An empty picnic area.Tracy Barbutes/Zuma

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

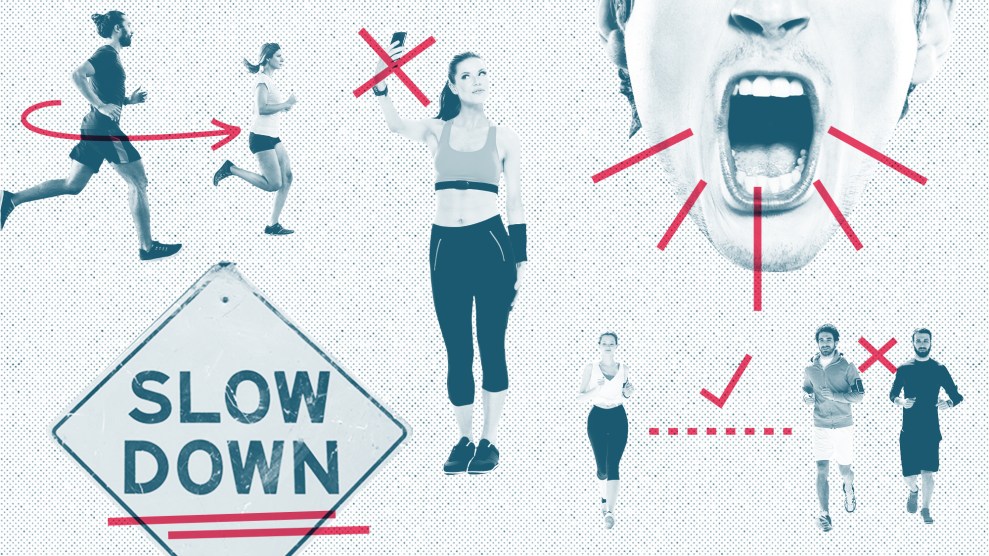

As the COVID-19 pandemic takes hold across the country, residents are called to practice public health measures in our parks and the outdoors. This includes practicing social distancing and avoiding outdoor recreation towns that cannot afford the risk of caring for infected visitors.

The message has been straightforward: Stay away from these towns and public lands; if you’re irresponsible, we’ll close the trails and parks down. At the same time, suggestions and guidelines are offered on how we can still get outdoors safely: Stay close to home, engage with nearby nature, and hike in your neighborhood. These instructions are necessary, but they are based on the assumption that everyone has the privilege of outdoor access and will be affected the same when it is taken away.

As the founder of Latino Outdoors, a Latinx-led organization that connects the diversity of Latinx communities with the outdoors, and someone who has spent years working to make the outdoors a more equitable space, I think it’s important to keep frameworks of equity and inclusion in mind, especially during times when inequalities are being amplified. If we don’t, we risk perpetuating existing inequities that have a real cost in terms of the health of communities of color as well as others who have historically lacked equitable access to the outdoors.

Across the West, people of color have long experienced unequal access to outdoor spaces. In a 2018 study, researchers David Scott and KangJae Jerry Lee note data from the National Park Service Visitor Services Project showing that Hispanics and Asian Americans comprised less than 5 percent of visitors to the national parks surveyed, while fewer than 2 percent were African Americans. The 2018 Outdoor Industry Association Participation Report put ethnic outdoor participation percentages for whites, Hispanics, Blacks and Asian Americans at 74 percent, 10 percent, 9 percent and 6 percent respectively.

One study by the University of British Columbia found that while income and education are strong factors, “racial and ethnic factors show stronger negative associations with urban vegetation in larger cities.” In other words, white residents had more positive associations with green spaces than Latinx and African American residents did.

So how do we avoid harming communities of color by sending them yet another message to stay away from the outdoors? We can first assess and acknowledge the impact our messaging might have on some of these populations.

As Nina Roberts, professor at San Francisco State University, and Caryl Hart, commissioner at the California Coastal Commission, wrote in their article “To Close or Not To Close,” which appeared in Bay Nature at the end of March, these closures compound an existing problem. “Generally, by preventing people from obtaining (park) benefits and more, even amidst a pandemic, we create additional problems not solutions,” they wrote. “Furthermore, other research also shows how low income and other under-resourced communities incur greater stress due to lack of access to parks in times of need.” This makes it clear that in addition to having to cope with a global pandemic, these communities disproportionately face physical and mental health problems that are amplified when the parks are closed.

As we move forward, it is important to take into account the human need to connect with the benefits of nature and the outdoors—especially when it comes to the most seriously impacted populations—while protecting the public health of everyone.

Parks and agencies, for example, can use this time to better ensure public health for disproportionally impacted populations by working with community-based leadership through groups and coalitions. The Parks Now Coalition in California and the Next 100 Coalition in Colorado, for example, are already invested in making the outdoors a more equitable place. Both groups were formed to increase park and outdoor access for underrepresented communities.

In the West, we have other good models to follow when it comes to ensuring equitable access to the outdoors during COVID-19: Cities like Denver, Colorado, for example are blocking off streets to cars to provide more recreational space for urban residents. Such efforts have similar effects to “pop-up parks,” the temporary reuse of space to provide park benefits. Other cities, including Oakland, California, have recently followed suit; Oakland opened up 74 miles of streets to walkers, joggers and cyclists.

The outdoor recreation and conservation community could do its part by shaping its messaging around going outdoors ethically with an eye toward equity. Helpful messages might include:

-

Reflect on what it means to have restricted outdoor access now that you are experiencing it, and consider that this has long been the norm for others.

-

Donate, if possible, to a community-based organization that supports outdoor access—much as you would to a food bank.

-

Speak up as an anti-racist ally when you are in public spaces, especially given the current rise in anti-Asian hate crimes.

Without such actions and considerations, I’m concerned that our decision to limit and close off park and outdoor access will take a disproportionate toll on the communities that need it the most, even as we debate the issue in our privileged spaces.