Marci Stenberg/Zuma

“Mass incarceration is a policy that makes no sense,” says Lauren-Brooke Eisen, the director of the justice program at the Brennan Center, a public policy institute. “This moment proves we don’t need to have jails and prisons bursting at the seams.” As the novel coronavirus has swept across the globe, infecting approximately 336,000 people in the United States and killing more than 9,600 as of Sunday night, epidemiologists and public health experts have warned that prisons and jails are the perfect incubators for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Packed in tight and often unsanitary living conditions, incarcerated people routinely have no access to soap and water and are frequently at higher risk for contracting illnesses because of underlying health conditions. These realities are at odds with the advice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and public health advocates that self-isolation and frequent hand-washing are the two best strategies for containing the spread of the disease.

The virus has illustrated just how vulnerable many people in the United States are, including low-income workers, unhoused people, and those behind bars. In response to fears of further contagion, many harsh criminal justice policies that were once seen as essential strategies for keeping the public safe are being abandoned as the virus spreads in prisons and jails across the country, where more than 2 million people are housed. All it took was a global pandemic.

“We’re seeing really important changes that we hope district attorneys and correctional departments will continue to push for once this pandemic is over,” Eisen explains. Across the country, people who have been arrested for low-level crimes, those who are getting close to their parole dates, suffering from certain illnesses, or otherwise pose no threat to public safety are being released back into the community in order to stay safe from COVID-19.

In Cuyahoga County, Ohio, for instance, judges began working to release people in jail last month. “It’s not a matter of if this virus hits us, it’s a matter of when,” administrative judge Brendan Sheehan told a CBS-affiliated news outlet in Cleveland last month. “If it hits us and the jail, it will cripple our criminal justice system.” The jail houses 1,900 inmates, a number he’s hoping to reduce by a few hundred by holding hearings to determine who is eligible to be released.

Similar measures are being taken in St. Louis, Missouri, where officials have sought to release more than 100 inmates from the St. Louis County jail, which was holding around 840 people. In neighboring St. Charles County, the jail population has been reduced by 14 percent. California is planning on releasing up to 3,500 inmates from state prisons over the next several weeks. Those inmates are those with nonviolent convictions who were set to be paroled within the next 60 days. While it’s a fraction of the 131,000 people incarcerated in the state, advocates say it’s a step in the right direction.

Some prosecutors are going further by not arresting people for committing the types of crimes that typically land individuals in jail in the first place. Baltimore prosecutor Marilyn Mosby ordered her staff to immediately dismiss pending charges for drug possession, prostitution, trespassing, urinating in public, and other low-level crimes. “An outbreak in prison or jails could potentially be catastrophic,” Mosby said. “Now is not the time for a piecemeal approach where we go into court and argue one by one for the release of at-risk individuals.” In Philadelphia, District Attorney Larry Krasner advocated for police officers to reduce in arrests for low-level arrests, and his counterparts in San Francisco urged the same. Time will tell if police officers heeded the advice.

Individual correctional departments are also becoming more flexible in their operations. Many prison and jail inmates have long been subjected to fees for basic needs like phone calls to their loved ones, soap, and medical care. Given the urgency of maintaining medical care, contact with family, and hygiene, some facilities are waiving fees. Ideally, Eisen says, she would like to see every facility waive fees for medical care.

Even the nation’s death penalty system has been impacted by the novel coronavirus. Death row inmates have seen their executions halted as neither the state nor defense teams can gather in large groups to carry out lethal injections. Texas has issued stays for inmates set to be executed between March and June. Indeed, one of the long-term consequences of the pandemic may be hastening the end of capital punishment nationwide. “I think there will be very strong arguments that this punishment is a kind of ‘legal luxury’ that we really cannot and ought not invest resources in while we try to rebuild after COVID-19,” Douglas Berman, a law professor at Ohio State University wrote in a blog post.

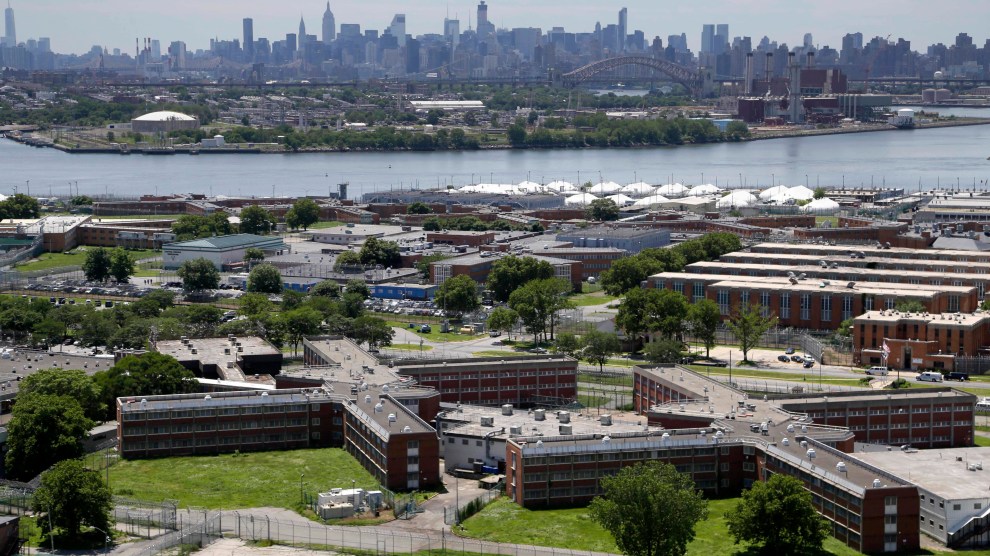

Of course, as with the state-by-state approach to battling the coronavirus, responses in the criminal justice system have varied, even from locality to locality. Criminal justice advocates have been advocating for releasing inmates at Rikers Island, New York’s jail where thousands are held before their trials and for short sentences. The jail facility, which is scheduled to close by 2026, is notorious for its dangerous conditions. As my colleague Samantha Michaels reported last week, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that 300 inmates would be released—but the jail complex currently has 5,000 people:

Public health experts say more drastic measures must be taken to keep the outbreak from growing. Public defenders are now petitioning the courts to free their clients who are still behind bars—many of whom are elderly and with preexisting health conditions. “New York cannot leave people in jails behind to suffer and die,” attorneys at the Legal Aid Society of New York City wrote in a lawsuit.

The federal government, unsurprisingly, is not following the advice of public health experts in their treatment of federal prisoners. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) recently proposed legislation that would have released at least tens of thousands of low-risk and elderly inmates in federal prisons and jails. Instead, the US Bureau of Prisons announced that federal facilities would be going on full lockdown, which could have the effect of further jeopardizing the health of prisoners, guards, and other prison workers. The virus is spreading in federal facilities and at least four inmates have died at a federal prison in Louisiana.

Some police officers and others opposed to wide-scale releases have claimed that crime will go up. It may be too early to tell, as John MacDonald, a criminologist at the University of Pennsylvania told the Marshall Project, “So many people are sheltering in place, crimes of opportunities are dropping. There are fewer potential victims out there.”

Eisen doesn’t yet see any reason to believe that a coronavirus crime wave is coming. “I don’t know what the future holds,” she says, “but this moment is illustrative that we don’t need to have so many people behind bars to create safe and thriving communities.”