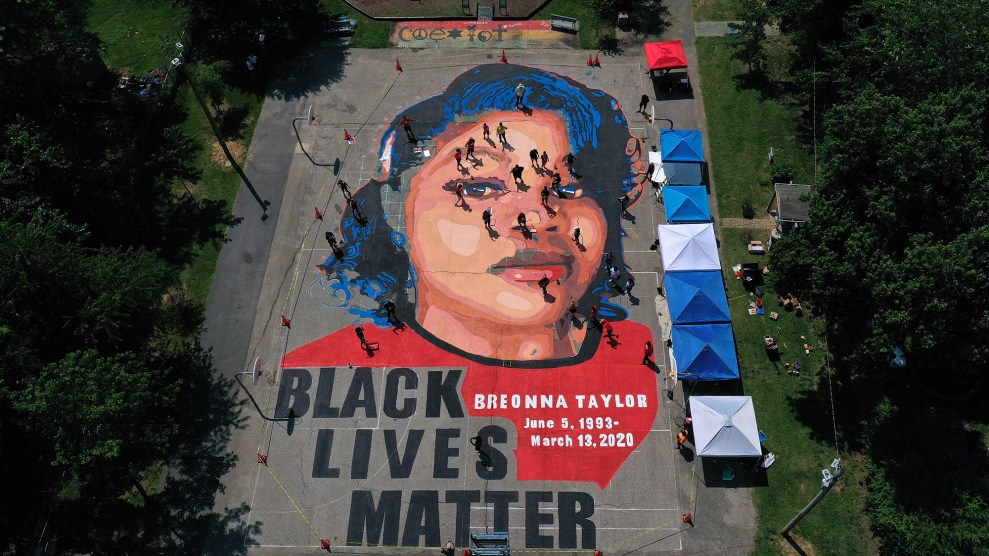

A large-scale ground mural of Breonna Taylor is seen being painted in Annapolis, Maryland, in July. Patrick Smith/Getty

One year ago today, Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black hospital worker, was shot dead by police in her home in the middle of the night. The Louisville, Kentucky, officers barged in around 12:40 a.m., looking for drugs and finding none. In the months afterward, Taylor’s name became a rallying cry at racial justice protests around the country as activists called on authorities to defund police, prosecute the officers who killed her, and put a stop to lethal raids of Black families’ homes. In her hometown, people took to the streets for more than 150 days straight.

But how much has actually changed? One year later, the racial justice protests go on, yet the protesters’ demands remain largely unmet. Three police officers lost their jobs because of their roles in the raid, but none were prosecuted for killing Taylor. The only officer now facing criminal charges is under investigation for firing his weapon into a neighboring home, damaging some walls. And while some big cities cut their police budgets during the pandemic, leaders in Louisville voted to slightly increase funding for local police after Taylor’s death.

Taylor was hardly the only Black woman who had police barge into her home over the past year. Such raids are common, according to Peter Kraska, a professor at Eastern Kentucky University who is a national expert on police tactics. He estimates that tens of thousands of residential drug raids now occur every year with little to no warning for the civilians inside—officers storm in unannounced or knock and enter forcefully seconds later. In an ACLU study of more than 800 SWAT team deployments, most of which involved search warrants, 42 percent of the people on the receiving end of the search-warrant raids were Black, and another 12 percent were Latino.

Very rarely do botched raids attract the level of attention Taylor’s case did. In fact, most fly under the national radar, like the case of Chicagoan Sharon Lyons. One evening in February last year, Lyons was in her kitchen when her front door flew off its hinges and more than a dozen police rushed inside with guns and flashlights. Her 30-year-old son, Julius, who has autism, ran toward her in terror, and her 4-year-old granddaughter screamed from the bedroom. The girl said police pointed guns at her. They’d raided the wrong address.

Six months later, Nashville resident Azaria Hines had fallen asleep on her sofa without clothing on after working a late shift. She awoke to banging on her door. Realizing it was the police, she told them she would let them in after she was dressed; instead, the cops knocked her door down with a battering ram, pointed guns at her as she stood naked, and refused to let her put on a shirt as they searched for evidence related to a stolen vehicle. Her 15-year-old cousin and 3-year-old nephew woke up and were ordered outside. Wrong address again.

Other poorly executed raids have killed or injured civilians. Last September in Jacksonville, Florida, Anthony Gantt and Diamonds Ford awoke to the sound of shattering glass. Fearing a burglar, Ford fired at one of the officers breaking in and called 911 to report a home invasion. The cop survived. Now Ford and Gantt face charges of attempted murder and marijuana possession. A similar scenario played out last month, when SWAT officers in Mobile, Alabama, busted into 18-year-old Treyh Webster‘s home early in the morning, looking for weapons. The officers said one of them shot and killed the teen after he fired a gun, but Webster’s mother, who was shot in the foot, said the cops didn’t knock and the family thought they were intruders.

Just over a year ago, one day before Taylor was killed, a SWAT officer in Potomac, Maryland, shot and killed 21-year-old Duncan Lemp and wounded his girlfriend during a predawn raid of his parents’ home. Police said they suspected that Lemp, a computer programmer, possessed weapons illegally and was part of a militia. They shot at him through a window, they said, because he got out of bed and grabbed a rifle. The cop who killed Lemp wasn’t wearing a body camera—and wasn’t prosecuted, either. The family said police opened fire while Lemp was asleep, and then charged into his room and stomped on his neck.

As the death toll mounts from problematic raids, reform attempts are underway. In Kentucky and other states, activists are pressuring lawmakers to end or restrict no-knock and quick-knock raids that have killed Taylor and others.

Last June 11, Louisville’s Metro Council voted unanimously to ban no-knock search warrants, which the officers who shot Taylor possessed, and which allow police to bust into a home without announcing their presence in advance. That same day, Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky said he would file the Justice for Breonna Taylor Act to end no-knock raids by federal law enforcement. Democrats in Congress are pushing for similar changes as part of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which would compel federal officers to knock and announce themselves before conducting drug raids.

Last month, the Kentucky Senate also approved a bill that would ban no-knock warrants, except when a judge decides that knocking will endanger lives or allow the suspect to destroy evidence. At least 23 cities and 26 states are considering bills that would ban or restrict such raids, according to an analysis by Kraska and Campaign Zero, a police accountability nonprofit.

Despite such reform efforts, even a blanket ban on no-knock warrants won’t stop police from making the same kinds of mistakes that led to Taylor’s death. Police more typically obtain standard search warrants, which require them to knock and announce themselves before entering, but that’s hardly any better, since most departments don’t dictate how long officers must wait after knocking, or their policies include exceptions that let police rush in fast. Police conducting a raid often barge in just after knocking to maintain the element of surprise. This may make the situation safer for them, but it is just as dangerous as a no-knock warrant for everyone inside.

During the 1990s, Kraska embedded with SWAT teams for two years, and witnessed about 65 police raids. Most involved standard warrants, but the officers usually went in very quickly. He saw children handcuffed, homes ransacked while the family watched, dogs shot, and innocents hospitalized. “We all get caught up in who died and we tend to forget we’re talking about squads of government officials breaking in and ransacking people’s homes on a routine basis.”

The cops who killed Taylor say they knocked, but most of Taylor’s neighbors didn’t hear it. Her boyfriend, who said he feared an armed invasion, fired a gun at one of the officers, who, along with his colleagues, reciprocated with more than 30 rounds, killing Taylor. (Charges against the boyfriend were dismissed.)

Kraska and other activists are encouraging politicians to look at the problem more broadly. Ideally, he says, the laws should restrict regular warrants, too. Campaign Zero’s model legislation requires police to wait at least 30 seconds after knocking, and prohibits nighttime raids, when people are sleeping and more likely to wake up confused and thinking that bad guys are breaking in. Some lawmakers are considering bills that would limit the types of excuses cops can give to justify barging in immediately—they argue that the fear of evidence being destroyed isn’t a sufficiently compelling reason to put civilian lives at risk.

It’s also important for police to document their raids, Kraska says. Lawmakers should enact body-cam requirements, and data-collection mandates that compel police brass to track the number of times their officers busted into homes, whether kids were present, and what casualties resulted. Some states, including New York, are pondering such restrictions on regular warrants.

Other state leaders are getting pressure in the opposite direction. Kentucky lawmakers are now considering a bill that would make it a crime to insult police during protests. The legislation, clearly aimed at Black Lives Matter protesters, is sponsored by a retired police officer. The bill would allow for up to three months’ behind bars, a fine, and temporary disqualification from public assistance benefits to anyone who “accosts, insults, taunts, or challenges a law enforcement officer with offensive or derisive words,” or makes “gestures or other physical contact that would have a direct tendency to provoke a violent response from the perspective of a reasonable and prudent person.” The bill passed out of committee recently. It’s “just surreal, Orwellian language,” says Kraska, who, along with the ACLU of Kentucky, believes such a law would violate the First Amendment.

Taylor’s family, meanwhile, still longs for justice. Her mother, Tamika Palmer, recently told NBC’s Today show that throughout the family’s whirlwind of grieving, filing legal petitions, protesting, and watching most of the involved officers escape criminal charges, it has been hard to keep track of all the time that’s passed—a full year since the police took her daughter’s life. “Nobody’s been held accountable,” she said. “I don’t even know the difference in the days anymore.”