Frank Robinson, MLB's first African American manager, with former Seattle Mariners manager Lloyd McClendonAlex Gallardo/AP

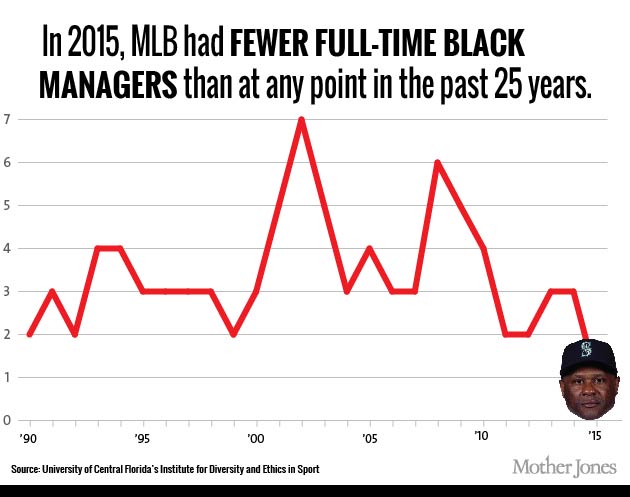

Earlier this month, the Seattle Mariners fired their manager, Lloyd McClendon, the only African American skipper in Major League Baseball. Now, for the first time since 1987, there isn’t a single black manager in the league.

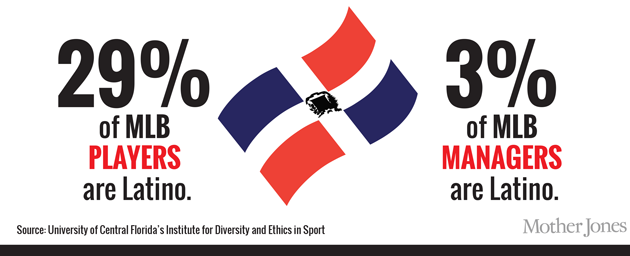

Just six years ago, in 2009, 10 teams employed black or Latino managers. And while 37 percent of coaches on major league staffs in 2015 were African American or Latino, roughly equal to the percentage of black and Latino big leaguers, there is currently just one manager of color: the Atlanta Braves’ Fredi González.

This is exactly the scenario that former Commissoner Bud Selig was trying to avoid when, in 1999, he sent a memo to league owners that required every club to consider minority candidates “for all general manager, assistant general manager, field manager, director of player development and director of scouting positions.” The progress made since Frank Robinson became the first black manager in 1975 had started to fade; when the “Selig Rule” went into effect, three managers of color led major league teams. Three years later, though, there were 10.

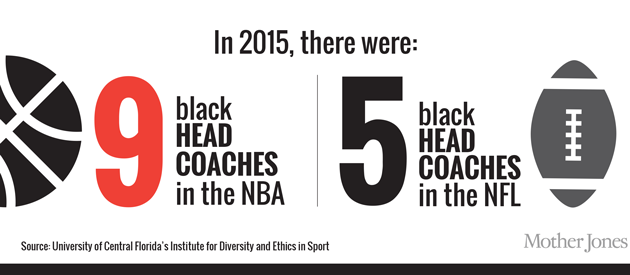

Richard Lapchick, executive director of the University of Central Florida’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, once lauded the Selig Rule and the NFL’s so-called Rooney Rule as “dynamic forces of change” for front offices. More recently, though, both initiatives have been criticized for not doing enough. At least the Rooney Rule requires NFL franchises to interview minority candidates; the Selig Rule, on the other hand, says that teams merely must include minority candidates on their lists of potential hires and submit those lists to the league office. (During Selig’s tenure as commissioner, which ended before this season, there were always at least three big-league managers of color.)

Earlier this year, Commissioner Rob Manfred sent out a notice to owners reiterating the league’s stance, hours before the Milwaukee Brewers fired manager Ron Roenicke. The team hired Craig Counsell to take over the team the next day without conducting a formal interview process. The move raised questions about the league’s ability to hold teams accountable for following through on its hiring recommendations.

Manfred later told the New York Times that the league would look at the rule, noting that he tried to get a commitment from teams that hired interim managers to conduct a full search after the season ends. (Although bench coach Dave Roberts served briefly as interim manager for the San Diego Padres this season, he has not interviewed for the full-time position. He’s reportedly a finalist to replace McClendon in Seattle, however.)

Baseball’s diversity problems go beyond the manager’s seat, of course. For the last three decades, the percentage of African Americans in the big leagues has declined (though that figure has remained relatively flat at 8.3 percent in the last five years, leaving a pinch of hope). And while the Selig Rule was intended to surface more minority candidates for front-office positions, a mere 13 percent of general managers are people of color.

Major League Baseball will continue touting its international pipeline and its efforts to bring the sport back to kids in America’s inner cities. But for now, managers of color may continue to feel, as McClendon told the New York Times in July, “like you’re sitting on an island by yourself.”