10-year-old Zoe Oden on Zoom.Mother Jones Illustration

The first thing I notice when I log on is Ms. Washington’s purple witch hat. Just a few Zoom squares away, there’s a background of a spooky Halloween scene, complete with a Jack-o-Lantern scarecrow and a glowing crescent moon. It’s festive and sweet, but far from the normal Friday before Halloween for the 18 fifth graders led by co-teachers Ms. Washington and Ms. Vega.

Later in the day, during “Fun Friday,” the students share pumpkin art. During lunch, they watch Hotel Transylvania.

Still, it is just another day at virtual school, the teachers moving fluidly between online platforms in an interlocking digital dance. Zoom for video chat. Google Classrooms to share docs and quizzes. Benchmark for reading. Khan Academy and GoMath for math. Videos embedded in Google Slides.

I am logged on as a guest of Zoe Oden, a 10-year-old who loves being in the middle of the action. Her dad built her a desk in the dining room—it’s a vantage point from which she has a direct line of sight to all the most trafficked areas of the house: the kitchen table, the backyard, the hallway, and the living room. “Everybody walks by and says hi,” Zoe tells me with a smile.

Seeing Zoe in class, it is no surprise she’s a straight-A student. She is usually one of the first ones to raise her hand. When her group is down a student to play a part in a scene they are reading out loud, Zoe volunteers to read for two parts, which she does with feeling. In math class, she explains so clearly why decimals need to be rounded to the tenth place that it sounds like she could have been reading straight from a textbook. When the teacher asks the students about some activities they like that don’t depend on being plugged in, Zoe says that she likes to sit outside and read a book. Her favorite book is Michelle Obama’s Becoming.

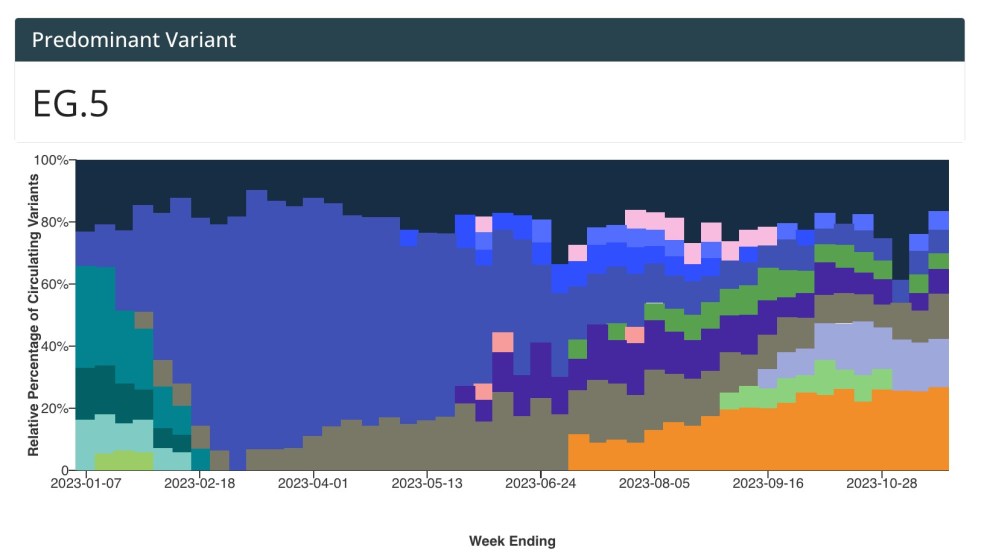

Zoe and her four siblings all attend AIMS, a K-12 college prep charter school in Oakland, California. They have been doing virtual school from home since mid March. With coronavirus cases on the rise across the country, there’s no end in sight to the virtual classes like those I attend on Friday.

I am not totally sure what to expect when I join in; much has been written about how uneven virtual learning has been so far, and complicating matters more, Oakland has been experiencing rolling power blackouts. But it is surprisingly…smooth and hands-on. Independent work time is interspersed with lectures, quizzes, and group activities.

Zoe Oden raises her hand on Zoom.

The kids keep themselves muted unless they are speaking. They hold their hands up in the Zoom screen when they want to speak. They nod or give thumbs up when their teacher asks the group a question. Occasionally someone’s little sibling will toddle into the background. Sometimes the internet will cut out and the teacher will lose a student’s video, or a student’s voice will sound glitchy and robot-like when they try to answer a question. By the end of the hour-and-a-quarter classes, some kids start to lose concentration. One starts eating a snack. Then, just in time, class adjourns for a ten-minute break.

When Zoe first started attending AIMS, her mom drove Zoe and her two older siblings about two to three hours to school each way, depending on the Bay Area traffic. But for Zoe’s mom, who used to be a teacher at the school and is now a parent coordinator at AIMS, it felt worth it. She loves the fact that her five kids could all go to the same school because it’s K-12. She was impressed with the school’s academics. And, importantly for Zoe’s parents, the school is diverse. Zoe and her siblings are African American and Latino.

“I have a lot of diverse friends and everybody’s nice,” says Zoe. She tells me she feels supported at school. “Everybody cares.”

AIMS was founded in 1996 as a charter school for American Indian children. The original curriculum included classes like basket weaving. Over time, the school expanded its demographics and became one of the most diverse schools in Oakland. It started climbing the Great Schools charts in academic performance, especially among students from underserved populations. Like public schools, AIMS operates with state and federal funds and is tuition free, but it’s exempt from public schools’ curriculum. The elementary school has about 440 students, with about 80 fifth graders split across three classes. This year, there were 75 kids on the waitlist to get into AIMS’ kindergarten class. This is all to say that while observing on Friday, I got a window into one remote learning experience; AIMS may not necessarily be indicative of broader experiences in Zoom learning. When schools closed last March, AIMS administrators were quick to purchase online programs like Benchmark, Learning Farm, Quill, math using Go Math!, and Seesaw. They converted their textbooks to a digital library. They secured Chromebooks and hotspots for families who needed devices and internet connections. This year AIMS purchased 100 new Chromebooks for a one-to-one Chromebook-student ratio.

And it’s worked well so far for the Odens. Zoe’s mom describes the process as having been pretty seamless. While living in a house with five kids can get chaotic—I can attest to one lunch-time converasation during which little voices chimed in from the background, and Zoe’s little brother wandered into the Zoom frame randomly wearing a sombrero—but overall, Zoe and her siblings have gotten a routine going. Her two teenage siblings work upstairs in their rooms, while Zoe and the two little ones work downstairs with their mom. When Zoe has to speak in class, she just lets her mom know that she’s unmuting herself. Her mom usually works right next to her little brother, who is in first grade. The kids use their parents’ bedroom and close the door when they need to take a test.

Just like virtual learning at AIMS is probably not typical, Zoe isn’t exactly typical either. She has a sunny disposition and the tendency to see the glass half full. She actually likes being the middle child because she gets to experience being both an older kid and a younger kid. Her favorite subjects are Mandarin and math, though she finds decimals a little tricky sometimes. Least favorite subjects? She doesn’t have any. When I ask her if she prefers at-home or in-person schooling, she tells me she prefers them both. She misses seeing her teachers and friends and school administrators in person. She misses being around the front desk, where everybody hangs around and talks, and the two front-desk receptionists who used to say hello to her every morning.

But, she admits virtual schooling has its perks. She notes the quick commute. Plus, she says, “For virtual school you can sit in your own house. You can also wear whatever you want,” she tells me, adding for emphasis: “Whatever you want.”

On Halloween Friday, that means Zoe is wearing a black hoodie. She was going to dress up as a cheerleader this year, but since trick-or-treating is not pandemic-friendly, she decided not to bother with a costume. On actual Halloween night, normally Zoe and her siblings would get dressed up in costume and go trick-or treating all together with their parents, using pillow cases as candy bags, and hitting up the houses in their neighborhood before coming home and beginning to trade. “Every year, as soon as we get home from trick-or-treating, we open our bags and say, ‘Hey, I’ll give you my gummy bears for your Reeses,'” says Zoe. She is always on the lookout for Skittles, Baby Ruths, and Ferrero Rochers—her favorites.

But this year, like class, and like so many things, Halloween will look a little different in the Oden household. Zoe is staying home with her siblings, eating candy, and watching Halloween movies. Casper the Friendly Ghost, The Addams Family, and Hocus Pocus are on the docket.