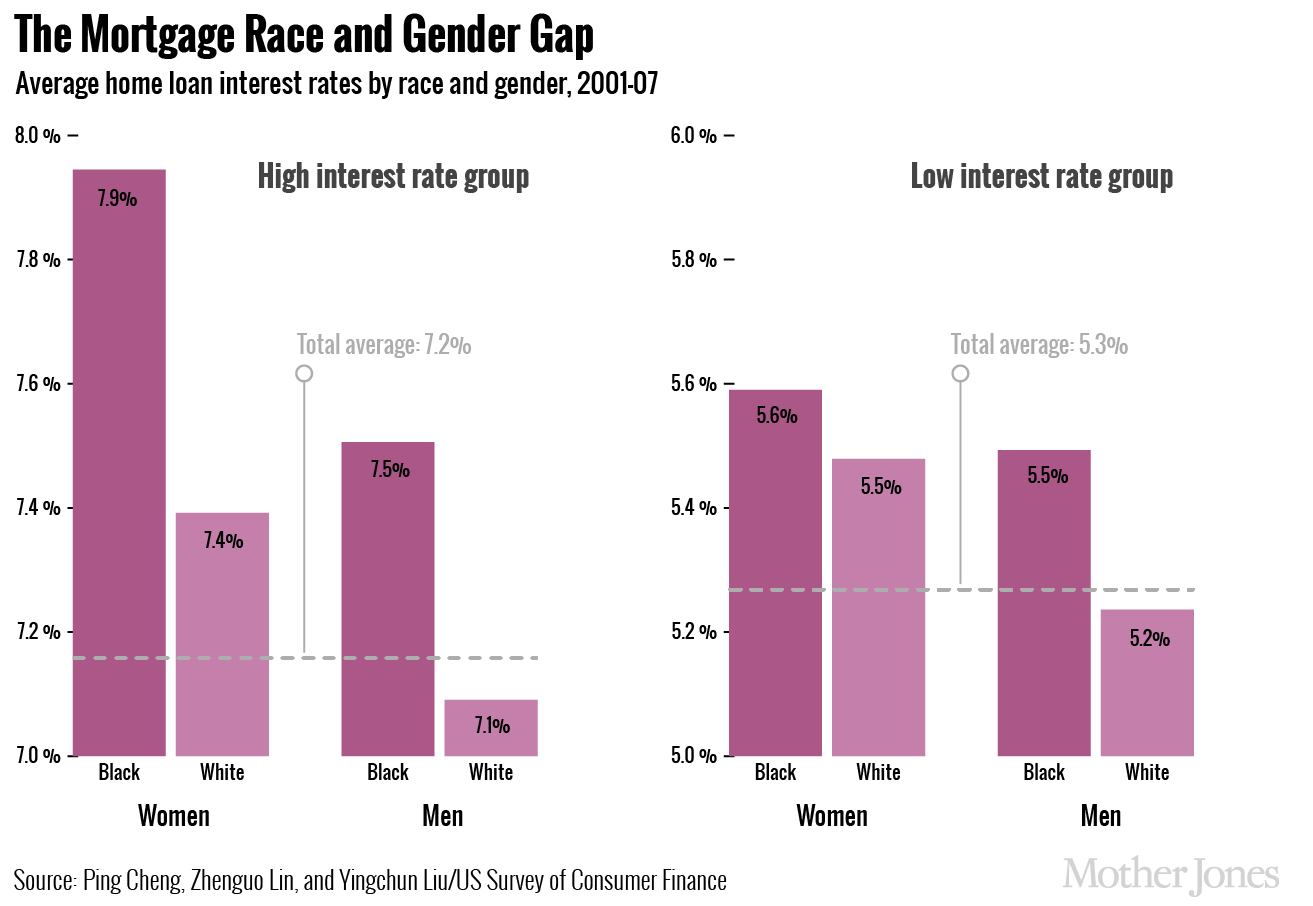

The racial disparity was most pronounced for subprime borrowers who couldn’t qualify for low-interest mortgages (the left side of the chart above), with black borrowers paying interest rates that were at least 0.4 percentage points higher than whites in the same group.

Within this group paying the highest interest rates, black women paid the highest rates of all, at an average rate of 7.9 percent. But a statistically significant disparity persisted even among those who paid lower interest rates (the right side of the chart), the study notes. In this group, black borrowers paid interest rates between 0.1 percent and 0.4 percentage points higher than their white counterparts.

Over at Quartz, Melvin Backman explains how these disparities translate into dollars: According to Freddie Mac’s mortgage cost calculator, a $200,000, 30-year mortgage would cost a black man about $3,000 more than a white man over the course of the loan. A black woman getting the same loan would pay nearly $9,000 more than a white woman.

The study adds to a body of research showing that black mortgage applicants are more likely to be denied credit than white applicants, and are more likely to be charged higher interest rates than whites. It also appears to confirm the racial disparities identified in lawsuits against several of America’s top mortgage lenders, including Wells Fargo and Bank of America’s Countrywide, which faced hefty payouts in a slew of discrimination lawsuits following the housing-market crash. The lawsuits had even prompted the Obama administration to set up a new unit in the Department of Justice’s civil rights division to deal with the caseload.

But the new study also suggests more granular disparities between black and white borrowers. Among black borrowers, for example, younger homeowners without a college education paid some of the highest interest rates. And among those paying higher interest rates, black women, who already face stiff obstacles to economic mobility, were likely to be charged interest rate premiums two to three times that of what black men were charged. While they do not speculate about the causes of these racial and gender gaps between borrowers, the authors conclude, “it is the more financially vulnerable black women who suffer the most.”