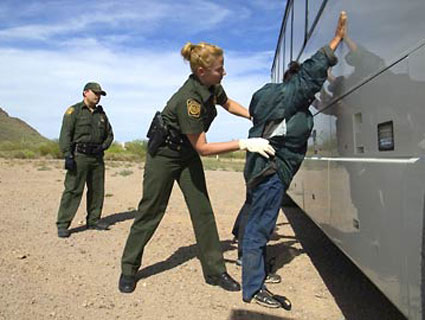

<a href="http://www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/newsroom/multimedia/photo_gallery/afc/bp/27.xml">Gerard L. Nino</a>/US Customs and Border Protection

Anyone who has ever watched a cop show on TV knows how Miranda rights work. After a suspect is apprehended, the arresting officer alerts that person to his or her rights—specifically, the right to remain silent and the right to legal counsel. The warning protects suspects from incriminating themselves and the state from later introducing inadmissible evidence.

Easy enough, right? Well, it’s never been that simple for immigrant noncitizens, whether they’re legal permanent residents or undocumented. When noncitizens are arrested by, say, local law enforcement, they are read their rights like anyone else. But when they’re picked up by immigration officers (Border Patrol or Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents), there are separate but similar Miranda-like procedures those officials must follow.

At least, there used to be. On August 11, in a surprising and precedent-setting decision (PDF), the country’s highest administrative tribunal on immigration decided that noncitizens arrested without a warrant do not need to be read their rights until after entering formal deportation proceedings—that is, until well after questioning by immigration officers. From the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) decision:

Until an alien who is arrested without a warrant is placed in formal proceedings by the filing of a Notice to Appear (Form I-862), the regulation…does not require immigration officers to advise the alien that he or she has a right to counsel and that any statements made during interrogation can subsequently be used against the alien.

The nonprofit American Immigration Council’s Legal Action Center was quick to condemn the ruling. “This decision epitomizes the substandard system of justice that’s been created and imposed on immigrants in the United States,” said Melissa Crow, the center’s director, in a statement. “The Board’s ruling renders the advisals practically meaningless and makes immigrants less likely to remain silent when questioned and less likely to assert their right to counsel.”

The case deals with a legal US resident from Guatemala who was caught by Border Patrol officers in 2004 trying to sneak his nephew into the United States. In the eight hours that passed between his arrest and the initiation of formal proceedings, the man “admitted that he knowingly used his son’s birth certificate to try to smuggle his nephew into the United States.” The man was ordered removed from the country, and the case was in appeals until the BIA handed down its ruling, deciding that the eight hours of detention did not qualify as the start of formal proceedings.

In a phone interview Wednesday, Crow said that both the timing of the ruling and the decision itself were unexpected. “To give you a criminal-case analogy, it would be like not receiving Miranda rights until indictment,” she said, adding that while it was her understanding that the lawyer in the case was planning an appeal, “there’s not a lot of wiggle room” at this stage in the process.

Bill Hing, a law professor at the University of San Francisco and a contributor to the ImmigrationProf blog, says that while the ruling is important, it might not change the reality for many noncitizens apprehended by ICE. “The truth is, even before the decision, the vast majority of people the Border Patrol or ICE believed to be deportable never got advisals of right to counsel,” he says. “Most of the time it wouldn’t make a difference. [Authorities] know the people have a criminal record or that they’re undocumented.”

But, Hing says, asking for counsel often means fielding fewer questions from immigration authorities. In some cases, then, an advisal at the time of arrest could make the difference between being deported and being released. “If they don’t have enough information to prove you’re deportable,” he says, “they give you information about counsel, or they let you go.” Without that advisal, detained immigrants are more likely to reveal incriminating information—and more likely to be deported.

Still, the decision has drawn little attention, and in a way, that makes sense. Few people understand the BIA, and last week was a big one for other immigration-related news: On Thursday, the Obama administration announced that it will review 300,000 pending deportation cases, and earlier in the week a federal judge ordered the release of hundreds of “embarrassing” emails that highlight the Department of Homeland Security’s doubts about its controversial Secure Communities program.