-Mark Madeo/Courtesy of the Redford CenterNewark Mayor Cory Booker pulls out a dazzling number of personal stories, quotes, and poems that make you feel like a selfish whiner who just hasn’t pushed hard enough. “Social change is not about one big election, or one big speech,” he said Thursday to an audience of about 300 Bay Area folks who came to “The Art of Activism” event at San Francisco’s Sundance Kabuki Cinema. America has to move from “sedentary agitation” to “small, daily acts of love and kindness that people do when no one is watching,” Booker argued, clad in a black suit and tie, at times closing his eyes like a charismatic preacher at the height of a spiritual moment.

-Mark Madeo/Courtesy of the Redford CenterNewark Mayor Cory Booker pulls out a dazzling number of personal stories, quotes, and poems that make you feel like a selfish whiner who just hasn’t pushed hard enough. “Social change is not about one big election, or one big speech,” he said Thursday to an audience of about 300 Bay Area folks who came to “The Art of Activism” event at San Francisco’s Sundance Kabuki Cinema. America has to move from “sedentary agitation” to “small, daily acts of love and kindness that people do when no one is watching,” Booker argued, clad in a black suit and tie, at times closing his eyes like a charismatic preacher at the height of a spiritual moment.

How many times have you heard about the power of small acts of kindness? Yeah, one too many. But the cliche takes on new meaning when Booker makes the point through his almost-too-good-to-be-true autobiographical sketches. The media love Booker, so his story is well known: Shortly after going to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar—as well as Stanford and Yale—he started a stint as a Newark city council member at 29 and moved into a troubled public housing complex, where he lived—often without hot water and heat—from 1998 to 2006. “My parents told me I will always learn more form a woman on the fifth floor of a public housing complex than my fancy professors,” he said.

In 2002, he ran and lost* a bitter campaign against incumbent Sharpe James, another charismatic African American—but also an old-school machine politician (later indicted on 33 charges) who accused Booker of not being black enough, as well as being Jewish, gay, and funded by the KKK. Booker, who was 33 at the time, argued he was a new civil rights leader, focusing his efforts as mayor on tough crime-reduction measures while also investing heavily in prevention programs.

Booker ran again in 2006, and this time he won. Today, he is credited with reducing murders in Newark by 60 percent since he took office, while slashing the city’s chronic budget deficit before the recession hit.** (This year, Newark, like most states and cities, faces a huge budget hole, employee furloughs and layoffs.) How did Booker balance the budget before the recession hit? Prevention at the front end works, he argued last night. Booker talked to released prisoners and found that it was a sense of shame—from not paying child support, or not having a job—that drove them back into trouble. “So, we created DADS—Delta Alpha Delta Sigma—a male fraternity where single dads mentored other dads, who came out of prisons.” He bolstered that with job training programs for ex-cons and recreational facilities for youth. Newark now has a 10 percent recidivism rate, compared with about 65 percent nationwide.

“There are thousands of young kids on the waiting list for a Big Brother or a Big Sister,” he said. “We know it drives down criminal activity, increases academic success.” If every kid in Oakland and Newark had a mentor in this program, Booker argued, we wouldn’t spend billions on prisons that contribute to the growing deficit: “That’s what I call government waste.”

“There are thousands of young kids on the waiting list for a Big Brother or a Big Sister,” he said. “We know it drives down criminal activity, increases academic success.” If every kid in Oakland and Newark had a mentor in this program, Booker argued, we wouldn’t spend billions on prisons that contribute to the growing deficit: “That’s what I call government waste.”

“What keeps Cory Booker going?” the event moderator Lee Bycel asked. Booker responded by discussing the youngest victims of crime. “My worst moments are when the kid is shot, seeing the gunshot wounds, watching the bloody foam coming out of his mouth,” he said. At these moments he remembers the wisdom told to him by his parents—who were among the first black executives at IBM and filed a lawsuit to move into a white suburb. “You wouldn’t be here if there weren’t lots of people before you who faced worse moments and kept going,” he recalled. “How dare I give into cynicism and hopelessness, when I think of this history?”

It also helps when people write $100 million checks to support your agenda. In September, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg did just that to support Booker’s efforts to reform schools in Newark. Booker’s ideas of school reforms are closely aligned with those of Joel Klein and Michelle Rhee, the (now) former school superintendents of New York and Washington: Open more charter schools, give bonuses to high-scoring teachers, fire teachers who don’t improve.

It also helps when people write $100 million checks to support your agenda. In September, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg did just that to support Booker’s efforts to reform schools in Newark. Booker’s ideas of school reforms are closely aligned with those of Joel Klein and Michelle Rhee, the (now) former school superintendents of New York and Washington: Open more charter schools, give bonuses to high-scoring teachers, fire teachers who don’t improve.

But there are significant differences in their leadership styles. Rhee and Klein didn’t prioritize community approvals and failed to sell their reform ideas to most parents and students. Booker said he always ran on the platforms of community engagement and inclusion. “You can search the world over two times, but you’ll never find two people that agree on everything,” he said last night. “Real love is going beyond tolerance. It’s about knowing the other person, the other side.”

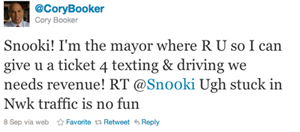

So before drawing up a plan of recommendations on how to spend his social media-funded school-reform gift, he is using social media himself (along with on-the-ground canvassers) to find out what Newark residents think about their public schools. He will publish these findings by January. Meanwhile, you can read some of the community input on Booker’s Facebook page and Twitter account—where he has over 1 million followers, nearly four times the population of his city (and more than Dalai Lama). But don’t tweet or text while you drive in Newark, or Booker will give you a traffic ticket.

[*I initially wrote that Booker won in 2002. That was wrong. He won in 2006. That’s what I get for writing on late Friday nights. Sorry. **Also, it’s important to note that Booker reduced the crime rates and recidivism, while slashing the budget before the recession. This year, Newark is facing a huge budget hole, as do most states and cities. But that shouldn’t dismiss what Newark demonstrated–a significant success in reducing government expenses (prison and crime) by prevention (youth programs, counseling and job trainings), even if this long-term approach was cut short by the recession. –h/t to MoJo reader: Fact Check 101.]