The catalyst for Faribault, Minnesota’s crime-free housing law came one night in October 2013, when more than a dozen residents gathered at a city council meeting to air concerns about the state of their historic downtown. They were worried, as a local reporter recounted, about public safety and building codes. But not far from the surface, the complaints centered on the growing community of Somali immigrants, many of whom lived around the central business district of this city of 23,000 people, about an hour south of Minneapolis.

Business owners were frustrated that Somali men often gathered on sidewalks to talk, blocking access to storefronts. One parent said there was now “an element of fear among the kids—especially the girls.” Shopkeepers said their businesses were infested with cockroaches because the tenants living upstairs were leaving out food. “These bugs are not indigenous to Minnesota,” Tami Schluter, who owned a bed-and-breakfast, said in a statement to the council. But, she continued, “Who wants to admit their business has bugs? Complaints about other problems gets the business owner labeled as a bigot!”

Asher Ali, a Somali community leader, tried to respond to the claims being tossed around. “When you see me talking to friends and you feel scared, I cannot treat that problem,” he said. But his words did little to abate the grievances. “Please do something for the people I cater to,” said Janna Viscomi, an owner of Bernie’s Grill, who had previously complained to the Faribault Daily News about people standing in the way of her customers. Schluter blamed landlords for not taking better care of renters who might not know their legal rights. “We need to do a better job,” she told the council, “of educating incoming tenants as to our culture and our laws.”

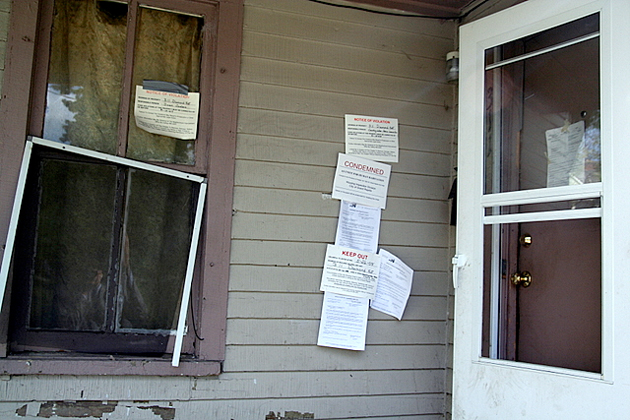

Police Chief Andrew Bohlen thought the business owners were overlooking a more pressing safety issue. In a memo he sent out before the meeting, he assured council members that crime levels weren’t rising downtown, and that a proposed measure to stop loitering would likely be “unenforceable.” The real issue, he believed, was a few “problem tenants” at three rental properties outside of the downtown area, who together had been the subject of 103 complaints in one year for disorderly conduct and other disturbances.

One of those tenants was Thelma Jones, an African American health aide who rented a five-bedroom house with three of her kids and a grandson. Jones’ neighbors, who were white, had called the police on her family at least 82 times in two years, complaining about barbecues and kids jumping on a trampoline. The neighbors also griped about her yard, which they said was messy. Some suspected that members of Jones’ family were using drugs.

None of these incidents led to a criminal conviction. But nuisance calls like these, the police chief believed, were draining resources from his department. As he and a second city official wrote in another memo, “problematic tenants” would push “quality tenants” away and “ultimately change the landscape of tenants renting within Faribault.” He urged the council to adopt guidelines laid out by the International Crime Free Association, which were already in place in St. Paul, Rochester, and dozens of other Minnesota cities. The rules, known as the Crime Free Multi-Housing Program, make it easier for landlords to remove certain renters. Landlords who receive certification through the program are taught to use a lease addendum that allows them to evict anyone suspected by police of engaging in criminal conduct in or around their homes. They attend an eight-hour training, run background checks on prospective tenants, and are encouraged to evict an entire household if a single member or guest is thought to be breaking the law.

After more meetings, in June 2014, the council voted unanimously to pass a sweeping housing law that capped the number of tenants in rental units and required landlords to adhere to a version of the Crime Free Multi-Housing Program. Landlords who didn’t could be charged with a misdemeanor, fined, and jailed for up to 90 days.

Faribault’s new law, which applied to private rentals, mirrored controversial federal legislation that already applied to public housing tenants. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Anti–Drug Abuse Act, which used evictions to deter drug dealing and other criminal activity in publicly funded housing. Two more bills, signed by George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, strengthened the initial law, creating what’s known as the one-strike policy. If, for instance, a teenager commits a minor offense like smoking pot in or around her federally subsidized apartment, her family may be booted from their residence. In May, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) raised concerns about this rule during a hearing with Housing Secretary Ben Carson, arguing that it unfairly punished entire families and disproportionately harmed people of color. Carson suggested he’d be open to reforming it. In July, Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) introduced legislation that would eliminate the one-strike policy.

Far less attention has been paid to the crime-free housing programs for private rentals that hundreds of cities and towns have adopted over the past three decades. Some cities have implemented the program as a set of voluntary guidelines for landlords, while others, including Fort Worth, Texas, and San Bernardino, California, have made versions of these rules into law. The expansion of these provisions into the private housing market is “very, very troubling,” says Katy Ramsey, a former tenants’ attorney who teaches law at the University of Memphis. Focusing on evicting people “who might be any hint of a threat” is “probably just a proxy for other things that people consider to be undesirable.” Crime-free housing programs, she wrote recently in the UCLA Law Review, put “an unprecedented number of people, many of whom are low-income people of color, at risk of eviction and homelessness.”

The International Crime Free Association, whose founder developed the model that most crime-free housing programs are based on, estimates its guidelines have been implemented in more than 2,000 cities in 48 states since the early 1990s. It says its program teaches landlords how to “keep illegal activity off rental property,” a goal it presents in stark terms. A training manual used by multiple cities that have adapted its program refers to criminals as a “two-legged urban breed of predator.” Criminals are “like weeds,” it continues. “As a weed grows, it roots, it sprouts and it chokes out healthy plants.” The association’s founder boasts that the program helped one couple renovate their property by evicting the occupants of 67 out of 71 units.

Police and city officials maintain that these programs work. The International Crime Free Association claims properties that have implemented its guidelines experience, on average, a 75 percent reduction in crimes or 911 calls. Crime did fall in Faribault after the crime-free housing law passed, in part because it was “driving problem tenants out of town,” says Paul Reuvers, an attorney for the city. RuthAnn Eide, a crime prevention coordinator at the St. Paul Police Department and a committee chair of the Minnesota Crime Prevention Association, said she had never seen the program enforced in a discriminatory way. “Maybe decades ago in the dark ages, when personal and institutional racism was running rampant,” she said. “It’s just not like that anymore.”

Thelma Jones, whose family was evicted from their home, recalls that a neighbor told her to “go back to where you came from.”

Andy Richter

Yet these programs’ critics argue that, decades after redlining prevented many African Americans from owning houses, crime-free housing policies have become blunt tools for forcing people of color out of neighborhoods, or for preventing them from moving in at all. Last year, Thelma Jones and six other Faribault residents, with help from the American Civil Liberties Union, sued Faribault in federal court, claiming that the city’s rental housing law was passed “with the express intent and purpose to discriminate against Somali and Black people.” If the case proceeds to trial early next year, it will be the first time a judge has had to weigh in on whether a codified version of the program violates the Fair Housing Act.

The idea for a crime-free housing program had been floating around Faribault for years. During a review of the police department in 2008, a consultant suggested the city adopt it. That recommendation came just as the city’s Somali community started to expand. From 1993 to 2005, while civil war raged in Somalia, about 12,000 refugees from the country relocated to Minnesota. By 2009, roughly 175 were living in Faribault. Nearly 900 more moved to the city over the next seven years, and many found work at the Jennie-O meat factory. For years before the Somalis arrived, and Cambodian refugees and Latino immigrants before them, Faribault had been about as white as a town could get. (In 1924, the Ku Klux Klan’s Minnesota chapter held its first convention on the fairgrounds.) From 2000 to 2010, the number of black people in the town more than tripled, to almost 8 percent of the population. Today, more than a fifth of the city’s population are people of color.

Some residents welcomed the Somali newcomers, and nonprofits sprang up to connect them with English classes and jobs. Many Somali families settled around the city’s small business district, where rents were cheap. Then-Mayor John Jasinski, who was pushing a redevelopment scheme for the downtown area, had some concerns. “The family makeup of having kids and things like that living downtown isn’t the best,” he said in a television interview in 2016. “You’ll drive by and see maybe them playing kickball in a parking lot, and people get offended by that.” He suggested trying to make the downtown area “a little bit more vibrant” with fancier, lower-density units as well as finding the immigrant families housing elsewhere.

As part of the redevelopment plan, the city offered loans to property owners who renovated their buildings and followed the new crime-free housing program. In a video produced by the city, Jasinski and then–City Administrator Brian Anderson said they were putting more police on the streets to support the program, and, as Anderson put it, “get rid of” some of the “undesirable” people in town. Viscomi, who was elected to the city council after the housing law passed, said in an interview in late 2016, while she was running for mayor, that Faribault needed to attract wealthier families and businesses or it would “flip like Detroit in a few years.”

Not long afterward, in November 2016, Donald Trump held an election rally in Minneapolis. “Here in Minnesota you have seen firsthand the problems caused with faulty refugee vetting, with large numbers of Somali refugees coming into your state, without your knowledge, without your support or approval,” he told the crowd. “You’ve suffered enough.” After Trump took office, some residents in Faribault said they were relieved by his “travel ban,” which had suspended refugee resettlement. “I think slowing things down would be good,” Viscomi told the Minneapolis Star Tribune when asked about the ban. “I don’t want to see families separated, but in the other regard, there needs to be somebody saying, ‘Hey, let’s breathe here.’”

Shortly after Faribault’s housing law went into effect, Rukiya Hussein, a Somali immigrant whose husband worked at the meat plant, gave birth to a baby girl. A month later, according to court documents, she got a letter from her landlord saying her family needed to move out of their three-bedroom apartment because there were now six kids in the household, one more than the occupancy limit allowed. The experience prompted Hussein to join the ACLU lawsuit.

Abdi Hussein (no relation to Rukiya Hussein), who works at a halal market, says he couldn’t find an apartment big enough for his wife and five kids after his landlord asked them to leave their two-bedroom place. They ended up renting a house they couldn’t afford. As a result, he sent his wife and kids to Kenya, where they will stay until he can save enough money to buy a house in the city. Hussein says he feels fairly welcome in Faribault. But he knows many Somali families affected by the housing law, including more than a dozen that have moved away altogether.

Ali Ali, one of the plaintiffs in the case at the Somali Community Resettlement Office.

Andy Richter

Rukiya Hussein, another plaintiff. One month after having her last child she was given an eviction notice.

Andy Richter

The city has not tracked how many people have been evicted because of the occupancy limit imposed by the housing law. Yet Alejandro Ortiz, an ACLU attorney who is leading the case against Faribault, notes that many Somali families, which are more likely to be larger, have been forced out of their homes by the limit. The ACLU’s lawsuit against the city asserts the law was intentionally implemented to restrict the number of Somalis in Faribault. The suit cites comments made by Anderson and Viscomi as evidence that the law was passed with discriminatory intent.

By December 2017, six property owners were on probation for violating Faribault’s rental housing law, and one had been jailed for noncompliance. The crime-free housing program had led to the eviction of 90 “problem tenants,” according to a city budget document. Michael Tousignant, a landlord in Faribault, said the police forced him to evict a mother with three kids because her husband was caught dealing cocaine, even though the husband was not on the lease. She was also arrested, but all charges against her were dropped, and Tousignant says she had been a good tenant. He recalls that when he questioned the police about the eviction, which he believed was unfair, an officer “basically said, ‘I threw her out because I wanted to,’” and then wrote him a ticket under the rental housing law. (The city denies that an officer said this.)

Thelma Jones, the renter whose neighbors kept calling the police on her family, was evicted in early 2017, around the time prosecutors charged her landlord with not properly registering the property or attending the eight-hour training, according to the lawsuit.

Jones, Hussein, and the other tenants suing the city argue that Faribault adopted the rental housing law with the intent of removing families of color from within its limits. And regardless of its intent, the plaintiffs argue, the law disproportionately harms people of color. Black people are much more likely than white people to rent homes; 90 percent of Faribault’s black households are renters, compared with 28 percent of white households. Black people are also more likely to be arrested and incarcerated, which makes them more likely to be flagged in a background check or kicked out of their homes under one-strike policies. (In 2015, nearly 45 percent of people arrested for disorderly conduct in Faribault were black.) “The crime-free housing programs extend injustices in the criminal justice system and import them into housing,” says Ortiz.

As of late last year, according to an attorney for the city, 21 percent of the people evicted due to the crime-free housing program were black; 11 percent of the city’s population was black in 2017. The ACLU says an even higher number of black people may have been affected by the program, because the city came up with these statistics only after the lawsuit was filed, in part by asking a police officer to recall the race of evicted tenants. The city has not kept any data on the race of people evicted due to the occupancy limit or denied housing because of rental application rejections triggered by background checks.

A slide from a presentation that the city of Faribault used to train landlords. The presentation was obtained by the ACLU during legal proceedings.

Attorneys for Faribault say the allegation of racial discrimination is “frivolous, vexatious, and a sham,” and that the rental housing law’s goal is to ensure people have safe and sanitary homes. The city also denies that it encouraged landlords to reject any potential tenants with criminal records; the ACLU notes that the Department of Housing and Urban Development has advised against such policies since 2016. The city says property owners still have the ultimate say about who they rent to. However, a training document the city gave to landlords lists “criminal history” among the “suggested criteria” for rejecting rental applicants. A PowerPoint document used to train landlords as recently as 2017 states that “a criminal record does not bar you from renting to an applicant,” but adds that the crime-free housing law will be enforced against landlords who sign leases with tenants when a “criminal history is evident.” It then spells out the consequences, which could include a $1,000 fine, probation, and court appearances. “Landlords faced with this choice will do what the city obviously wants them to do, otherwise they’ll face potential jail time,” Ortiz says.

Though she was evicted after her landlord’s failure to follow the law, Jones believes she was forced out of her home because of discrimination. She argues she was labeled a “problem tenant” simply because her white neighbors had called the police on her so many times. She recalls that a neighbor told her to “go back to where you came from.” The city’s attorneys argue race had nothing to do with her eviction. Yet they also allege that “substantial criminal activity” occurred at her house, including people “smoking pot and doing drugs.” (In 2013, Jones’ son was arrested and accused of breaking into a restaurant and bringing cash registers back to her garage. The charges were dismissed, though he was convicted of a misdemeanor for property damage.) “No one should have to endure the despicable conduct of the Jones family,” they wrote in legal documents responding to the lawsuit, noting that another black family moved into the house after the Joneses. “The fact a black family lives there now and has been welcomed by the community, belies any allegation her family was subjected to any discrimination whatsoever,” they stated.

“It’s similar to the claim of, ‘I can’t be racist because I have black friends,’” Ortiz responds. “They keep saying ‘criminal activity,’ but I don’t hear anything specific,” says Jones, who remembers having a good relationship with her landlord. “I have teenagers—their friends come and go. That does not mean they are selling drugs…Once again, they are stereotyping because I’m black.”

In official descriptions of their crime-free housing policies, most cities point back to Mesa, Arizona, as the birthplace of the program. They usually don’t include much about its architect. In 1992, Tim Zehring was a young police officer in the Phoenix suburb. He was six years into the job and exasperated that he was spending so much time answering calls about noise, suspicious activity, and assaults at apartment complexes. Too often, he thought, landlords called the police when problems arose, but they didn’t do enough to vet their tenants in the first place.

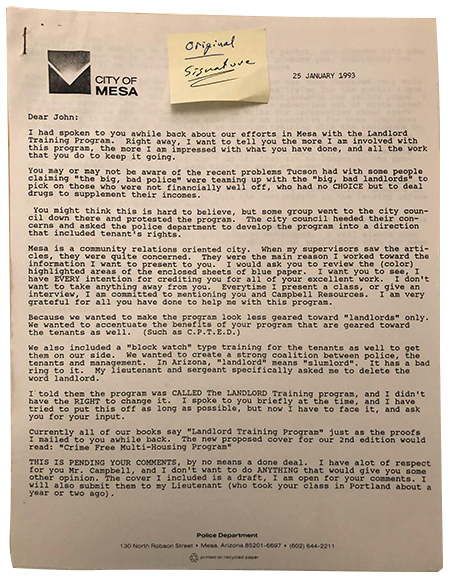

He’d heard about the Landlord Training Program, which had been started in Portland by a man named John Campbell, who was worried about drug crimes in his neighborhood. The idea was to train landlords to screen tenants, improve the design of their apartments to deter crime, spot warning signs of drug activity, and develop rental agreements that would make it easier to evict someone after they broke the law. The Justice Department offered Campbell funding to take the program national. Zehring reached out to him after learning the Tucson Police Department was experimenting with his program, and Campbell agreed to let the Portland model be adapted. But Zehring wanted to make some changes. Tucson’s version of the program had been criticized for potentially discriminating against low-income people of color. He also worried its title would scare off tenants who viewed the word “landlord” as synonymous with “slumlord.” Zehring made some tweaks and proposed a new name: the Crime Free Multi-Housing Program.

Tim Zehring’s letter to John Campbell (p. 1). View the entire document on DocumentCloud

In the mid-’90s, Campbell visited Mesa and reviewed training materials to see how Zehring had implemented his ideas. What he observed concerned him. During one training, Zehring emphasized that landlords may legally turn down any applicant with a felony conviction. (Zehring says that his teachings follow HUD guidance and that he does not encourage blanket bans on people with criminal records.) Mesa police, Campbell says, “missed the point about focusing on healthy communities and tended to side with the landlords.” As Campbell recalled, “The more I looked at it, the more nervous I got about what it was they were doing. This wasn’t the direction we felt comfortable with. We took steps to ask them to no longer use our materials, period.” (In 1995, Campbell accused the Mesa Police Department of sharing his materials without permission; an attorney for the Mesa department denied any copyright infringement, and Campbell never filed a lawsuit.)

Rather than rely on Campbell’s training documents, Zehring helped Mesa develop its own program. In 2000, he created the International Crime Free Association to promote his model. The group conducts trainings for law enforcement officials, who then train local landlords. Landlords receive workbooks that sometimes describe the threat of crime in loaded terms. “When you think of predators, you might think of the lion,” reads a workbook copyrighted by the Mesa police in 1996. “Lions only hunt when hungry; but criminals are always a danger.” When landlords turn down a rental applicant, it advises, “Plan your words very carefully—discrimination suits are filed when managers say too much!” More recent adaptations of the workbook used in California, Illinois, Missouri, and Tennessee included many of these quotes. (Mesa still uses some of the program’s training materials.)

Zehring is proud of his work. In a recent phone call, when I tried to ask him a question, he told me not to interrupt because “I know what questions you’re going to ask.” He then talked for about 30 minutes straight. At times, he launched into oddly detailed hypothetical scenarios, like the story of an evicted man who called a judge an “idiot,” to which the imaginary judge responded, “Shut up. You’re ignorant!”

“One of the problems in our society is everyone screams, ‘My rights, my rights, I know my rights!’” he said. “Well, I’m gonna tell you, what they don’t know is their responsibilities.” Zehring says he never intended for police to order evictions, and that he envisioned his model as a voluntary program that would teach landlords about their rights and responsibilities. He says he urges towns not to codify his model or punish landlords who don’t comply. And he argues that the Supreme Court already ruled that crime-free housing programs were constitutional in a 2002 case called Department of Housing and Urban Development v. Rucker. Attorneys I spoke with noted that this decision upheld public housing authorities’ use of the one-strike rule, but does not apply to the private rental market.

Campbell continues to train police departments with his own materials, which he describes as “community oriented,” as opposed to putting “police at the top of the pyramid.” He says that while evictions for criminal behavior are sometimes warranted, he tries to teach landlords that mass evictions are unnecessary. “This has really been an exercise in deep breathing for me,” he says of his experience with Zehring. The International Crime Free Association program “is sort of a very warped outcome that we’ve tried to distance ourselves from. And it’s been very hard to watch it happen.”

The legal challenge to Faribault’s rental housing law builds on a 2015 Supreme Court ruling that the Fair Housing Act prohibits not only housing policies enacted with discriminatory intent, but also those that disproportionately harm a particular group of people. In 2016, under the Obama administration, HUD issued a guideline clarifying that crime-free housing ordinances violate the Fair Housing Act “when they have an unjustified discriminatory effect, even when the local government had no intent to discriminate.” Yet the Trump administration recently proposed a policy change that would make it harder to file complaints to HUD about disparate impacts in either public housing or private rentals.

The Faribault lawsuit could significantly affect how cities enforce crime-free housing ordinances. If the laws are found to be discriminatory and are struck down, landlords would no longer be forced to evict certain tenants. But that wouldn’t leave property owners without any recourse. Existing laws usually allow owners to evict renters who engage in criminal behavior on the property. Landlords may also amend leases to prohibit drug use. And the civil courts that handle evictions based on claims of criminal activity have a much lower burden of proof than criminal courts. Ramsey, the former housing attorney, points out that crime-free policies may not deter crime anyway: The drop in police calls caused by the rules, she writes, “could also be a result of a chilling effect…on crime reporting when citizens fear the consequences of eviction.”

The ACLU has been challenging crime-free housing policies around the country. In 2017, Hesperia, California, revised its crime-free housing ordinance after the ACLU argued that it discriminated against people on probation. (“I want them the hell out of my town, and I don’t care where they go,” a city council member had said of people with criminal records, according to court documents.) Savannah, Georgia, suspended its voluntary program in 2018 after the ACLU complained about a requirement that landlords reject anyone with a conviction for a violent felony, two nonviolent felonies, or three misdemeanors. Officials in Painesville, Ohio, amended their program after the ACLU pointed out that its screening for criminal records discriminated against black people. In July, the Washington attorney general’s office filed a lawsuit against the city of Sunnyside, which it said had used its program to evict mainly “Latinos/as, residents with children, and women,” sometimes without court orders.

The Liga Guerrero 2018 champion Somali team plays in the quarter finals of this year’s tournament, winning 4-3 at Faribault Middle School.

Andy Richter

In October, Faribault’s city council granted preliminary approval to amendments to its rental housing law. Under the proposed changes, children younger than two would be exempt from the occupancy limit, and the city would specify that the crime-free housing program does not restrict landlords from renting to people with criminal records. A HUD guidance sheet would also be included in the training manual for landlords. “We are pleased the City of Faribault acknowledges its rental licensing ordinance, as it exists, is problematic and is open to revising it,” said Teresa Nelson, the legal director of the ACLU of Minnesota. “However, none of the changes it is proposing alter the unlawfulness of its ordinance as described in our lawsuit.”

“The city has an obligation under the Fair Housing Act to not discriminate in housing on the basis of, among other traits, race and national origin,” she continued. “It is the city’s failure to meet this obligation—not the landlords—that is driving this lawsuit.”

As the case with her name on it continues, Thelma Jones is still feeling the effects of Faribault’s law. After she was evicted, she found an apartment in another part of town. It’s on the second floor, and climbing the stairs is difficult because she has an inflammatory lung disease. Without a yard, she had to give up the kids’ trampoline and the family’s poodle mix. The new two-bedroom place is too small for all her kids. Her 23-year-old daughter, Priyia Lacey, who was pregnant at the time of the eviction, had to look for somewhere else to live. Lacey struggled to find housing because her background check revealed an old warrant and assault judgment, according to the ACLU lawsuit. Without a room in her mom’s apartment, she had to sleep in friends’ living rooms with her infant son.

Jones doesn’t host parties at home anymore and rarely invites anyone over for dinner, worried about triggering more complaints from her neighbors. “It’s clear they think what they did to me and my family is okay,” she says. “They don’t care how positive you are to the community: I work hard day in and day out in the health care field—I take care of people, probably some of their relatives—and they don’t care.” She thinks every day about packing up and leaving town for good. “Any black person that thinks they want to move to Faribault and gonna make that their home,” she says, “they are making the biggest mistake of their life.”