tzahiV/iStock/Getty

On November 2, 2004, not long after starting his sentence at a federal prison in New Jersey, Corwin Knight sat down in front of the common area’s television to watch the returns for the presidential election. He was tired of the Bush administration’s policies and hoped John Kerry would win, but he quickly grew disappointed. “I watched a little bit until I seen the number, and then I just didn’t want to watch it no more,” he recalls. “You feel powerless, not being able to participate.”

Many countries allow people in prisons to vote, but in the United States, only Maine and Vermont give all of their incarcerated people that right. Knight, who was released in 2007, wants to change that, starting with his hometown, the District of Columbia. After he got out of prison, he moved back to the capital and found work at a fast-food joint while he got his feet back on the ground. Earlier this year, after he became chair of a mayor-appointed commission that tries to improve conditions for formerly incarcerated people, he set out to convince his local officials to restore voting rights to prisoners from the jurisdiction.

For the United States, it’s a radical proposal, but it might just happen: Last week, based on recommendations from Knight’s commission, DC council member Robert White Jr. introduced a bill that would allow people from the district to participate in elections even while they’re serving time. If it passes—and the odds are good, though it may not be voted on until the fall—DC would become the first jurisdiction to restore voting rights to all its incarcerated citizens, after Congress officially stripped them of the franchise in 1955. (Maine and Vermont never took the right away.) “Those who have been convicted do not lose their constitutional protections. They do not lose their civil rights. They do not lose their citizenship,” White, whose brother was once incarcerated, said at a news conference announcing the legislation. “Why, then, would they lose their most fundamental democratic right?”

During America’s colonial era, in keeping with an English tradition known as “civil death,” people convicted of certain serious offenses often lost the right to vote in prison. After the American Revolution and later, after the Civil War, some states passed laws to disenfranchise anyone convicted of a felony. This trend became more extreme during the Jim Crow era, after the Fifteenth Amendment gave African American men the right to vote, as more states codified felony disenfranchisement or made these policies harsher—sometimes with the explicit purpose of keeping black people, who are more likely than whites to be targeted by the police and imprisoned, off the voter rolls. A drafter of Virginia’s 1902 Constitution argued that stripping prisoners of their voting rights would help “eliminate the darkey as a political factor.” Today, felony disenfranchisement laws vary from state to state: Some are lifetime bans, while others keep people from voting until they finish their prison sentences or parole or during probation. About 6.1 million people nationally can’t vote because of these laws, and about 36 percent of them are African American. According to Emily Tatro of the Council for Court Excellence, a local nonprofit, who cited data from a local court services agency, about 96 percent of people convicted of felonies in DC are black.

In recent years, some states have passed laws to eliminate lifetime voting bans for felons, allowing more people to participate in elections after they’ve finished their sentences. But extending the franchise to prisoners themselves has been controversial. At a CNN town hall for presidential candidates in April, Sen. Bernie Sanders told a crowd that regardless of a person’s crime, he believed prisoners should be allowed to cast a ballot. But other Democratic candidates have shied away from the idea. “Part of the punishment when you’re convicted of a crime and you’re incarcerated is you lose certain rights, you lose your freedom,” Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, said during the town hall, “and I think during that period it does not make sense to have an exception for the right to vote.” Some candidates have hedged—former Rep. Beto O’Rourke suggested making an exception so nonviolent offenders can vote, while Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris haven’t said exactly where they stand on the issue. According to one poll, a majority of Americans don’t support extending the franchise to prisoners.

This year, lawmakers in Massachusetts, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Virginia introduced legislation to let prisoners vote, but none succeeded. But White’s Restore the Vote Amendment Act has a good chance of passing in DC, which, compared with other jurisdictions nationally, has some of the fewest voting restrictions for people with felony records: They are automatically reenfranchised when they are released from prison, as is the case in about 14 states. In DC, people awaiting trial or serving time in the local jail for misdemeanor offenses can also cast a ballot. “This is the last frontier in voting rights here,” says Tatro. The bill was co-introduced by every member of the DC Council, and it has the support of DC Attorney General Karl Racine. It would be subject to congressional review, like any local law passed in DC, but the Democratic-controlled House is unlikely to oppose it.

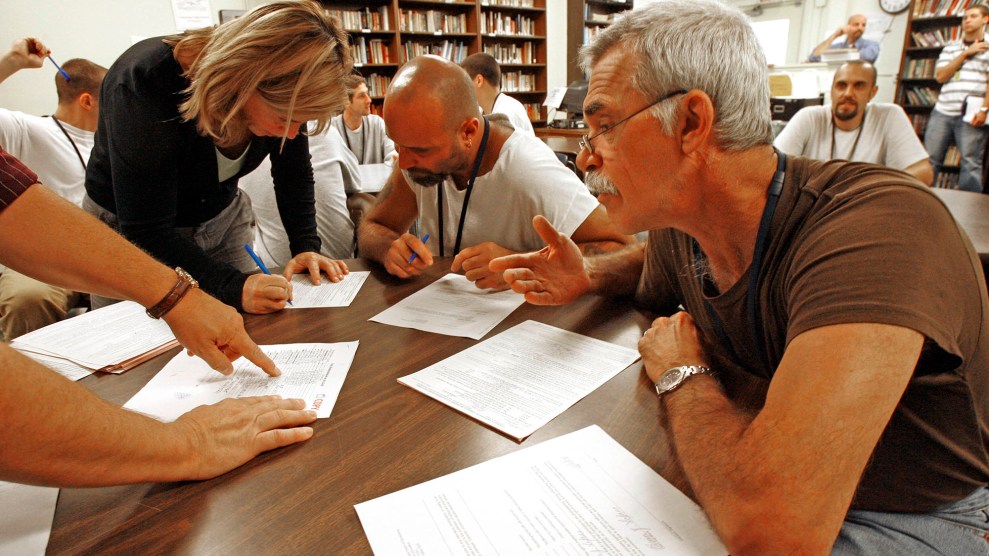

If it passes, DC prisoners would vote by absentee ballots, like Maine and Vermont prisoners do. A spokesperson for the Federal Bureau of Prisons confirmed that the agency already has policies in place to facilitate this. But there would also be some differences: DC does not have any state or federal prisons in its jurisdiction, so its residents with felony convictions are spread out in federal prisons in different states. “We need to make sure, because the people from DC are so scattered across the country, that they are getting access to voter registration and voting guides in a timely fashion once this kicks in,” Tatro says. Even in Maine and Vermont, where prisoners are clustered in the same facilities, an investigation by the Marshall Project suggests that voter participation for incarcerated people is low, partly because poor literacy rates and a lack of internet access make it harder for prisoners to keep up with the news.

But these challenges don’t diminish the practical and philosophical arguments in favor of extending the franchise, says Marc Mauer of the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group. Allowing inmates to vote may even have public safety advantages, given that it can make people feel more connected to their communities, something that experts believe may help reduce recidivism. What’s more, New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie points out, the political system could benefit from inmates’ weighing in on policies. “Their votes might force lawmakers to take a closer look at what happens in these institutions before they spiral into unaccountable violence and abuse,” he writes. Mass incarceration costs taxpayers $182 billion every year, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, and US prisons are plagued by widespread reports of medical neglect and dangerous conditions. Prisoners, advocates say, should be allowed to vote for the public officials who will affect their safety.

On Election Day in 2008, not long after he got out of prison, Knight walked to a polling station in DC with his mom and voted for Barack Obama. That night he sat down again to watch the returns. “It was a wonderful thing to look at the TV and see the board light up with Democratic votes,” he says. “I think everyone cried that day, just to see Obama win. And then I felt so good to be a part of history. It felt so good.”