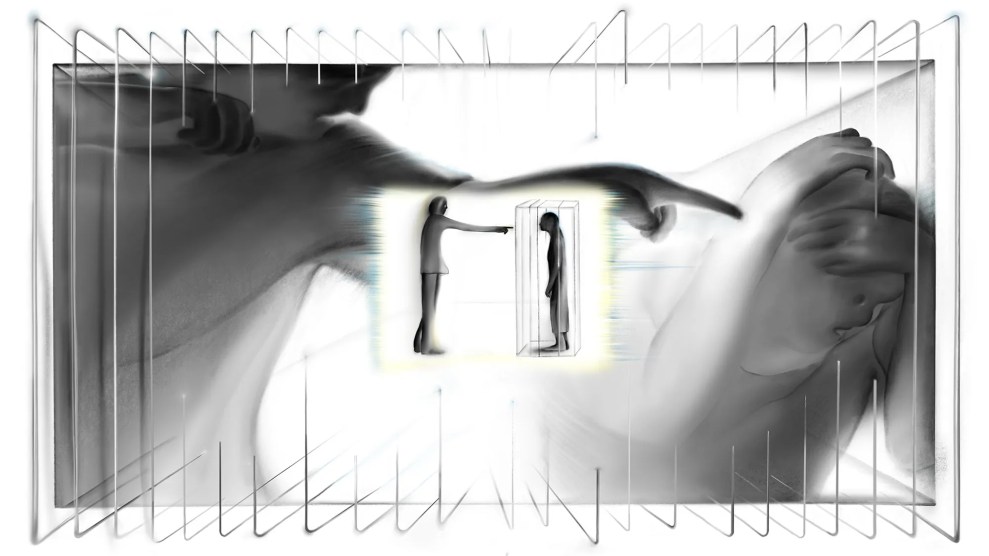

Tents for treating COVID-19 patients at San Quentin prisonJustin Sullivan/Getty

Up to 8,000 incarcerated people across California will be released by the end of August in response to the COVID-19 crisis in the state’s prison system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said on Friday.

The newest release plan—announced as corrections officials struggle to cope with an explosive and deadly outbreak at San Quentin State Prison in the San Francisco Bay Area—targets some of the most vulnerable prisoners and institutions in the state’s overcrowded, 112,500-person prison system. Officials said Friday they will now consider releasing people with less than 365 days left on their sentences from San Quentin and seven other prisons with high numbers of sick, older, or medically vulnerable inmates. People from across the prison system who are at heightened medical risk for COVID-19 due to age or an underlying medical condition will also be eligible for release, so long as they are considered a “low risk” for violence and are not serving life-without-parole or death sentences. And CDCR Secretary Ralph Diaz announced on Thursday that nearly all prisoners’ sentences will be reduced by 12 weeks. All prisoners will be tested for COVID-19 within seven days of release, according to CDCR.

“These steps represent great progress,” says Stefano Bertozzi, the former dean of the University of California, Berkeley’s public health school, who last month coauthored a memo raising alarms about the outbreak at San Quentin and calling for large-scale releases. “The critical issue now is how quickly it can be implemented.”

In prisons, health care is limited, sanitation is poor, and social distancing is often impossible. A paper released Wednesday in JAMA found that the COVID-19 case rate for prisoners was 5.5 times higher than in the general population; prisoners who got sick were three times more likely to die.

In April, California released about 3,500 people who had less than 60 days as long as they were serving time for nonviolent offenses and were not considered a “high risk” to the community. State corrections officials had announced in June that early releases would be extended to another 3,500 prisoners with 180 days left on their sentences starting this month. But those eligible prisoners tend to “skew young and are not necessarily the inmates with the lowest risk of violence upon release,” Bertozzi says.

“In a place like San Quentin, the platform is already burning,” Bertozzi says. In the other seven targeted prisons—including the California Health Care Facility, California Medical Facility, and Central California Women’s Facility, which house the state’s oldest and sickest prisoners—the situation could be “out-of-control tomorrow,” Bertozzi says. “CDCR needs to prioritize those releases and to move as quickly as possible.”

While James King, an anti-incarceration activist with the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, called the plan a “step in the right direction,” he added that further releases would be necessary to allow for physical distancing inside prisons.

That includes at San Quentin. On Monday, Gov. Newsom said state officials plan to reduce the population to 3,082 people, or exactly 100 percent of its capacity (the prison has been operating with hundreds of excess prisoners for years). But that might not be enough. Last month, Bertozzi and other public health experts called for San Quentin’s population to be cut by 50 percent. “I strongly believe that 100 percent capacity is far too condensed and confined to keep people safe,” says King, who was released from San Quentin in December. “It needs to be half of that.”

It’s still unclear how many prisoners will qualify as both “high risk” for COVID-19 and eligible for release. Newsom has previously said that 42 percent of California prisoners are at heightened medical risk for the coronavirus, or nearly 50,000 people. CDCR says its officials will now consider people over the age of 65 who have chronic conditions, and those with respiratory illnesses like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which may not capture the full swath of people vulnerable to the coronavirus, according to Bartozzi. “It’s just so discretionary,” Alison Hardy, an attorney for the Prison Law Office, says.

Additionally, all prisoners will receive a 12-week credit on their sentences “to recognize the immense burden incarcerated people have shouldered through these unprecedented times” CDCR said in its press release. Sick or vulnerable prisoners have been isolated, sometimes in solitary confinement, while whole prisons have been locked down, with programs and visitation canceled. “While this will in no way make up for the multitude of changes and impacts to your lives this pandemic has necessitated, I hope it will play a part in recognizing your sacrifice and the role you continue to play in keeping the institutions safe and peaceful, which enables staff to focus on providing care to those who are ill,” Diaz wrote in a letter to incarcerated people on Thursday.

On Monday, state officials are expected to brief a federal judge on how much space is available for quarantines and COVID-19 treatment in each state prison, according to Hardy; until then, she says, it’s difficult to tell just how much of an impact the 8,000 expected releases by August will make. “Definitely, we’re moving in the right direction,” Hardy says. “If they’re estimating 8,000 people, I hope that that’s enough to respond to emergencies like San Quentin.”