Mother Jones illustration; Getty

In 2010, Dana Gallop, a Boston gang member accused of murder, was waiting for his trial in a Rhode Island prison when a fellow inmate assaulted him with a razor. The attack left scars across Gallop’s face. He tried to sue, alleging that the inmate had warned a correctional officer about the ambush, and that the officer had left the scene to let it happen.

But when his case made it up to the state Supreme Court in 2018, there was a problem: The court ruled that Gallop couldn’t legally sue because he was dead.

Well, sort of. Under a century-old law, Rhode Island classifies everyone serving a life sentence in the state as “civilly dead,” meaning they have absolutely no civil rights. Unlike other prisoners, they can’t sue or raise complaints in state court, even if they’ve been mistreated or abused. They can’t get married or divorced, they lose rights over their children, and they can’t own property in their name or sign a contract. In these matters, as the law puts it, they are “deemed to be dead in all respects, as if [their] natural death had taken place at the time of conviction.” It doesn’t matter if they are eligible for parole and will eventually leave prison.

Most states got rid of laws like this years ago, or don’t enforce them. Now a movement is building to get Rhode Island’s civil death law struck down. At least two lawsuits argue it’s unconstitutional, and that states can’t strip people of federally guaranteed fundamental rights.

Civil death, as a concept, traces back to ancient Greece and Rome, where people awaiting execution for crimes were prohibited from appearing in court, voting, making public speeches, or serving in the army. Later, Germanic tribes in Europe practiced “outlawry,” declaring that people convicted of some crimes were “outside the law” and had no civil rights. England eventually adopted civil death as part of its common law, and colonists later brought the concept to America, where states would codify versions of it with their own statutes. In 1871, a Virginia court ruled that a person convicted of a felony “forfeited…all his personal rights except those which the law in its humanity affords him. He is for the time being a slave of the state.”

Under early English common law, civil death was reserved for people convicted of felonies, and just about everyone with a felony was awaiting execution. But later in the United States, when long prison terms replaced execution as a punishment for some felonies, many states expanded civil death to apply to life sentences. This led to some conundrums. A Harvard Law Review article in 1937 argued it was problematic to treat someone as dead when they would one day be eligible for parole, as many lifers are, and leave prison. The article cited the case of a New York man whose marriage dissolved because of a civil death law; after he was sentenced to life, his wife legally remarried without filing for divorce. When he later got out of prison, a court would not allow her to annul the first marriage because he had been “dead.”

Civil death laws also stripped prisoners of their possessions, which meant they had no resources to get back on their feet once they returned to their communities. For this reason and others, states began repealing these laws in the mid-20th century, according to Gabriel Chin, a law professor at the University of California-Davis who wrote about the issue in 2012 in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review. “The court cannot fail to note that the concept of civil death has been condemned by virtually every court and commentator to study it over the last thirty years,” a three-judge Missouri court ruled in 1976, holding that the state’s law was unconstitutional. “It has been characterized in recent years as ‘archaic,’ ‘outmoded and medieval,’ ‘an outdated and inscrutable common law precept,’ and ‘a medieval fiction in a modern world.’”

Of course, even in states that repealed their laws, the idea of civil death lingered. Prisons continue to restrict certain civil rights, like voting, and even after people get out, those with felony records are often barred from serving on a jury, running for office, or holding some other jobs.

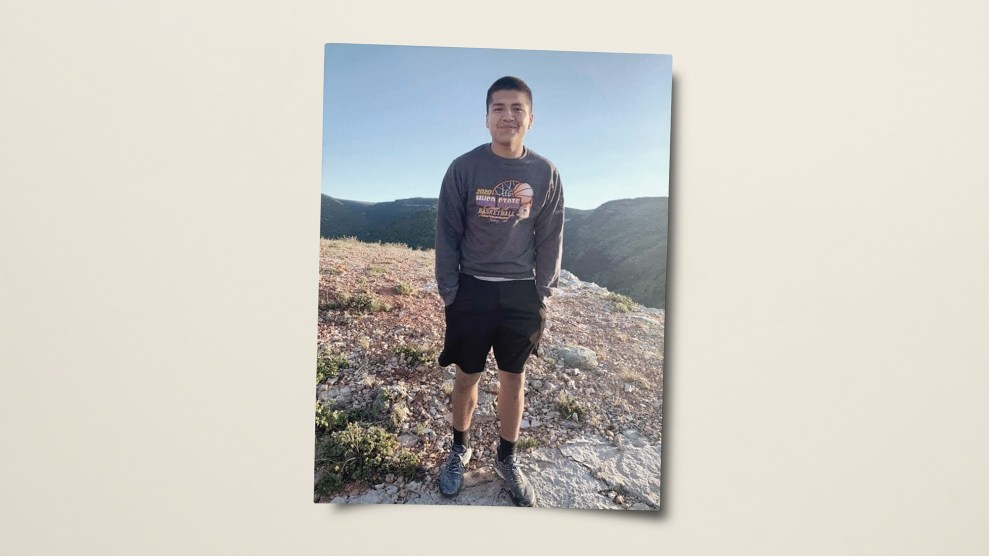

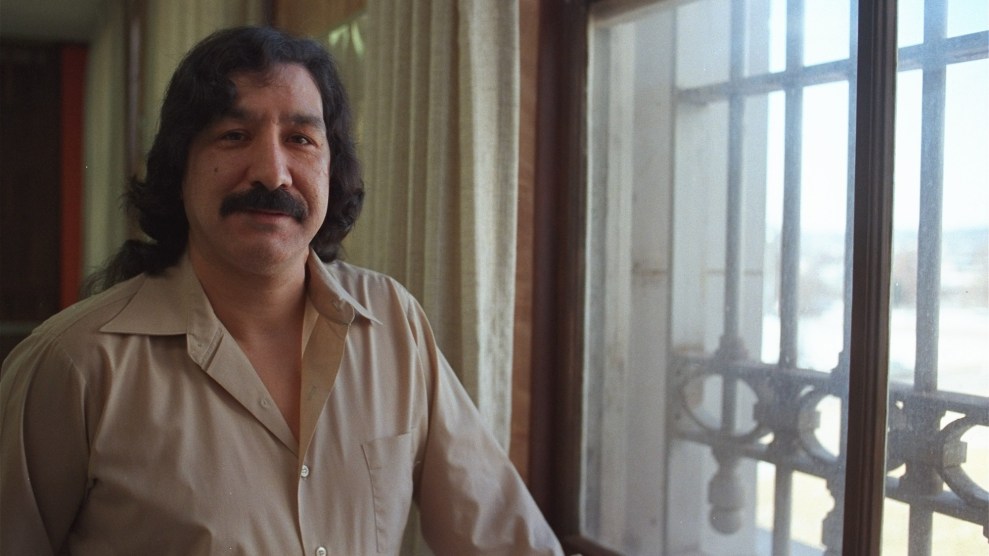

New York and Rhode Island are the only two states that never got rid of their civil death statutes. (Neither did the US Virgin Islands.) But Rhode Island is the only place where civil death is still enforced, says Sonja Deyoe, an attorney in the state who for years has fought against the statute. She represents lifers like Joshua Davis, who, because of the law, was unable to sue officials at the Adult Correctional Institutions after a prison nurse gave him an insulin shot last year that was contaminated with the blood of other inmates, potentially exposing him to life-threatening viruses like HIV or hepatitis. She also represents Cody-Allen Zab, a lifer who similarly had little recourse after he was burned in the same prison, when he brushed up against an exposed steam pipe in the maximum security facility near the phones. “The state could choose not to feed these individuals, deny them medical care, torture them, or do anything short of execute them,” and they would “have absolutely no redress available to them from the State Court,” Deyoe wrote in a lawsuit in June on behalf of Zab. Blocking lifers from courtrooms makes it harder to keep prisons accountable for neglect or abuse, she adds. “There is nothing to suggest that…the State should get a free pass on the wrongs committed by the Department of Corrections and its employees against these inmates,” she wrote.

The suit argues that the civil death statute is unconstitutional, and that states cannot strip people of federally guaranteed fundamental rights, such as freedom from cruel and unusual punishment. In cooperation with the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island, Deyoe filed another lawsuit this month on behalf of Davis and a second inmate, again contending that the statute violates the First, Fifth, Seventh, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments. “The Civil Death Act, in treating plaintiffs as if they were dead and denying them basic civil, statutory, and common law rights and access to the courts, imposes an excessive and outmoded punishment contrary to evolving standards of decency,” it argues.

In defense of the law, attorneys for the corrections department argue that lawmakers have broad authority to make decisions about punishments, and that the state Supreme Court previously declined to repeal the civil death law. They also point to the serious nature of Zab’s crime: “It is not irrational for the Legislature to determine that a criminal who set fire to the home of a 95-year-old man and killed him should not be permitted to collect monetary damages from the State for touching a hot pipe,” they wrote in court documents.

Between 220 and 240 prisoners in Rhode Island are now serving life sentences, some with the option of parole and some without. According to Deyoe, courts in the state have not yet clarified whether people regain their civil rights while they are on parole. She says no freed lifers have wanted to press the issue in court for an answer because they are worried about ruffling feathers so soon after leaving prison.

In 2007, Rhode Island lawmakers passed a bill to repeal the civil death statute, but then-Gov. Donald Carcieri (R) vetoed it. “Persons who are sentenced to the remainder of their natural lives in prison are there because they have been found by a jury of their peers to have committed the most serious possible crimes against society, in many cases offenses that have stripped another human being of his or her life,” he wrote. “The loss of property, and even the right to marry, is not unreasonable.” Similar repeal bills have been introduced since 2014, including this year, but none have passed.

After losing at the state Supreme Court in 2018, Gallop, the man scarred from the razor ambush, asked a lower court to consider another complaint that he filed, alleging that his federal constitutional rights were violated when correction officials failed to stop the attack. The guard “had a duty to keep me safe,” Gallop testified back in 2015. But the court, arguing too much time had passed, refused to hear the case.