Chicetin/Getty

Kristy Johnson was 6 years old in 1969, when her father, an educator employed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, began sexually abusing her at their home in Utah. Her mother discovered what was happening and sought help from their local Mormon bishop. But according to a civil lawsuit Johnson filed against her father last year, the bishop did not contact police, instead handling the abuse “as a matter of sin, only.”

The same thing happened each time the abuse was reported to church leaders, according to Johnson’s complaint. One bishop instructed her father to “clean up his act,” she tells me. Her father was reassigned to different towns. And the church never called the cops, the lawsuit alleges. “They didn’t want the word to get out, because of who my father was,” Johnson says. “Because it would make the church look bad. That was their main concern.”

Despite the Mormon Church’s quiet attempts to counsel her father, the violence allegedly continued for about 15 years. According to the lawsuit, the attacks escalated from fondling to beating and rape, stopping only when Johnson left home at age 21 for her church mission. Only later, once she learned her sisters had also been sexually abused, did she decide to go to the police. It was the first time she’s aware of that law enforcement had ever been contacted. Her father, Melvin Kay Johnson, was not arrested; he has since admitted to “inappropriate sexual conduct” with his daughters when they were older and settled the lawsuit against him.

For decades, Utah has required any person with knowledge of child abuse or neglect to report it to the police. Yet built into that law, and most states’ mandatory reporting laws, is an exception: Clergy members who learn of these crimes through a private, spiritual conversation with the perpetrator are not required to notify the authorities.

Lawmakers in Utah and New York are currently pushing to eliminate the confession exception, which they say has allowed religious institutions to cover up sexual abuse by clerics and congregation members. And they’re gearing up for battles against the Catholic and Mormon churches, both of which opposed a similar proposal that has stalled in the California state Capitol.

“I know this is already going to be a fight,” says state Rep. Angela Romero of Salt Lake City, who recently announced that she will introduce a bill to eliminate the confession exemption during the next legislative session. Romero says her bill is influenced by Johnson’s experience and the stories of other abuse survivors who feel that the exemption contributed to the mishandling of their cases.

But she knows the proposal will be a tall order in Utah, where the Mormon Church exerts a strong influence in state government. Romero is one of just 13 members of the state legislature who are not Mormon; she was raised Catholic and is familiar with the many stories of how Catholic authorities failed to alert law enforcement about abusive priests. “I want to ensure that that can’t happen,” Romero says. “If we mandate teachers to report, if we mandate other professions to report, why aren’t we mandating religious leaders to report as well?”

The reason is “clergy privilege,” a special legal protection akin to attorney-client privilege or doctor-patient privilege that exists in all 50 states. Intended to foster relationships between religious leaders and their congregants, clergy privilege shields clerics of all faiths from being forced to testify about certain conversations they conduct in their spiritual capacity. In the United States, clergy privilege statutes date back to 1829, when New York passed a law following public outrage over a court decision that forced a Protestant minister to testify. Since then, clergy privilege has been invoked in cases involving nearly 50 religious groups, from the Roman Catholic and Mormon Churches to Santeria and the Salvation Army, says Christine Bartholomew, an associate law professor at the State University of New York-Buffalo.

Bartholomew, who has reviewed every clergy privilege claim made in US courts between 1811 and 2017, says the laws theoretically cover any conversation in which a cleric offers “comfort, aid, or solace” to another person. “For instance, you go to park your car,” she says. “You see your pastor because he’s parking his car next to you. He gives you a hug. ‘How are you doing today? It looks like it’s been a rough day.’ Anything you say next? Privileged.”

But her research yielded a surprising discovery: Despite the clergy privilege laws’ broad protections, clergy members often wanted to testify. So they sought out loopholes in religious doctrine or church practice that allowed them to testify about crimes without technically violating the privilege. In 1997, a Jesuit priest reconsidered the nature of a murder confession he had heard eight years earlier, reclassifying it as a “heart-to-heart” talk so he could help exonerate two men wrongfully imprisoned for the killing. Last year, another priest spoke to police officers about a man who had made an admission that he had killed his ex-wife, explaining that the man had never specifically asked for the sacrament of confession.

However, there was an exception to this trend, Bartholomew says. In cases involving child abuse by clerics, clergy members tended to push for blanket protections, even claiming that clergy privilege covered not just confessions but also church documents and other communications.

This broad interpretation of the privilege matches Johnson’s experience. When her father confessed the abuse to Mormon Church leaders, she says, they “didn’t do anything.” But they also didn’t alert law enforcement when they learned about the abuse from her mother, her lawsuit alleges. “They’re even skipping that step,” Johnson says. “Even when the victims come to them.” The Mormon Church says it has a “zero tolerance” policy for child abuse and maintains a hotline “to connect Church leaders with a professional counselor and legal professionals and to ensure compliance with abuse reporting laws.”

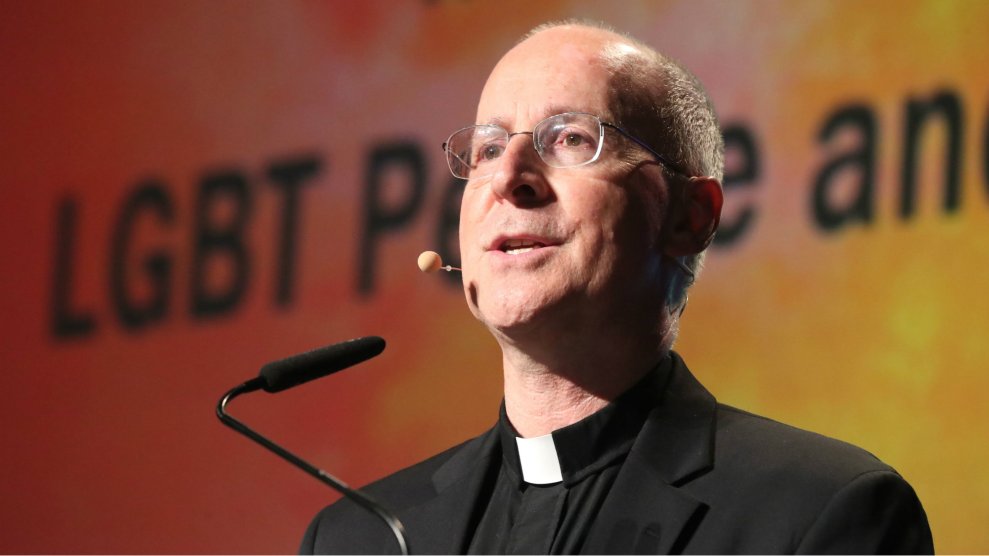

Clergy privilege isn’t absolute everywhere. Six states—New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Texas, and West Virginia—have passed laws voiding the privilege in cases of child abuse. California state Sen. Jerry Hill, of San Mateo, attempted to add his state to the list this year, introducing a bill that would have required clergy members to report known or suspected child abuse when they learned of it during a “penitential communication.” A legislative committee later narrowed the bill to only apply to confessions made by other clergy or church employees. It was approved by the California Senate in May.

But the bill generated enormous pushback among Catholics, who consider confession a sacrament. Priests who violate its confidentiality may be excommunicated. “When something is inviolable, as the sacrament is, it’s not as if one violation is okay,” says Father Pius Pietryzk, the chair of pastoral studies at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park, California. Pietryzk, who is also a lawyer, believes Hill’s bill would be unconstitutional and would give the government say over the innermost workings of the church. After the Senate vote, Bishop Michael Barber of Oakland wrote to his diocese, calling the bill “an attack on the very heart of our faith, our freedom of religion and against the protections given to all Americans by our Constitution.” He added, “I will go to jail before I will obey this attack on our religious freedom.”

Steve Pehanich, communications director for the church’s state policy arm, argues that practically speaking, there is no evidence that the bill would make a difference. “Pedophiles are notoriously secret people,” he says. “They’re really not going to confession. There’s no evidence that they are.” Pehanich also says the bill would interfere with a more than thousand-year-old religious practice. “It’s a Catholic, faithful person speaking directly to God, through the priest,” he says. “People seeking spiritual guidance, spiritual forgiveness, they’re doing it for a reason. You have to be free to be able to continue to do that.”

Catholic leaders across the state urged members of their dioceses to write letters to lawmakers; the state Assembly’s public safety committee tallied opposition from more than 125,000 individuals.

On July 9, Hill put the bill on hold while he and his staff reconsider strategy. “None of our freedoms are absolute,” Hill says in response to the argument that his proposal would have violated the First Amendment’s protections for religious freedom. He points to a 2015 law that eliminated the personal-belief exemption that some California parents had used to avoid vaccinating their children. Opponents of that law also argued it violated religious freedom—an argument that failed before a state appeals court last year. “When the greater good of society is harmed more by that practice, then society steps in,” Hill says.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers in New York are gearing up for what they expect will be a similar fight. New York is one of seven states in which clergy are not considered mandatory reporters of child abuse. In March, Assemblymember Monica Wallace introduced a bill that would clarify that the state’s clergy privilege law does not protect confessions of child abuse or mistreatment. The bill would also increase penalties for people and organizations that do not report abuse, making second offenses a felony. “I do think there are legitimate doctrinal reasons for having secrecy in a confessional,” Wallace says. “But when you’re talking about children, you’re talking about the most vulnerable who cannot fight for themselves.”

Wallace, who worked with Christine Bartholomew to write the bill, sees it as the “next logical step” after the state’s Child Victims Act, which was signed into law in February. That law, which lengthened the statute of limitations for child abuse survivors to sue or press charges against their abusers, had been blocked for more than a decade by Republicans in the state Senate backed by the insurance industry and Catholic Church. (Law firms representing clergy abuse survivors reported that the church spent nearly $3 million to fight the bill between 2011 and 2018.) After Democrats took control of the state Senate last November, the bill was permitted to come to a vote in that chamber. It passed unanimously.

State Sen. Brad Hoylman, who cosponsored the Child Victims Act, introduced a version of Wallace’s bill in the New York state Senate in June. He’s hoping that newly permitted lawsuits from survivors will shed light on how religious institutions have hushed up allegations of child abuse. “Those coverups—if they do come to light—could have been avoided if you have a mandatory reporting law for clergy,” he says.

Kristy Johnson says she is willing to go anywhere to make the argument against granting clergy the privilege of silence in child abuse cases. “Do you want me to testify? Do you want me to be at a hearing? Whatever you need, we are here.” She’s participated in a documentary about confronting her father and has called for change in the Mormon Church, of which she is no longer a member. She urges other survivors to speak out—but to law enforcement, not religious officials. “Don’t go to your clergy,” she says. “Don’t put that burden on these men, who are just men. Even if they’re trained. They’re just men.”