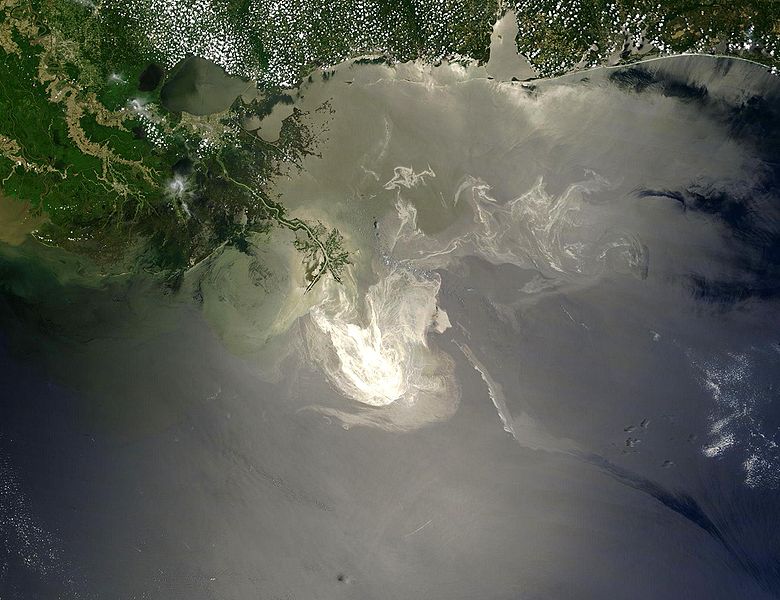

Photo courtesy NASA

BP has dumped about 10,000 gallons of dispersants onto and under Gulf waters in the past month. The idea being that the dispersants will break the oil down into small enough globs for natural marine microbes to clean up.

We know these dispersants are toxic. In lab tests, Corexit—BP’s favorite—kills shrimp and fish. Now David Valentine, a biogeochemist at the University of California Santa Barbara, warns the stuff may be riskier than just its toxicity. Corexit may undermine the microbes that naturally eat oil.

Some of the most potent oil-eaters—Alcanivorax borkumensis—are relatively rare organisms that have evolved to eat hydrocarbons from naturally occurring oil seeps. Valentine tells Eli Kintisch at Science Insider that after spills, Alcanivorax tend to be the dominant microbes found near the oil and that they secrete their own surfactant molecules to break up the oil before consuming the hydrocarbons. Other microbes don’t make surfactants but devour oil already broken into small enough globs—including those broken down by Alcanivorax.

What we don’t know is how the surfactants in Corexit and its ilk might affect the ability of Alcanivorax and other surfactant-makers to eat oil. Could Corexit exclude Alcanivorax from binding to the oil? Could it affect the way microbes makes their own surfactants? Could Corexit render natural surfactants less effective?

The National Science Foundation has awarded Valentine a grant to study the problem.

BTW, experiments from the 1980s done on wildlife in the wild (nesting Leach’s Storm-Petrels on Grand Island off Newfoundland) found that birds exposed to crude oil or to Corexit lost more eggs and chicks than did control birds. Of the adult birds that survived contamination with higher levels of oil or Corexit, many fewer returned to breed the following year than did control birds—intimating their exposure was lethal in the long run if not the short run.

(If you appreciate our BP coverage, please consider making a tax-deductible donation.)