The men's intake center at the Los Angeles County jailACLU court filing

As a criminal justice reporter here at Mother Jones, I get emails and letters every week detailing the horrific conditions at correctional facilities. But when I read one about what’s been happening at the Los Angeles County jail, the biggest jail in the country, my jaw actually dropped open.

The jail is overseen by Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who is up for reelection in November, and is at the center of several scandals, including his resistance to ending his department’s “deputy gangs,” or cliques of officers with matching tattoos and names like the Executioners and Grim Reapers.

In recent years, the jail has seen an influx of men arrested with mental health problems—and it doesn’t have enough special beds to accommodate them. As a result, some of these men are being chained to chairs in the jail’s intake center for days or even a week at a time, waiting for a bed to open up, according to a new legal filing by the ACLU. Sometimes jail staffers aren’t letting them up to use the toilet, so they are forced to defecate and urinate on themselves and on the floor, in trash cans, or in the juice boxes they are given to drink. They are allegedly denied showers afterward—as well as access to their medications. Many sit with their shirts pulled over their heads, trying to block the fluorescent lights after days without proper sleep.

County officials did not deny this is happening, after ACLU attorneys complained in court. “Lamentably, Plaintiffs are largely correct that conditions inside the Inmate Reception Center of the Los Angeles County Jail have deteriorated dramatically in past months,” the county’s attorneys wrote in a court filing on Monday, admitting that men were handcuffed to chairs for long stretches of time, and not refuting allegations about poor access to toilets and showers. Men “have been held in that space for well beyond 24 hours while waiting to be assigned to housing designed to accommodate their needs.”

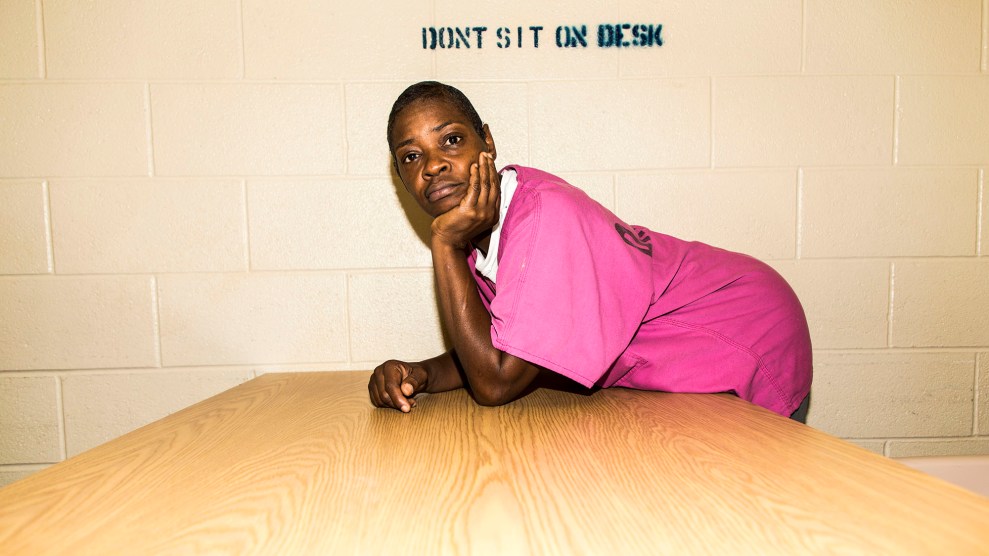

Men handcuffed to chairs in the intake center

ACLU legal filing

How did things get so bad? The LA County jail system isn’t just the biggest in the country; it’s the biggest in the world, incarcerating upward of 14,600 people this month. Its male intake center processes thousands of individuals each week, the vast majority of whom have not been convicted of a crime but are awaiting trial or other legal proceedings. And in recent years, the number of them with mental health problems has grown considerably because Los Angeles County, like others counties around the country, has failed to invest enough money in mental health care and community alternatives to incarceration. Last year, about 40 percent of the jail’s total population had a diagnosed mental illness, compared with about 27 percent back in 2012.

A few thousand of these detainees are sick enough with suicidal thoughts, mood problems, or psychotic symptoms that they must be placed in special housing units with extra observation from staff; the number who are eligible for the highest-observation units alone has grown from 460 in 2012 to 1,577 today, according to county data. They are supposed to be placed in these units after no more than 24 hours in the jail’s intake center, which does not have beds or other basic accommodations. But these special housing units are “in short supply,” the county’s attorneys wrote in the court filing, which means that people recently have been forced to wait much, much longer.

On a single day in August, a whopping 252 people had been stuck in the men’s intake center for longer than 24 hours; many had been there for several days, or even a week. Wait times increased over the summer, after the Los Angeles Superior Court ended a statewide, pandemic-era order about bail schedules that had decreased the number of people that could be jailed before they went to trial. While most of the men in the intake center are allowed to move around as they wait, some with serious mental health symptoms are handcuffed to chairs. On that same day in August, 22 people had been chained for more than three days—significantly longer than the limit of just two or four hours recommended in most jail policies nationwide, according to the ACLU filing.

When ACLU attorneys visited the intake center in June and August, they observed shocking conditions. Dozens of people tried to sleep while chained, and hundreds of others slept on floors and metal benches, often surrounded by trash. Nobody had mattresses or blankets. “I ache all over,” Curtis Howard, one of the detained men, told the attorneys in the center four days after he arrived there. “It is so uncomfortable I sleep only an hour or two at a time.”

He added that some of the handcuffed men “yell for the deputies to unchain them so they can go to the bathroom. But the deputies ignore them, so they urinate on the floor.” Even men who could walk around struggled to use the toilets, because they were overflowing, and instead urinated in sinks—making it hard for others to quench their thirst. “There is no water,” Ira Porter, another detainee, told the attorneys. “The sink is nasty and smells like urine and feces and stuff is floating in the water.”

One man said that while he was tethered to a chair, another handcuffed man next to him defecated on the floor, and it was not cleaned for two days. Multiple men told the ACLU they were not allowed access to showers or fresh clothes; one man was denied a shower even after defecating on himself. “The conditions I observed in the ‘clinic’ were appalling,” Peter Eliasberg, chief counsel at the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, said in a declaration to the court. He and his colleagues were informed that jail staffers hardly ever cleaned, except for prior to the ACLU visit. Even then, one attorney observed a man in a suicide gown lying on the floor in the middle of a puddle of urine.

Men in the intake center also allegedly struggled to get medical care, according to the ACLU filing. Some were abruptly forced to stop their psychotropic or chronic care medications, while others detoxed from drugs or alcohol with little oversight or assistance. One man who said he was an insulin-dependent diabetic told the ACLU he had not received insulin for 36 hours and had been fed only peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and orange juice, which made his blood sugar spike and crash. Another man with a peanut allergy said he did not receive any alternative to the peanut butter sandwiches for breakfast and lunch.

The attorneys saw a man in a wheelchair crying while holding up his hands, showing how they were curled up and swollen, and another man with a fist-sized hernia, hunched over in pain. “I am hearing voices and I feel like I am falling apart,” said Chuck Bethel, who was abruptly taken off his psych medication for bipolar schizophrenia. A psychiatrist in the center allegedly told him he could not get his medications until he received his housing placement. “I have been crying on and off since I have been here…I was thinking about suicide but don’t want to tell anyone because if I do they will chain me to a chair.”

In April, a man was discovered unconscious in the center and died even after receiving emergency aid. In June, another man died after two days in the center without a medical evaluation.

County officials told the court this week that they had recently taken steps to address these problems, including relocating other detainees who were already admitted to the jail, to open up more special housing units for newly arrested men with mental illnesses. These changes led to a decrease in wait times in the intake center over the past couple of weeks, the officials said. They added that newly arrested men are allowed to shower right before they enter the intake center, and that they undergo a medical screening at the center. “The purpose of tethering a person to the [chairs] is to ensure the person’s safety, and…to ensure that custody staff are able to continuously, directly observe all those who pose a high risk of self harm,” the attorneys wrote.

The county officials told the court that they would follow a proposed temporary restraining order prohibiting them from holding anyone in the center for more than 36 hours, with the goal of keeping people there for no more than 24. The order would also require officials to provide documentation to the ACLU anytime someone was handcuffed, chained, or tethered to chairs for longer than four hours.

A judge is expected to rule on the restraining order on Friday. But without drastic changes, it seems likely that people will continue to suffer in the intake center. “It is like a living hell in here,” Gilberto Perez, another detainee, told the ACLU attorneys. He did not have access to his asthma medication, so his breathing felt labored. He was exhausted and said he had slept just three or four hours over nearly as many days. “The deputies treat us like animals and don’t give two shits about us.”

The Sheriff’s Department clearly has a lot of work to do to improve the jail’s conditions. And yet as the midterms approach, its officials appear rather distracted by other matters: This week they accelerated investigations, even after prosecutors declined to press charges, into two of Sheriff Villanueva’s political enemies, including a county supervisor and a member of a civilian oversight commission who previously criticized him and called on him to resign.