Mother Jones illustration; Getty

In December 2016, Forbes put Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick on its cover. “Super Uber,” a headline declared. “The most valuable startup ever isn’t content to be the Uber of Uber. How the $68 billion juggernaut is about to change the way everything moves.”

The story opened with Kalanick pacing about a conference room. He was not just some “bro” or “douche.” As “jam sessions” like this one revealed, he had a “special sauce.” This was Uber’s actual genius: A PR machine that could transform six men listening to a boss in gray chinos into something almost mystical.

Two weeks before, Hubert Horan, a little-known expert on the airline industry, wrote a blog post for an equally little-known website, called Naked Capitalism, that went in a different direction. Horan’s thesis was that Uber was a tremendously unprofitable, inefficient, and not particularly innovative company that would make money only if it bought its way to an unregulated monopoly.

Kalanick on the cover of Forbes in 2016.

Forbes

Compared to the Forbes piece and many others like it, Horan’s article was a fiduciary root canal. (“There is no simple relationship between EBITAR contribution and GAAP profitability,” reads part of one sentence.) The goal was to show that Uber was hugely unprofitable and how, in the event that it did succeed, profit would come from hurting consumers and overall economic welfare by cornering the taxi market.

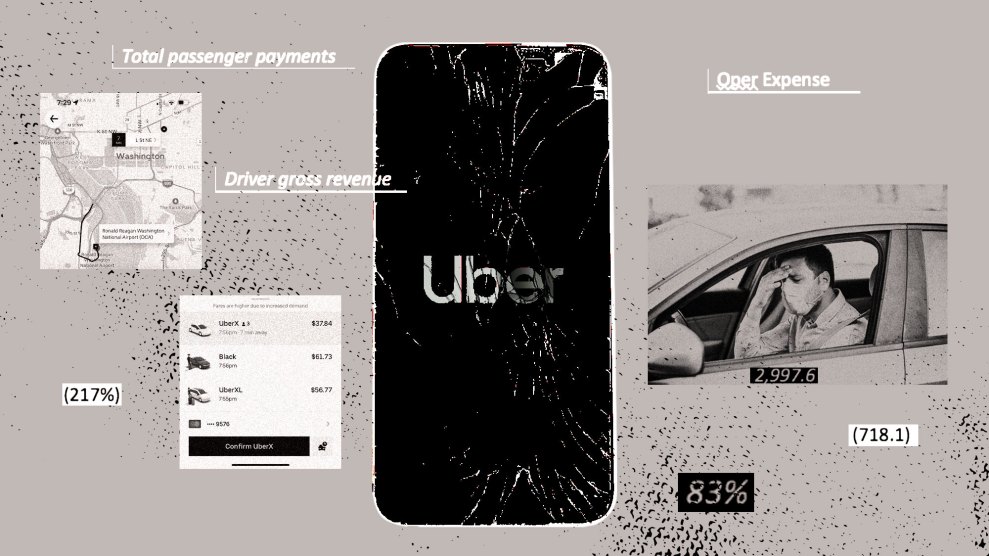

Horan, who started consulting in the airline industry after getting his MBA at Yale in 1980, has now written 26 more installments of his Uber series. When combined as PDFs, the posts run 193 pages. They reveal him to be much more a Cassandra than a crank. Uber has lost in the neighborhood of $28 billion since it launched in 2009. Its rides now cost far more than cabs in many major cities, its workers are as exploited as ever, and taxi drivers face massive debts, partly as a result of its business practices. Consumers, meanwhile, are shocked to learn what the rides investors have been subsidizing actually cost.

In Uber’s telling, the dynamic is about to change. In a late September SEC filing, CEO Dara Khosrowshahi announced that the company was reaching an “important milestone” after running “more profitably than ever before” in the third quarter of 2021, which ended in September. As the beginning of another Forbes headline put it: “Uber Poised To Turn A Quarterly Profit.” It will likely officially announce this newfound profitability during its quarterly earnings call on Thursday.

But Uber has not actually become profitable. Instead, as the company stated in its September SEC filing, it believes it will be profitable based on its own “adjusted” formula, which excludes 13 categories the company does not like to count, such as stock-based compensation and the money it’s spending to respond to the pandemic.

Not surprisingly, Uber’s adjusted profit formula is a longtime bugbear of Horan’s. As he has written, the in-house tool gives the company the “ability to manipulate how much (fake) profit it earned each period, and allows it to mislead investors about how fast Uber is approaching profitability and how far it has to go.”

Horan says he’s occasionally seen other companies use “these totally bullshit accounting games.” But he adds they are the equivalent of a neon sign reading “Danger! Management Isn’t Trustworthy—Don’t Invest Here!” In 2020, for example, Uber reported a net loss of $6.7 billion on $11.1 billion of revenue. But according to the company’s adjusted profit measure for the year, it came up $2.5 billion short. More than $4 billion in losses were accounted away.

Uber spokesperson Noah Edwardsen said via email that he couldn’t respond to questions about Uber’s profitability before the Thursday earnings call. He noted that Uber reported net income of $1.1 billion in the second quarter of 2021. But that was because the value of its investment in the Chinese ride sharing company Didi increased, not because its own operations turned a profit.

But the real Uber story to Horan is not that one company is bad at turning a profit. As he wrote in an email to me, it’s about what we can learn when a company “with massive multi-billion dollar losses, hellacious internal problems and no competitive advantage over incumbents” is “able to take over an entire industry, nullify laws in hundreds of cities and establish a powerful reputation as a highly innovative and successful company.” It reveals much more fundamental problems about the ways our economy allocates capital.

This isn’t just an Uber problem. For Horan, the advantage of writing about Uber is that more important things like health care immediately polarize people. Taxis don’t. His goal is to suggest that if one company could so easily get billions it shouldn’t have gotten, then “the problems beneath this tip of the iceberg might be really serious.”

It’s also a story about how public relations get the best of us again and again. WeWork convinced investors and journalists that an office space company would make billions because it had the “soul of a kibbutz.” Juicero hawked a juicer that couldn’t juice. Theranos, you know already. Uber is still getting by. Profit is just around the corner. Maybe it will come from Postmates, the food delivery app it acquired last year? Or from Drizly, the alcohol delivery app it acquired this year? There is money to be made in hope.

Horan wasn’t the first to call bullshit on Uber—he credits Sarah Lacy of the tech news site Pando and the Financial Times’ Izabella Kaminska with getting there first—but he has wound up being the most thorough. Like so much tech coverage, stories about Uber often have stuck to the personalities. First, there were the stories about Kalanick taking on supposedly evil taxi monopolies. Then came the ones about his bad behavior. After Kalanick was pushed out, a new wave of coverage focused on how his replacement, Khosrowshahi, would adultify headquarters.

These stories tended to treat future profitability as a fait accompli. If Uber couldn’t make money ferrying people around with human drivers, then it surely would once its cars drove themselves. When Uber sold off its self-driving car division last year after losing billions on it, stories framed it as a way for Uber to focus on profit, even though the self-driving cars were originally sold as the path to profitability.

Horan, who became suspicious of the overwhelmingly positive coverage Uber initially received, took a much more basic approach when he started looking at the company in 2016. Uber was a taxi company, so he started researching the economics of taxi companies. What he learned about the industry fit with everything he knew from decades of transportation consulting: Companies that move people and things make money by closely controlling their workers and physical assets. UPS doesn’t tell its drivers to deliver packages whenever they feel like it, nor does it have them repair trucks at the local mechanic.

Another problem he saw was that taxi companies had never been particularly profitable. When they did eke out narrow margins, they did so through poor pay and keeping operating costs low. They didn’t spend hundreds of millions on marketing and hiring alumni of presidential administrations. And unlike other Silicon Valley startups, Uber didn’t have economies of scale to exploit. There always needs to be a fixed ratio of drivers to passengers, something that isn’t true of coders to TikTok users.

As is now more widely understood, Uber’s best hope for getting around these problems was to get investors to subsidize rides so that it could evade longstanding labor protections, kill off taxi companies, establish a monopoly, and then jack up prices beyond what the cabs used to charge. Uber was a disruptor—just not the kind it was made out to be. As Horan wrote in 2016, “It is disrupting the idea that private wealth creation requires the development of companies with superior products and superior efficiency than existing competitors.” But Uber has not yet succeeded in creating a monopoly. Yellow cabs in New York City are even gaining market share again.

After Thursday’s earnings call, Horan will have a 28th chance to explain why Uber is still not actually profitable. Like it has for the past five years, Uber will presumably ignore him. Business blogs will ask whether now is the time to buy its stock.