NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre announced his school safety task force last December.Fang Zhe/Xinhua/ZumaPress.com

On Tuesday morning, former Rep. Asa Hutchinson (R-Ark.) unveiled a 225-page report, commissioned by the National Rifle Association, on how best to prevent gun violence in schools. His task force’s conclusions: Put an armed security guard (teachers or administrations would also be acceptable) in every public school in the country, and put them through a 40–60-hour training course to give them the tools to take out a shooter. Speaking at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., Hutchinson called for more funding to help schools hire security officers and announced that the NRA would create a centralized portal to help schools develop and institute their defense plans. Hutchinson, who in December had proposed encouraging armed volunteers to stand watch at schools, said he’d concluded that was “not the best solution” after speaking with school superintendents.

Hutchinson’s shining example of school safety, which he returned to multiple times during his remarks Tuesday, was a 1997 shooting at Pearl High School in Mississippi. In that case, the school principal, who was also an Army reservist, disarmed the shooter after picking up a gun from his car. But as my colleague Mark Follman explained, the shooting had already stopped at that point.

(The report doesn’t offer specific advice as to which type of weapon might work best for school guards, but Hutchinson suggested that either a shotgun or an AR-15 would be acceptable, in addition to a more manageable handgun.)

When pressed by reporters, Hutchinson insisted that legislation currently being considered in Congress to make background checks universal for private gun sales and halt the manufacture of high-capacity magazines was irrelevant to the issue of school safety. The sweeping gun-control legislation on the verge of being signed into law in Connecticut in response to the December massacre in Newtown was, by his estimation, “totally inadequate.”

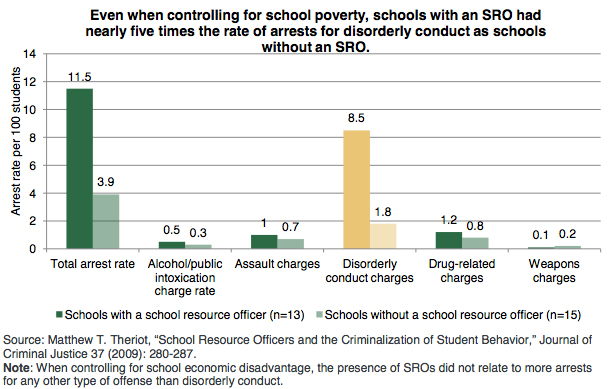

But Hutchinson only mentioned in passing one of the biggest consequence of his proposals, should they actually be adopted. A 2011 study by the Justice Policy Institute found that the evidence that school resource officers are a deterrent to crime was flimsy at best. But that didn’t mean the officers don’t have an impact. Students at schools with SROs were 2.9 times more likely to be arrested—and 4.7 times more likely to end up being charged with disorderly conduct. “All of these negative effects set youth on a track to drop out of school and put them at greater risk of becoming involved in the justice system later on, all at tremendous costs for taxpayers as well the youth themselves and their communities,” the report concluded:

Hutchinson alluded to the concerns over increased criminal charges in schools with SROs, but suggested the problem could be fixed at the local level: “This is an internal issue as to how you manage your SROs, and so you need to have clear understandings reflected in a memorandum of understanding between the school and the law enforcement agency.” But schools have always had the ability to set the terms of conduct with law enforcement, and the results haven’t been pretty. The report states briefly that “The objective of the SRO is not to increase juvenile arrests within a school.”

At the Conservative Political Action Conference last month, I watched NRA president David Keene moderate a panel on how to fix America’s criminal justice system. The conclusion among the panelists, Keene included, was we lock too many people up, and for too long. But the proposals unveiled on Tuesday, like those pushed by the NRA in the 1990s, probably wouldn’t do anything to reverse that trend; if the past is any indication, they’d just make it worse.

Read the report for yourself: