Today, the Obama Administration begins its first trial of a prisoner held at Guantanamo Bay. The defendant is Omar Khadr, a Canadian national who was 15 when his alleged crime took place eight years ago. Since that time, Khadr has been abused, threatened, and held is solitary confinement for long periods at both Bagram and Gitmo. Daphne Eviatar of Human Rights First, who is at Gitmo covering the trial, deduces why the administration has chosen to have a former child soldier tried by a military commission, rather than in civilian court:

Perhaps the government hopes that Khadr’s statements, which he claims were extracted by various kinds of torture and abuse, will be allowed into court as evidence. Although Khadr’s lawyer hasn’t yet had the opportunity to present all the evidence of his client’s treatment at Bagram and at Guantanamo Bay, what’s come out at pretrial hearings so far is that when Khadr was captured by U.S. soldiers in July 2002, the teenager had been shot twice in the back, blinded in one eye and had a face peppered with shrapnel. Interrogators at the Bagram air base took to calling him “Buckshot Bob.” But that didn’t stop them from interrogating him while he was still recovering from life-threatening wounds and strapped to a hospital gurney. Using what the military calls a “fear up” technique, an interrogator testified, Khadr was told a story about another prison just like him who refused to cooperate – and who then was gang-raped and killed in an American prison.

Official documents also reveal that at Guantanamo, Khadr was subjected to the military’s “frequent flyer” program — meaning he was moved every three hours for weeks at a time to keep him from sleeping prior to interrogations. So just how reliable are the statements he made, either at Bagram or at Guantanamo?…

Now 23, Khadr, has been interviewed by dozens of interrogators, each time led to believe that his cooperation would spare him from violence and lead to his release. He told interrogators what he thought they wanted to hear, but that release never happened. If Khadr had been imprisoned in the United States, he would have been tried and either convicted or released long ago. But instead, Khadr has been held without trial on a secluded prison camp in Cuba for nearly a decade with little opportunity to defend himself.

More detail on Khadr’s treatment appears in a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder and Defense Secretary William Gates, jointly signed by the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, and the Juvenile Law Center.

US forces captured Khadr on July 27, 2002, after a firefight in Afghanistan that resulted in the death of US Army Sergeant First Class Christopher Speer, as well as injuries to other soldiers. Khadr, who was seriously wounded, was initially detained at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. There, according to his lawyers, he was forced into painful stress positions, threatened with rape, hooded and confronted with barking dogs.In October 2002, the United States transferred Khadr to Guantanamo, where the abusive interrogations continued, and where he has been ever since. Khadr told his lawyers that his interrogators shackled him in painful positions, threatened to send him to Egypt, Syria, or Jordan for torture, and used him as a “human mop” after he urinated on the floor during one interrogation session. He was not allowed to meet with a lawyer until November 2004, more than two years after he was first captured.

Khadr’s prolonged and abusive detention at Guantanamo Bay contravenes the legal obligations of the United States under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and is contrary to international juvenile justice standards. International law requires that juveniles are to be detained only as a last resort and that juvenile cases require prompt determination, yet Khadr was detained for more than two years before being provided access to an attorney, and for more than three years before being charged before the first military commission. After more than seven years the lawfulness of his detention still has not been judicially reviewed on the merits.

Furthermore, in violation of international law requiring treatment of children in accordance with their age, as well as segregation of children and adults, Khadr was continuously housed with adult detainees, even when other child detainees were being housed together in Guantanamo’s Camp Iguana. The abusive interrogations and prolonged detention in solitary confinement violated international law regarding both humane treatment and juvenile justice, including Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, and other prohibitions against torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

It should perhaps come as no surprise that the United States would violate these international agreements, since it routinely does so in its civilian justice system. American children are tried as adults, given life sentences, placed in adult prisons, and often locked for years in solitary confinement.

But in Khadr’s case, an argument could also be made that he shouldn’t be tried at all. ”Under international law,” Eviatar writes, ”a child captured in combat is supposed to be treated as a victim rather than a warrior, offered rehabilitation in custody and eventually repatriated home.” Khadr was nine years old when his father “dragged him from Canada to Afghanistan and put him to work helping his Al Qaeda-connected friends. Khadr has said that he never had a choice”–a position consistent with the experience of most child soldiers. As the Center for Constitutional Rights points out:

When the military commission commences…[Khadr] will become the first individual in the modern history of any international tribunal in the world, to be tried for war crimes for conduct allegedly committed as a juvenile. This ignoble precedent of prosecuting children for war crimes–something that was not done at Nuremburg after World War II, in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, or Sierra Leone, Kosovo or East Timor–will be established through American prosecution of a Canadian child.

(Khadr is not the only juvenile to be held at Guantanamo; see Celia Perry’s 2008 piece on the subject here.)

This post originally appeared on www.solitarywatch.com.

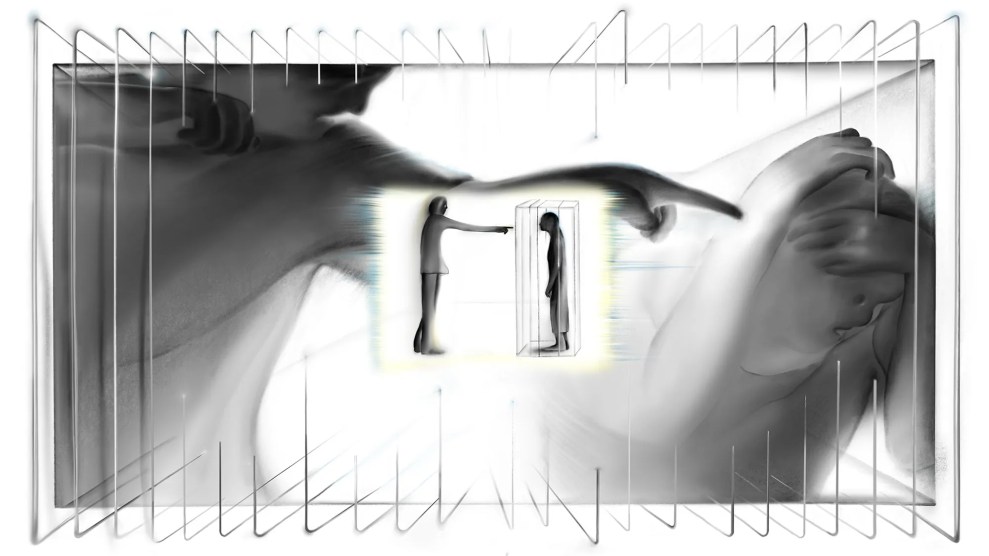

Omar Khadr during an interrogation at Gitmo in 2003.