Carolyn Cole/Getty

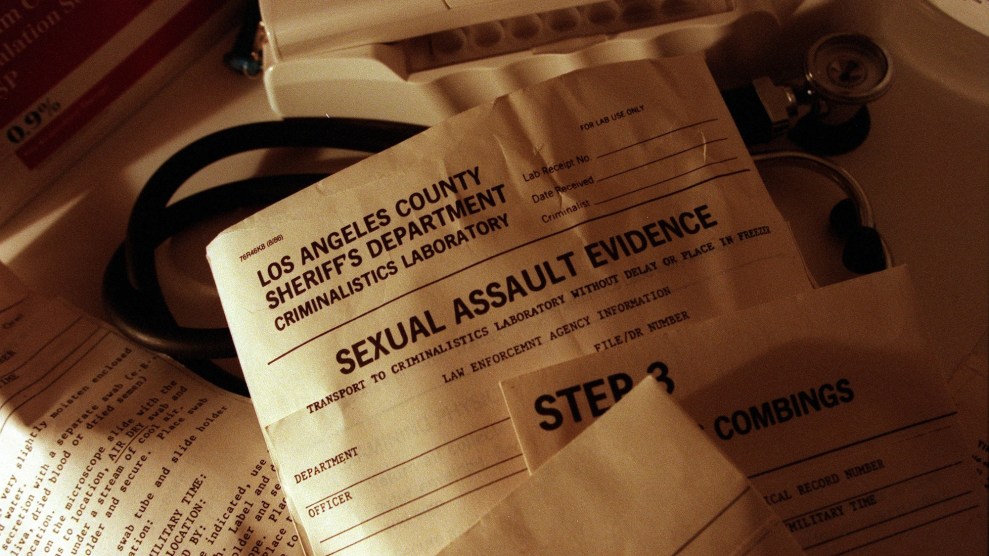

Sometime after 2 a.m. in a dark exam room at the San Francisco General Hospital, a sexual assault nurse examiner turned on a handheld blacklight. Heather Marlowe looked down at her body. Her stomach and thighs were glowing. The nurse took swabs, and reassured her that when police analyzed her rape kit, they would have plenty of DNA to test. Marlowe felt dazed, in a state of shock. “You don’t really process that that was an indication that your life and body were used,” she says. “I just thought, OK, there’s ample saliva, there’s ample semen.”

That was May 2010. A year later, the San Francisco Police Department had yet to analyze the kit; according to court documents, when she pressed them, an officer told her the forensic lab had a “backlog” of more “important crimes.” A year after that, the department said her still-unprocessed rape kit had been put in storage and the case labeled “inactive.” It took until November 2012 for the crime lab to analyze the box of evidence collected by the nurse that night, and though the evidence did not get a hit in the statewide DNA database, the results were never uploaded to the FBI’s national database due to “irregularities.” Marlowe, who believes she was drugged before she was raped by a stranger she met at a city-wide festival, says that today, she has still not received any information about her toxicology or bloodwork. And in the years after her rape, as she continued to pursue her own case and began asking questions about other rape kits languishing in SFPD custody, she learned that she was not alone. In 2014, the department announced results of an audit conducted partially in response to Marlowe’s advocacy, which showed there were hundreds of unprocessed rape kits in its possession.

“There’s no closure, there’s no, ‘Your rape kit has been tested and put in CODIS,’ no nothing,” Marlowe says of her case, nine years on. “I was so desperate that I continued to work with the various city officials and advocates and whatnot who told me, ‘Oh no, just wait a little bit longer. They will get to you.’ I realized in retrospect that I think they were just blowing smoke.”

In 2016, Marlowe filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city, accusing the police department of mishandling sexual assault reports like hers by neglecting to process rape kits, allotting too few resources to sexual violence investigations, and failing to properly train and supervise personnel—all of which, the lawsuit argued, had a “discriminatory impact” on women. Her complaint alleged that the police department’s delay in testing her kit was part of a larger pattern of treating sexual assault with “deliberate indifference.” But her case was dismissed by a federal judge, and an appeal was denied by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. On Monday, the Supreme Court denied a petition to reconsider the ruling.

The decision is a blow to the growing number of survivors across the country who have sued local governments for neglecting or mishandling sexual assault reports. For example, last summer, in Austin, Texas, three women filed a class action lawsuit claiming city and county authorities “disbelieved, dismissed, and denigrated” female sexual assault survivors and failed to pursue investigations, in part by not testing DNA evidence. In Maryland last fall, two former University of Maryland-Baltimore County students alleged that the Baltimore police department “covers up reports and refuses to investigate those it cannot cover up.” And in Memphis, Tennessee, a class action battle has been ongoing since 2013, when three women who survived attacks by the same serial rapist filed a complaint focused on the city’s roughly 15,000 untested rape kits. Other cases have been filed in Connecticut, Illinois, and New York.

As awareness about untested rape kits has increased, questions about how to hold police departments accountable for failing sexual assault survivors have lingered. The wave of lawsuits filed in the last few years, mostly in federal court, are an attempt to force police departments to complete the investigative steps they should have been taking all along. They argue that local governments are violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause by under-policing sexual assault, a crime that disproportionately affects women. In doing so, they apply old ideas about the meaning of “equal protection”—stemming from Reconstruction-era concerns about unpunished white violence against black citizens—to modern-day concerns about how the criminal justice system handles sexual violence, according to Deborah Tuerkheimer, a law professor at Northwestern University. “The rape kit issue is really the most visible, most tangible, most easy-to-get-our-hands-around manifestation of a much deeper, more pervasive, more systemic issue,” Tuerkheimer says.

What we think of as the national “rape kit backlog” actually consists of two sets of kits. The first is in crime labs, which maintain an enormous queue of unprocessed DNA evidence—about 169,000 requests at last count, including an unknown number of rape kits. The second group consists of those the police never submitted for analysis. “These kits never even made it to the labs,” says Marlowe, who argues that “backlog” in this case is a euphemism for police neglect. “They’re being stockpiled and never even attempted to be tested.” Over the last decade, city-by-city investigations and audits have revealed warehouses, closets, and lockers full of such unprocessed kits, some of them literally growing mold, and many of them placed there after detectives decided a sexual assault report was not worth investigating, according to the Government Accountability Office. The true number of these unprocessed kits is unknown, but some sexual assault advocacy organizations, including the Joyful Heart Foundation and RAINN, estimate that it reaches into the hundreds of thousands.

Even with the Supreme Court’s denial on Monday, it’s still too soon to tell how successful the other lawsuits will be in court, Tuerkheimer warns. But it’s clear they face an uphill battle. For one thing, when domestic violence survivors tried to make a similar argument about Equal Protection in the 1970s and 80s, the courts required that they show evidence that police officers were intentionally discriminating against women, a high bar. Marlowe’s lawsuit clears that hurdle: According to her complaint, a San Francisco police officer told her that because she was “a woman” who “weighs less than men” and has “menstruations,” she “should not have been out partying with the rest of the city on the day she was drugged, kidnapped, and forcibly raped.” (John Coté, a spokesperson for the San Francisco city attorney’s office, maintains that city employees were “always respectful of her concerns and tried to help.”) But not all cases are as clear cut.

Then there’s a second problem. The Equal Protection clause requires that the government not deny people protection under its laws, but Marlowe’s case begs the question: protection equal to whom? It’s unclear which cases to compare Marlowe’s to. “Are women being discriminated against compared to domestic violence victims who are men?” Tuerkheimer asks. “Or should you be comparing domestic violence to other kinds of crimes?” This problem is part of the reason a judge for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California rejected Marlowe’s lawsuit in 2017, writing that she did not “allege any facts to support a finding that persons who reported other types of crimes were treated more favorably.” Marlowe’s lawyer, Becky James, admits that “there really isn’t a comparable group. There are no other crimes where you have a rape kit. It kind of sets up an impossible burden.”

Then there are the technical difficulties, such as statutes of limitations, which limit the amount of time survivors have to bring legal claims. Marlowe didn’t find out that San Francisco had a stockpile of untested rape kits until 2014, and she sued the city for discrimination within the two-year window provided in this type of lawsuit. But the district court ruled that the statute of limitations clock had actually started running in 2012, around the time her rape kit was finally tested, and that Marlow had filed her legal claim too late. She isn’t the only one stuck in this catch-22: A case in Houston has run into similar problems.

Despite these difficulties, at least one of the rape kit lawsuits has been settled. According to the New York Times, last fall, the Village of Robbins, Illinois, paid an unknown settlement to the plaintiff of an equal protection lawsuit that claimed village police had a “decades-long policy of not investigating rapes against women and girls.”

But if most of the Equal Protection suits end up failing in the courts, there are other ways to hold the cops accountable. In another Chicago suburb, county authorities stepped in and took over local sexual assault investigations after discovering untested rape kits in a 2007 raid of the police department. The federal government has a role to play, too. A Department of Justice investigation into police, prosecutors, and public university officials in Missoula, Montana, found evidence that all three were violating the Equal Protection Clause by failing to respond adequately to sexual assault, and they signed legal agreements to change their practices. But since President Donald Trump took office, the Justice Department has not continued to exert the same kind of pressure on local agencies to do better.

In the meantime, Marlowe is continuing her activism. In 2015, she and one of the survivors suing Memphis formed a nonprofit, People for the Enforcement of Rape Laws, to focus on pressuring police to change how they respond to sexual violence. Meanwhile, her case continues to reverberate in local San Francisco politics: Suzy Loftus, the former president of the San Francisco Police Commission who is currently running for San Francisco district attorney, was accused in Marlowe’s lawsuit of “creating and perpetuating” a policy in the police department of not “promptly and equitably” investigating rape cases. (On Friday, in a controversial move, San Francisco mayor London Breed appointed Loftus interim DA ahead of the election.) In a statement, Loftus campaign spokesperson Debbie Mesloh said that “after listening to the voices of sexual assault survivors,” Loftus helped clear San Francisco’s rape kit backlog and hold the police department accountable for future delays in testing. Marlowe’s lawsuit, she said, was “meritless.” If elected, Loftus has vowed to review previously declined sexual assault cases for potential prosecution, improve police training, and increase services for survivors.

Marlowe doesn’t trust her promises. “It’s all talk about survivors, survivors’ voices and survivors’ stories, victims’ rights,” she says, “until somebody sues.”