Mother Jones

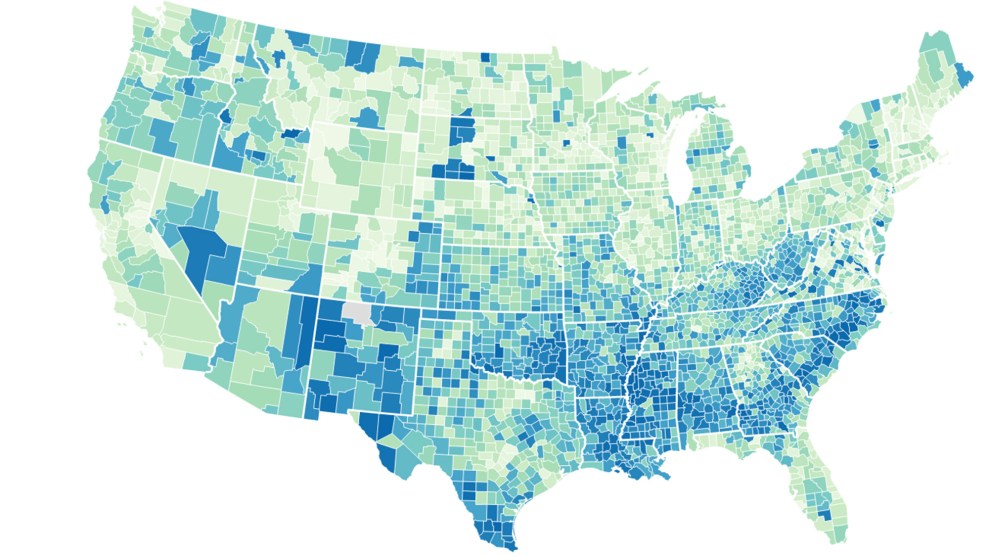

On April 8, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States hit a new high with more than 395,000 people reported to be sick. Yet many communities have yet to feel the full impact of the coronavirus. That impact could be especially heavy in vulnerable counties concentrated in the South, according to new research from the Surgo Foundation, a British nonprofit that uses data science to address global development and health care issues.

Data scientists at the foundation have developed a new metric called the COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index that is designed to capture where the impact of the virus will be most severe. It looks at 34 socioeconomic and epidemological factors such as residents’ poverty and income, age, race, and ethnicity, as well as their disabilities and underlying health issues and transportation, housing, and health care system capacity in their county. The index builds upon the Center for Disease Control’s social vulnerability index, which quantifies a community’s ability to cope with disasters in general.

Which counties are the most vulnerable when COVID-19 hits?

This index isn’t meant to predict which communities or individuals are most likely to be infected by the coronavirus. It is designed to capture where the impact of the virus will be the most severe given how quickly the virus is spreading across the country.

Most COVID-vulnerable states

1. Mississippi (90% of Mississippi’s counties are highly vulnerable)

2. Louisiana

3. Arkansas

4. Oklahoma

5. Alabama

6. West Virginia

7. New Mexico

8. North Carolina

9. South Carolina

“We thought it’s really important to look at COVID from the lens of vulnerability. And so this is not saying who is likely to get infected,” said Sema Sgaier, the executive director of the Surgo Foundation and an adjunct professor at Harvard University’s school of public health. Rather, the index is meant to answer the question, “Is that community able to cope in an adequate manner once COVID enters that community?” she says. “And if not, why? How can how can we upfront plan and allocate resources in a way that’s really going to allow that to happen?”

Data scientists at the foundation suggest that lawmakers and the media should pay closer attention to smaller, rural communities in the South that are highly vulnerable to the coronavirus but don’t have the resources to respond to the pandemic. For example, South Carolina’s Sumter County, which has a vulnerability score of 0.89 (on a scale of 0 to 1 with 1 being the most vulnerable), had 90 cases as of April 6, or around 83 cases per 100,000 people. Compare that with Santa Clara County (vulnerability score: 0.07) in California’s Silicon Valley, which experienced one of the earliest outbreaks in the country and currently has an infection rate of 63 cases per 100,000 people. The number of cases in Sumter is doubling every three days. Nearly half of its population is Black, 13 percent is uninsured (versus around 7 percent nationally) and nearly 19 percent are in poverty (versus the national average of around 12 percent).

According to Surgo’s analysis, regions such as New York, California, and Washington that have been hotbeds of the pandemic are not the most vulnerable areas. The vulnerable regions are beginning to catch up and more and more are seeing an outbreak now. It has also found that the virus is spreading 11 percent faster in vulnerable communities than in less vulnerable ones. As we have reported, some states, particularly in the South, have been slow to adopt public health policies that might have slowed the outbreak. And Mother Jones‘ Becca Andrews has explained how structural and socio-economic inequality have made it harder to practice social distancing in the South.

The foundation hopes that the index will help lawmakers anticipate the kinds of resources their states and counties will need as the coronavirus continues to spread. “We’ve been hearing stories, obviously, of New York and California and San Francisco and Seattle and Washington,” Sgaier said. “Those are not the highly vulnerable communities. It’s just now that the most vulnerable communities are actually experiencing COVID..and that requires a whole different set of attention, speed, and resource allocation.”