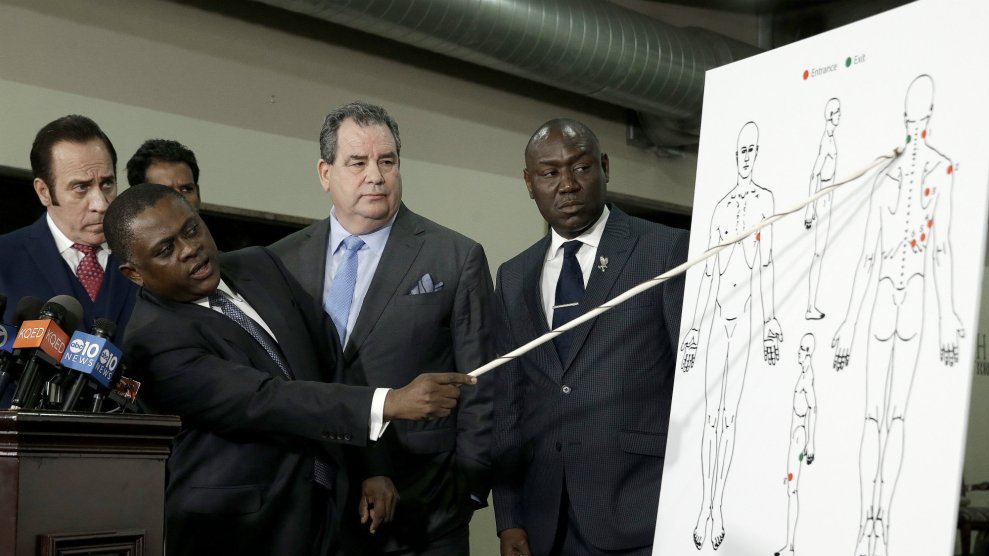

Bennet Omalu unveils the results of his autopsy of the body of Stephon Clark on March 30.Rich Pedroncelli/AP

On Tuesday, the Sacramento Police Department released the county coroner’s office’s report on the autopsy of Stephon Clark, the 22-year-old unarmed black man shot and killed in his grandparents’ backyard in March by local police officers. The results, however, are in conflict with the findings of a private autopsy commissioned by Clark’s family. The big question is why.

The private autopsy conducted on the family’s behalf found that Clark was hit predominately from behind after a bullet that struck him in the left side spun him around and exposed his back to further gunfire from police. Clark, who was standing on a patio attached to the house when he was shot, was facing the house with his left side exposed to officers when he was first hit. Bennet Omalu, the forensic pathologist who conducted the autopsy, said at a March press conference: “The proposition that has been presented that he was assailing the officers, meaning he was facing the officers, is inconsistent with the prevailing forensic evidence.”

An outside pathologist the coroner’s office enlisted to review its own medical findings, however, determined that Clark was first struck in his left thigh while walking toward officers and that he was hit predominately from his right side—not from behind, as Omalu argued. Omalu said in March he believes the bullet that pierced Clark’s thigh was the last bullet to strike him. The coroner’s office also found that Clark was hit by seven bullets, not eight, and that he had traces of marijuana, cocaine, and codeine in his system.

I spoke with Judy Melinek, a forensic pathologist who has conducted more than 2,500 autopsies and testified in more than 150 legal cases, about how two examinations of the same body might produce such different conclusions.

One key reason, Melinek says, is that the initial autopsy can result in changes to the body that make it more difficult for a second examiner to interpret whether a given wound is an entry or exit wound—or whether a wound was created by a bullet at all—without access to photographs, X-rays, and other records of what the body looked like before the first autopsy.

“The first pathologist cuts into the wounds. They will remove any bullets, slice open the wound tracks, and could create new wounds that look like gunshot wounds, but they’re not,” says Melinek. That can lead to discrepancies between autopsies regarding how many bullets struck a subject and in what direction the gunshots traveled through the body.

The removal of clothing from the body during the first autopsy can also pose problems for a second medical examiner. “If you’re wearing tight pants, or a tight jacket, or a do-rag on your head, the exit will look just like an entrance because the skin can’t lacerate easily. I have seen physicians make mistakes because they didn’t know the person was wearing a tight belt.”

Another pathologist, Howard Robin, further notes that the organs are detached from the body for closer examination during an initial autopsy, and are then placed in a bag and set back inside. That can create a major hurdle for a second pathologist who is looking to trace a bullet’s path through the body, Robin says, and can result in misinterpretations of the direction the bullet came from. “The most important thing when doing gunshot wound autopsies is: one bullet hole at a time, identify it as an entrance wound and then follow the trajectory of that bullet through that body,” he says. “The first person who does the autopsy certainly has an advantage over the second person.”

As for which bullet struck Clark first, Melinek says that’s hard to know without additional information, such as police body camera footage and witness statements that can help determine the positions of the people involved. So two experts with access to different information could reasonably come to different conclusions on that front.

In police shooting cases, the victims’ families often commission outside experts to conduct a private autopsy, separate from the official one. Howard says he recommends having outside pathologists participate in the autopsy alongside the county coroner, rather than doing a second autopsy later. However Melinek, who has done private autopsies in the past, says that’s not always allowed by the coroner’s office. Her policy was to wait until she had access to the records from the original autopsy before producing her own report.

Attorneys for Clark’s family released the results of the family’s autopsy first, but that autopsy was actually conducted a full week after the coroner’s office completed its examination. Omalu said he used police helicopter video of Clark’s encounter with law enforcement to determine which bullet struck him first. (Body camera footage was also available at the time.) But it’s unclear whether Omalu had access to witness statements or information from the coroner’s autopsy.

Gregory Reiber, the outside pathologist who reviewed the coroner’s findings, said he believes Omalu erred in interpreting what he determined was an exit wound in the chest—from a bullet he believes pierced Clark from the back—as an entry wound. This, Reiber argued, led “to incorrect conclusions regarding the relative positions of the victim and the shooter.” He did not speculate about other discrepancies between the two autopsies. Melinek and Robin both declined to say which report might be more accurate. Omalu, who is known for his discovery of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, defended his conclusions in an interview with the Sacramento Bee.