Midday on a May weekend in Minneapolis, Robin Wonsley Worlobah, a 29-year-old Black organizer running for City Council, stood outside a bungalow on the southeast side of the city. When a 75-year-old white man came to the door, she asked him to talk with her about the political issues weighing on him ahead of the election.

“For me, it’s the fight against the police,” said the man, whose face mask bore the logo of the US Navy. His brother had been a cop before retiring, as had some of his high school buddies. “It scares me to see the police department weakened,” he added.

Wonsley Worlobah, a Democratic socialist who joined the George Floyd protests last summer, has been organizing to shift funding away from the police. But she nodded empathically and responded, “I think it’s top of mind for everyone.”

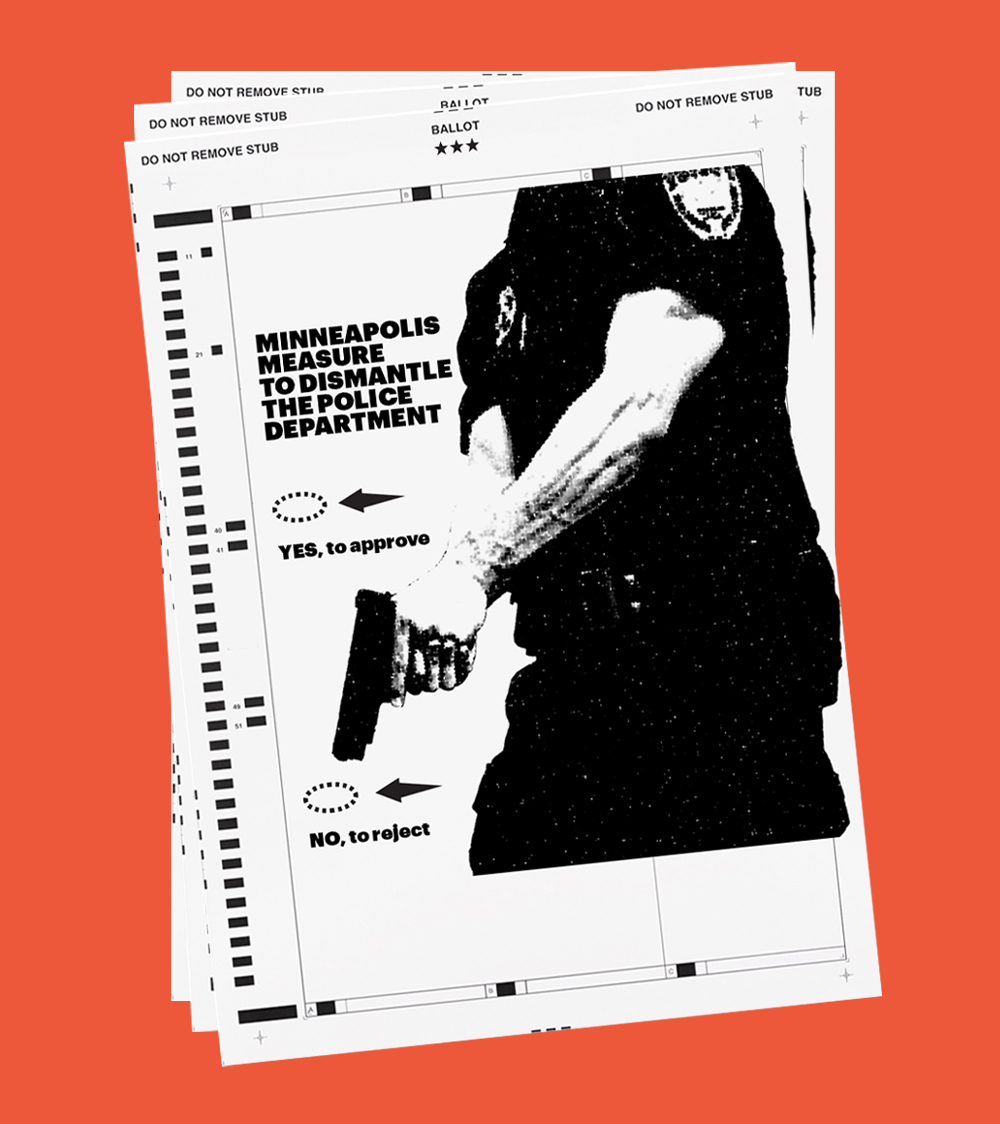

In the year since a cop murdered Floyd, with the city’s police department facing yet more allegations of racism and brutality, Minneapolis has become an epicenter in a national movement to reimagine what public safety looks like. This November, residents will have an opportunity to vote on a charter amendment that would let them dismantle the current police department and replace it with a Department of Public Safety, a proposal pushed by several City Council members and a Black-led coalition of activists. The new agency would likely still include armed law enforcement—though a smaller number of officers than before—along with unarmed social workers, violence interrupters, traffic safety responders, and homeless outreach coordinators who would proactively try to prevent crimes by helping people access housing, jobs, education, and health care.

Organizers talk with voters in Minneapolis about the charter amendment.

Barbershops and Black Congregation Cooperative

Robin Wonsley Worlobah, left, takes a break from door-knocking.

Courtesy of Robin Wonsley Worlobah

Black-led organizers have collected more than 20,000 signatures in support of the change—a big deal in a city where, according to council members, petition-driven charter amendments are rare. But to win, they’ll need more than half the total vote in November, which will be no easy feat: The amendment’s opponents include Mayor Jacob Frey and a group of pro-police activists calling themselves Operation Safety Now. They argue that shifting money away from cops will exacerbate the gun violence that surged last year during the pandemic.

Similar debates are happening around the country. From Oakland to Chicago to New York, Black organizers have called on cities to downsize or abolish policing for decades, and the moment after Floyd’s death presented an opportunity to take their message to a broader audience.

But they’ve got their work cut out for them as they confront an image problem that their critics have been keen to latch onto: Even though up to 26 million people protested police brutality last summer, some topline poll results seem to suggest that many Americans reject the defund movement. One survey in March, by market research firm Ipsos and USA Today, found that only 18 percent of respondents supported it.

Centrist Democratic politicians and pundits have pointed to these polls as proof that the defund movement will never gain enough popularity to be worth trying. Journalists, too, often recycle this sentiment, citing survey data to suggest that defund organizers are reaching for a near-impossibility. “I don’t know any communities, particularly the communities that are in most need and the poorest and the most at risk, that don’t want police,” President Joe Biden, who supports using federal funding to hire more law enforcement, said in a town hall in July.

Former President Barack Obama has likewise argued that activists should not embrace a “snappy slogan” that could alienate moderate voters. “You’ve lost a big audience the minute you say it, which makes it a lot less likely that you’re actually going to get the changes you want done,” he said in December during an interview on the Snapchat political show Good Luck America. “‘Defund the police’ is killing our party,” Democratic House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn said in November after the election, arguing that Republicans would use the movement as a weapon against liberals.

The way defund organizers and their allies see it, these demurrals offer up defeatism in the guise of pragmatism, as if the impulse that brought Americans out into the streets in record numbers could not also dislodge long-standing premises about crime and policing. So Minneapolis activists like Wonsley Worlobah are going door to door ahead of the election to push back against that defeatism, pressing the case for why their own platform makes sense and why traditional law enforcement will not stop the shootings. As the campaign for the charter amendment heats up, the porches and front yards of the Twin Cities have become a testing ground for the politics of the defund movement. Can organizers sway those supposedly implacable Americans from the prevailing “law and order” consensus? Can they seize this moment when people of various backgrounds are questioning whether cops really keep communities safe?

“The thing is, I want to back the police,” the man with the US Navy face mask told Wonsley Worlobah with a sincere look in his eyes. “But I don’t want to back people like this idiot that’s on trial,” he added, referring to Derek Chauvin, the police officer who killed Floyd and was recently sentenced to prison. “That’s flat-out murder—there ain’t no doubt about it.”

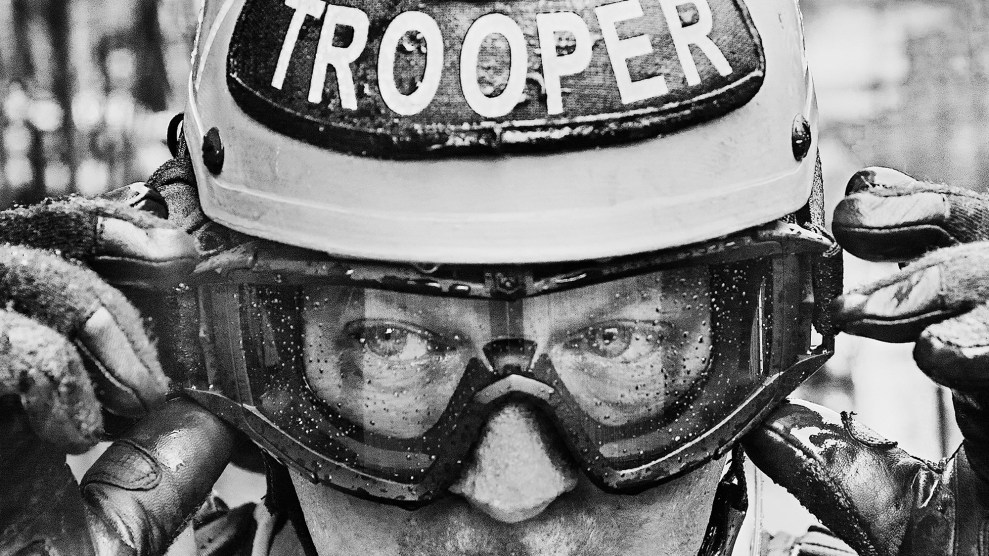

Wonsley Worlobah nodded in agreement. “Yeah,” she said, considering her next response. “Not every crisis needs someone coming up with a gun,” she added later, easing into her pitch. She offered the man a different way of thinking about safety, one in which the real threats to public order are the hypermilitarized cops and the lack of social provision. Yes, she allowed, the city might require “an armed force that can respond to more violent crimes, but we still need to be taking away military-grade weapons.” She recalled last year’s crackdown on protests near the police department’s Third Precinct. “It was children out there, like families, and you’re using irritants like tear gas. As someone who has asthma—unnecessary,” she said. “So I think taking away military-grade weapons—like, you should not have tanks in our community.”

Having established the police as occasional perpetrators of violence against the public, Wonsley Worlobah now sought to enlarge the man’s definition of safety: “We talk about rent control. We’re talking about taxing the rich to fully fund our schools—that’s part of public safety. Having public safety is making sure your neighbors can stay in their communities and not end up in homeless shelters, in our parks.”

By talking more deeply with voters in this way, Minneapolis organizers are betting they can gain allies. Because while only 18 percent of respondents in the Ipsos/USA Today survey claimed to support the defund movement when asked directly about the term, a much higher number (43 percent) said they supported redirecting police funds to social services in the community—which is exactly what the defund movement calls for. “That nuance is missed” in the media and by politicians “because of the focus on who likes the phrase ‘defund police,'” says Amara Enyia, a Chicago-based activist with the Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of grassroots groups around the country. Another poll, by Data for Progress, found that 55 percents of respondents nationally supported proposals to route certain 911 calls related to homelessness, mental health, minor crime, and substance abuse to unarmed civil officers, social workers, counselors, and EMTs, as long as police would still respond to serious felonies and significant acts of violence.

“It doesn’t make sense to ask people if they favor ‘abolishing’ [or defunding] the police, because nobody knows what it means,” adds Alex Vitale, an organizer and a sociology professor at Brooklyn College who wrote The End of Policing. He believes pollsters focus on the much-demagogued term with “the intent of discrediting” the movement. “Nobody who’s organizing in communities is going out door to door saying, ‘Will you sign a petition to abolish the police?’ What we’re asking people is, should we hire counselors instead of school police? Should we have public health strategies to deal with drug problems? It turns out that when we ask people those questions, there’s broad public support for it.”

Some other movement leaders agree. “If you try to make a set of words toxic and then ask people about it, you’re going to get a predictable result,” Andrea Ritchie, a police misconduct attorney and an organizer in New York, says of the polling. “But if you ask people about what the actual demands are, many more people are supportive of them, because that’s where the demands came from: They came from communities who wanted something more and different and better than what was being offered.”

In Minnesota, activists are showing that by reframing the issue and engaging with a broad group of people, including those who might be put off by the phrase “defund the police,” they can achieve progress. “What they’re doing is laying a groundwork that other municipalities can look to,” says Enyia. “They’ve done an incredible job mobilizing,” says Ritchie.”The more they talk to people, the more they win people over,” adds Vitale.

“All eyes are on Minneapolis,” Corenia Smith of Yes 4 Minneapolis, the Black-led coalition that’s heading up the petition to restructure law enforcement in the city, tells me. “We are creating a blueprint for folks across the nation.”

Police abolitionists have been working in Minneapolis for years, but their current push to establish a Department of Public Safety began in February on a freezing Saturday near the Third Precinct, which protesters had set on fire months earlier after Floyd’s death. Activist Julia Johnson, 29, trying to spread the word about the petition to dismantle the police department, posted a flyer on a pole that still appeared charred from the flames. She recalled how cops had shot tear gas and rubber bullets near her during those summer demonstrations.

But on this February day, the scene outside the Third Precinct was totally different: Temperatures had dropped below zero, and canvassers under tents huddled in their winter coats with clipboards to collect people’s signatures. Johnson, passing out hot chocolate to other organizers, felt invigorated by the number of people who came by in the cold to learn about the proposed Department of Public Safety. “It was a huge, huge swell of support,” she says.

For organizers in Minneapolis, proving the community is on their side has been critical. For weeks after Floyd’s death, it appeared as if local officials might find a way on their own to reduce the number of armed cops patrolling the streets—particularly after a veto-proof majority of the City Council, facing pressure from activists, pledged in June 2020 to “end policing as we know it.” But council members soon ran into a legal roadblock: The current Minneapolis charter, a sort of constitution for the city, requires the government to staff more than 700 police officers, a calculation based on the city’s total population. Last fall, when council members tried to change the charter in a way that would remove this requirement, an unelected charter commission thwarted their plan. So Black-led activist groups stepped in and decided to take matters into their own hands.

Since February, hundreds of volunteers have gone door to door, held events, and organized COVID-safe drive-throughs to share information about their proposed charter amendment. In addition to creating a Department of Public Safety, the amendment would remove the minimum staffing requirement of armed officers. The Yes 4 Minneapolis coalition, which includes grassroots racial justice groups like Black Visions and Reclaim the Block, got support for their canvassing work with a $500,000 donation from the DC-based Open Society Policy Center, the lobbying arm of the Open Society Foundations founded by billionaire George Soros. At the end of April, they submitted more than 20,000 signatures to the city, enough to qualify their proposal for the ballot. In total, Black Visions and Reclaim the Block say they’ve raised more than $30 million in donations since Floyd’s death.

“It’s fairly remarkable when you think about the sustained energy it’s taken for this community to push for structural change against some substantial democracy roadblocks that we ran into,” says Steve Fletcher, a council member who supports the amendment to create the new department. “Particularly during the pandemic, for people to find a way to get 20,000 physical signatures on this petition shows tremendous, tremendous momentum.”

One goal for activists is to reduce the number of armed officers in the city so that it’s more proportional to the percentage of 911 calls that actually might require an armed response. A study last year of 10 cities around the country (not including Minneapolis) found that only about 1 percent of calls for police service were related to serious violent crimes. Organizers haven’t proposed a specific number of armed officers for Minneapolis yet; they’d do that after the amendment passes, in consultation with community members, while working with council members and the mayor to flesh out specifics for how the new department would operate.

Some of the organizers are driven to shrink the police’s presence in their communities due to their own past experiences of abuse by law enforcement. About four decades ago, activist Julia Johnson’s grandma was chased out of her home in Everson, Pennsylvania, by the Ku Klux Klan, which counted the sheriff among its members. “My initial mistrust of police is from knowing what happened to my family,” Johnson says.

Wonsley Worlobah, the city council candidate, grew up on the South Side of Chicago, where the police raided her childhood home and sent some of her loved ones to prison for drug possession. “I’ve been in schools that have been heavily defunded; I’ve been in subpar housing,” she says. “I’ve experienced the effect of not pouring resources into our communities but then instead relying on policing to deal with the effects of poverty. And having my family be traumatized by it.”

“The police do not prevent crimes,” says Kennedy-Ezra Kastle, an activist with Black Visions. But especially as community shootings surge, the challenge ahead is convincing people from different backgrounds who might not agree. “There’s been tons of fear that any type of change to policing is going to lead to extremist results, like there’s going to be lawlessness across our city or criminals are going to terrorize you,” says Wonsley Worlobah. “The opposition is doing a really good job around advancing a pro-cop campaign in our city.”

Williams during a canvassing event

Nance Musinguzi

Certain crimes are rising, in Minneapolis and around the country. The question now is whether this surge in violence will derail the movement to defund police, or fuel it.

At the intersection in south Minneapolis where George Floyd was killed, a memorial space filled with flowers and candles has become a place for people to gather, pray, and talk with their neighbors. But the blocks surrounding George Floyd Square have also seen an increase in gunfire so extreme that some food delivery drivers reportedly began avoiding the area last year. In certain cases, residents have dragged bloody victims for blocks because barricades that surrounded the memorial until recently kept ambulances from entering.

The rise in shootings has happened nationally, in big cities and small towns led by Democrats and Republicans alike, even while other types of crime have dropped. Across the country, killings increased about 25 percent in 2020, resulting in thousands of additional fatalities—though Americans are still much less likely to be shot dead today than they were in the 1990s. Minneapolis saw homicides jump from 48 in 2019 to 84 in 2020, a percentage leap greater than the national average. And killings have continued to rise there in 2021, mirroring trends elsewhere. Much of the bloodshed has occurred in under-resourced neighborhoods of color.

“It is a major challenge,” says Fletcher, the council member, about the rise in shootings. “Anytime you try to change the system of policing, the first time anything goes wrong, the first time there’s a crime, there are people who point to that and say, ‘You see, we need police.’”

Criminologists believe the violence is connected to the economic devastation and social isolation spurred by the pandemic, which also coincided with record gun sales. But as my colleague Nathalie Baptiste has reported, conservative politicians, media figures, public officials, and others have attempted to blame the violence on the defund-police movement, even in cities where activists failed to divert substantial funds from cops.

In Minneapolis, a group of residents on the north side calling themselves the Minneapolis 8 sued the city last October over police staffing levels, arguing there weren’t enough officers to keep people safe. In July, a judge ruled in their favor and ordered the city to hire more cops in order to comply with the charter. (The situation has been complicated by the fact that about 200 Minneapolis officers quit, retired, or took time off after the protests last year; in November, the City Council approved hundreds of thousands of dollars to fill these staffing gaps, before diverting $8 million overall from the police department’s roughly $179 million budget. In February the council approved $6.4 million more to hire new cops.)

“When you make big, overarching statements that we’re going to defund or abolish and dismantle the police department and get rid of all the officers, there’s an impact to that,” Mayor Jacob Frey, who opposes the charter amendment, said during a meeting with community leaders in May. This was a week before a 6-year-old girl was shot in the head while riding home in the car with her mom, raising more concerns about crime. Frey has argued that the city must invest in cops. “Do we need massive change? Yes, we do. We need accountability and culture shift within our department, and we need police.”

In an interview with Mother Jones, Frey adds that he’s not against creating a Department of Safety per se, including one that gives more resources to mental health responders and social workers. But he doesn’t want to reduce the number of police officers in the city. “Having a comprehensive approach to public safety that’s based on public health—I’m for it,” he says. “Where I part ways, and where quite a bit of community part ways as well, is this notion of getting rid of more officers when we already have one of the lowest number of officers per capita of any major city in the country.”

Other pro-police groups have allied with the mayor and the police chief, including a new coalition called Operation Safety Now. Its leader, Bill Rodriguez, who runs a marketing company, put out a call in September on the social media platform Nextdoor inviting crime victims to speak about their experiences. Rodriguez lives in Richfield, a Minneapolis suburb, but initially identified himself as a Minneapolis resident because he thought it was the only way for him to share his opinion at a meeting with council members, according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune. (Rodriguez declined an interview request from Mother Jones.) He told local reporters that his wife’s south Minneapolis home had been burglarized, and that they both hid in a closet clutching a baseball bat while waiting for the police to arrive. According to the Minnesota Reformer, a police officer who responded to Rodriguez’s call saw no evidence of a burglary and said it was just a false alarm.

Meanwhile, the pro-police group All of Mpls, led by Steve Cramer of the Minneapolis Downtown Council, has raised more than $100,000 to campaign against the charter amendment with door-knocking, community events, mailers, and digital ads.

It’s unclear how many supporters these groups count among their ranks. Operation Safety Now has about 1,300 followers on Facebook. That pales in comparison with Reclaim the Block, one of the organizations pushing to defund police, which has about 25,000 followers on the social media site.

But Operation Safety Now has “an outsized voice” in the debate, according to the Reformer, partly because of connections its leaders have formed with Mayor Frey, Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, and other city officials. Last November and December, as the City Council prepared to vote on the police department’s budget, Operation Safety Now’s Rodriguez communicated with aides to both the mayor and the police chief as he campaigned against defunding, according to emails obtained by the Reformer via public records request. Arradondo gave an interview for an OSN video, and the mayor’s office emailed with Rodriguez, offering input on a form letter he’d crafted to encourage people in the city to support the mayor’s proposed budget for the police department.

Operation Safety Now has other powerful allies: Its umbrella organization, according to the Reformer, is the group MPLS Voices, whose members reportedly include Charter Commissioner Jana Metge, who serves on the commission that recommends which charter amendments reach the ballot. Operation Safety Now is also linked to MPLS Together, a pro-police group whose supporters include at least a couple of former city council presidents, along with former NFL defensive back Tim Baylor and former Minneapolis Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton. OSN leader Eric Won was re-appointed by Frey last year to a city committee that makes proposals about how Minneapolis spends tax dollars.

Frey has a clear interest in helping Operation Safety Now and opposing the activists pushing for a charter amendment: If the amendment passes he would no longer have complete control over the police department’s operations and policies. Under a Department of Public Safety, he’d share power in these matters. And the City Council would assume legislative control over the department, making law enforcement more accountable to the public and less accountable to him. “I don’t support shifting the reporting structure so that the head of public safety would have 14 bosses—13 council members and a mayor,” Frey tells me. “When everybody is in charge, nobody is in charge.” He adds that his office had emailed once with Operation Safety Now but says his team also met with Reclaim the Block activists. “When people reach out, we meet with them and we’re transparent about what our position is,” he says.

Some activists blame Frey, who is up for reelection, for what they describe as a slow pace of change in Minneapolis since Floyd’s death. Nearby Brooklyn Center, a suburb led by a Black mayor, approved sweeping reforms just one month after an officer killed Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in April; those reforms will include a new agency to oversee public safety, merging the police and fire departments alongside departments for traffic enforcement and community response.

“Let’s connect the dots,” says Black Visions’ Kastle, who works in Minneapolis. “Their mayor is a Black man. Our mayor is a white man who benefits from the system of white supremacy.” The reforms championed by Frey have included piecemeal changes like policies requiring police to intervene when a fellow officer uses unauthorized force, rather than the creation of an entirely new department. Other reforms include a ban on chokeholds and most no-knock warrants.

Frey defends his record, noting that Brooklyn Center still needs to implement its resolution. “Are any of these [reforms in Minneapolis] going to totally shift the culture of the police department? No,” he concedes. But “the things we’ve done are not plans in the future—we’ve done them.”

Though he says he wants to support “fundamental systemic change” in public safety, Frey has regularly pushed to bolster the resources of law enforcement, with some success: In late 2020 and earlier this year, after he and Operation Safety Now recommended more money for cops, City Council members set aside millions of dollars to fill police staffing gaps and pay overtime, and they voted against a measure to cap the number of officers at 750. And in July, the council approved his plan to give some of the city’s federal coronavirus relief funding to the police department.

Despite these challenges, Black activists believe they can persuade voters to approve a Department of Public Safety in November as long as they find the right messaging. “A lot of it is getting away from the propaganda that the mayor and pro-police unions have created together,” says Kastle. In particular, defund organizers see the rising violence in Minneapolis as a reason to join their cause, not oppose it: The police, they argue, are not helping the shooting victims who need assistance, especially around George Floyd Square.

Violent crime increased substantially last year in Powderhorn Park, Central, Bryant, and Bancroft, four neighborhoods surrounding the square, according to police data. But Julia Johnson, one of the activists from Black Visions, who lives nearby, says the cops often don’t show up when residents call 911 after robberies, car break-ins, and shootings. “The police have a vendetta against the community, and they’re retaliating for the activism,” she says.

Some organizers speculate that officers stayed away to knuckle the city into hiring more cops. “It is a very hard thing to prove,” says Fletcher, the council member. “I do think there are places where individual officers are deciding not to engage in a situation, or I’ve heard people describe it as a slowdown. I don’t think we know if it’s an intentional labor tactic.” (The police department did not respond to a request for comment.)

Council Member Jeremy Schroeder has also heard complaints about police avoiding places around the square, but he says officers have assured him they are trying to keep the area safe. “That difference in what we’re hearing is exactly why we are pursuing this change,” he says of the need for a Department of Public Safety. “We want to make sure everyone in all parts of the city is safe. At George Floyd Square, there are a lot of complex emotions. It will take a much more holistic approach.”

Offering alternatives to policing could appeal to residents who have lost trust in law enforcement and its ability to help them. Shortly after Johnson moved to Minneapolis about two years ago, she called the police because a loved one had gone missing during a mental health crisis. She soon grew disillusioned: She says the officer she spoke with on the phone laughed when she asked whether she should file a missing-persons report, saying there was nothing the police department could do. Whatever faith she had left in cops quickly disappeared.

Robin Wonsley Worlobah talks with a 75-year-old voter about public safety

Courtesy of William Tyner

That doesn’t mean these Black activists want to immediately get rid of all armed cops in Minneapolis. While talking with voters, organizers have heard again and again that people want access to mental health responders, homeless outreach, and other social workers but are not ready to completely abandon the police.

“Nobody we were talking to was prepared to not have any law enforcement at all,” says Brian Fullman, who leads the Barbershop and Black Congregation Cooperative, a coalition of barbers and beauty shop organizers who try to get more Black voters to the polls in Minnesota. His team has held events about the proposed charter amendment, and he’s helped go door to door. As he sees it, the Department of Public Safety would make room for everyone: “If you feel like you don’t want law enforcement, there’s a space for you. If you need law enforcement, there will be law enforcement. What I started realizing when we talked to people in the doors was that they were really with that,” he says.

Fletcher, the council member, says that while fewer armed officers would likely have jobs under the new agency, they would not disappear. “In many cases it’s actually been our opponents who’ve tried to suggest we’re suddenly abolishing the police force,” he says. “They’ve sort of put words in our mouths in a way that has caused confusion.”

In July, city officials added an “explanatory note” to the ballot measure about the Department of Public Safety, emphasizing that it would remove the police department and chief from the charter. Progressive organizers viewed the note as a dirty trick aimed at dissuading voters; they successfully sued to have it removed last week. The note was “easily misconstrued” and “inevitably biased,” they wrote to the court. Robin Wonsley Worlobah, the city council candidate, tries to clarify to voters that a Department of Public Safety would provide more options, not fewer: “They just want to know, with the proposals that are out here, how are you going to respond to my moments of need? And our role in our campaign is crystallizing that.”

In a poll last August, more than half of likely voters in Minneapolis said they liked the idea of creating a more comprehensive, holistic Department of Public Safety. And another poll showed that nearly three-quarters of the city’s registered voters supported cutting the police budget and spending more on social services. But only 35 percent of Black respondents and 41 percent of white respondents said they wanted to reduce the size of the police force.

With the stakes so high, some organizers are treading lightly when talking with voters. Corenia Smith, who leads the Yes 4 Minneapolis coalition, is careful about what words she uses to describe her goals. “We’re not ‘defunding’ or ‘abolishing’ the police,” she tells me. “We’re removing existing barriers to achieving a holistic approach of safety for everyone.”

Recasting the conversation can help persuade people, says Wonsley Worlobah. “Folks are like, ‘I mean, I do want someone to show up when I’m in crisis,'” she says. She tells them that under the new department, someone would still show up, and 311 and 911 would still exist. “The only difference is you will have a trained public safety worker in the area of crisis that you are dealing with”—a substance abuse counselor, for example—”as opposed to a person with a blue uniform and a gun and no experience in those types of crises,” she says. “When you break it down to folks in that way, they’re like, ‘Oh, okay! Okay, I get that.'” Then she asks people if the money currently going to the police department should be redirected to those new workers. “They’re like, ‘Oh, yeah!'” she says.

Organizers are persuading people, says Enyia of the Movement for Black Lives, not by telling them what to believe but by giving them information that helps them ask questions about problems in their own lives. If community members tell activists that their kids’ classrooms are in disrepair, or that they’re inhaling toxic factory fumes, or that their friend can’t find a therapist, activists will explain how much of the city’s budget goes toward police. “When you walk people through so they themselves can connect the dots, people will say, ‘Yeah, why do we spend so much money on policing versus economic investment in communities?’ People will start to ask those questions themselves,” says Enyia. “It takes work. It doesn’t fit neatly within a poll that says most people don’t support defunding.”

Sometimes activists in the coalition are more forthright. Johnson of Black Visions says certain voters get excited and understand where she’s coming from when she canvasses in her face mask that says “Defund Police” across the fabric. It’s all about connecting with people where they’re at. “I don’t have any issues with switching up the language, you know, depending on our audience,” she says. When she recently entered a grocery store the day after a police shooting on the south side, a Somali youth who worked there enthusiastically approached her after seeing her “defund” face mask. Yes, yes, we need to change, she recalls him saying. They just killed that brother yesterday, and you know, we’re sick of it.

“So when we say defund the police, it resonates with some folks in a way that they understand exactly what we mean, that this institution has completely failed us, and that it has succeeded in its goal of upholding white supremacy and oppressing Black and brown people,” she says. The Somali grocery store worker told her he wasn’t very engaged in politics or organizing. “But he saw that mask,” she says, “and he knew exactly what I was talking about. He was excited.”

Part of that excitement comes from imagining what might come next. While the anti-defund demagogues evoke the specter of absence and abandonment, organizers are trying to define their movement as an active, robust presence in the life of the city—a way to offer people more services, more help, more support. Winning allies, says Woods Ervin, an activist at the abolitionist group Critical Resistance in Oakland, “is less about reframing and more about providing clarity for the robustness of what defunding-police movements are trying to do.”

At the bungalow in southeast Minneapolis, Wonsley Worlobah continued talking with the 75-year-old man in the Navy face mask, who, despite his family’s connections to law enforcement, seemed eager to find common ground. He told her that days earlier, he’d been disappointed by the police’s slow response when he called them on a walk in the neighborhood. He’d noticed someone in the middle of a mental health crisis yelling at young kids on the sidewalk in a threatening way. “If that had been an emergency, it would have been over,” he told her.

Wonsley Worlobah nodded. “That’s the big thing, and why again we support mental health dispatchers,” she told him. “Because as you mention, police tend to show up after a crime has already been committed.” If the guy on the sidewalk had been arrested under the current system, she surmised, the police might have thrown him in jail for a couple of days, but he likely would have been released again without the care he needed to avoid a similar meltdown in the future.

“What if we have a different type of proactive response?” she said. “If you have a mental health dispatcher come through, it’s like, okay, we know what programs to plug you into so you’re not out on the streets in this particular condition and also making other people feel unsafe.”

“Yes, yes, yes,” the man outside the bungalow said. “No question about it.” He nodded along as she spoke. Despite some of their differences, maybe they were on the same page after all.