Joan Wong

Four days before Christmas 2016, Heather Ashton Miller, an inmate in Davis County Jail outside Salt Lake City, slipped while climbing down from her bunk bed. The 28-year-old, who had been arrested a day earlier for alleged drug-related misdemeanors, fell five feet and landed with a thud. When she tried to stand, she couldn’t—the fall had ruptured her spleen. As her lips turned purple, jail staffers gave her ibuprofen. It took nearly three hours for emergency medics to arrive; she died shortly after reaching the hospital.

When lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union of Utah asked for the jail’s operational standards, hoping to find out what had happened to Miller and other inmates who had died, they were told they couldn’t see them: The guidelines had been written by a contractor named Gary DeLand, who insisted that sharing his copyrighted work would jeopardize his business of developing jail guidelines and would open sheriffs to lawsuits. In April 2018, the Utah State Records Committee agreed, ruling that Davis County Jail did not need to release its guidelines because the county did not own them.

Many jails have guidelines to ensure they comply with constitutional requirements to keep inmates safe and healthy. These standards can govern virtually all aspects of a jail’s operations, from its medical care and food safety to the dimensions of its cells and mailroom procedures. “If the jail wrote and kept these standards itself, they would be public,” says David Reymann, an attorney who is representing the ACLU of Utah and the Disability Law Center in a lawsuit seeking access to the Davis County Jail guidelines. The idea that “you can contract out to a third party and put your governmental records into a black box is very troubling,” says ACLU attorney Leah Farrell.

DeLand sold his jail standards to the Utah Sheriffs’ Association for $15,000 in the 1990s, not long after his seven-year tenure as chief of the state corrections department. A self-described “Idaho country boy who never spent a day in law school,” he wrote his first jail manual around 1965 while working as a sheriff’s deputy. He found he could earn much more as a private correctional expert than as a public servant. In 2003, the Bush administration tapped DeLand to help renovate Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison, where he established a corrections academy. He says he has conducted workshops for the FBI and the Federal Bureau of Prisons and spoken at correctional trainings in dozens of states.

Since the 1970s, DeLand has written or helped develop jail standards in at least 19 states, striking agreements with counties and sheriffs’ groups to keep his model guidelines private. When lawyers requested to see the DeLand-inspired standards for Oregon’s Deschutes County Jail as part of a wrongful death lawsuit in 2015, the sheriffs’ association there claimed they were a “trade secret” like “the formula for Coca-Cola or the recipe for KFC.” Making them public “would destroy their value,” the association’s executive director said. A federal district court ruled that the documents must remain confidential. A representative of the local sheriffs’ association in Wyoming, which has worked with DeLand, explained to me that Walmart probably wouldn’t release its personnel rules to me—so why should county jails?

Jails are keeping more than their rules out of the public eye. When the Utah State Records Committee sided with DeLand, it also found that Davis County had no obligation to release its jail’s audit reports, which would reveal whether employees were complying with the operational standards. In Utah, audit reports are typically stored with software owned by Accreditation, Audit & Risk Management Security, which is helmed by Tate McCotter, whose father, Lane, ran the Utah corrections department in the mid-1990s and worked with DeLand at Abu Ghraib. Jails in more than a dozen states, from Alabama to Pennsylvania, use the company’s auditing system.

According to DeLand, ensuring that all these records stay private improves jails’ accountability. If their audit results were shared, he says, many sheriffs would not use his standards, fearing lawsuits or negative press. “The standards have had a tremendous effect,” DeLand told me. “If you can find any other state where the jails have had more success than Utah has had in preventing losses in court cases, I’d sure as hell like to know.”

Utah lawmakers obtained temporary access to DeLand’s standards after half a year of negotiating with him, but they were barred from releasing them to the public. The state corrections department announced in January 2018 that it would develop its own publicly accessible version of the jail guidelines. Amid a flurry of bad press, DeLand allowed the sheriffs’ association to post a redacted version of his standards online. He says less than 10 percent of the material is now public.

Keeping jails accountable “is not served by moving the entire process behind a veil of secrecy,” the ACLU’s lawyers argue in their suit. They also note that opening the records could shed light on why Utah has the highest rate of jail deaths in the country: At least 25 inmates died in 2016; six were in the Davis County Jail.

After Heather Miller’s death, Davis County Jail employees were cleared of criminal wrongdoing. A spokesman for the sheriff’s office defended the jail’s actions. “Our practices are sound,” he told the Salt Lake Tribune. But in a deposition, the sheriff at the time of the incident noted that the jail had gotten rid of its health care protocols about six years earlier and hadn’t developed new ones. Investigators from neighboring Weber County who looked into the incident raised a series of troubling questions: Why had the jail asked an inmate to quickly clean up the mess in Miller’s cell, which should have been preserved like a crime scene? Why hadn’t anyone notified her family?

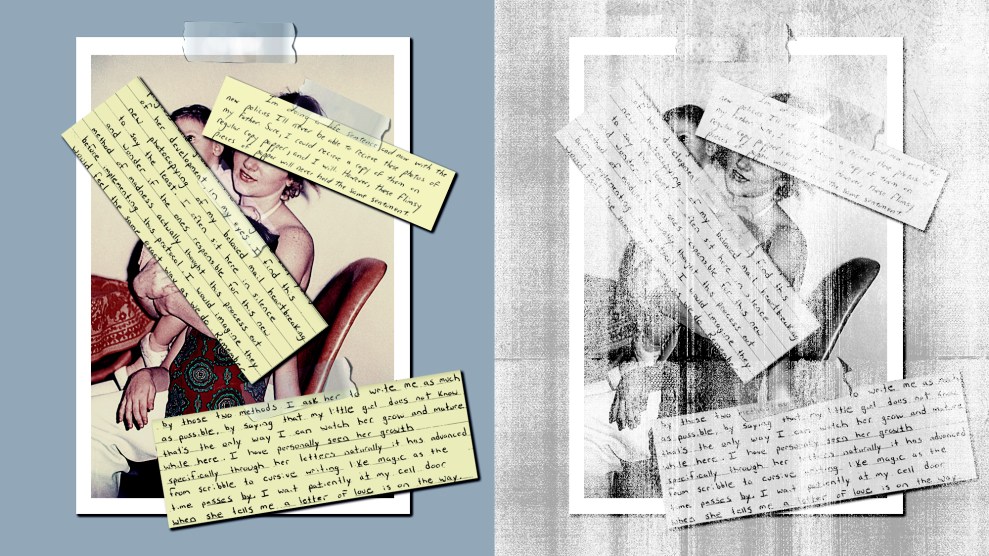

Miller’s mother, Cynthia Stella, found out about her death not from the jail, but from her daughter’s old roommate. Stella is now suing Davis County for failing to provide her daughter with adequate medical care. Early last year, she wiped away tears as she stood at a press conference to discuss Miller’s death. “I told myself I wasn’t going to cry about it and I wasn’t going to be emotional about this, but the thing is this: I do hold DeLand—or, I want answers from him.”