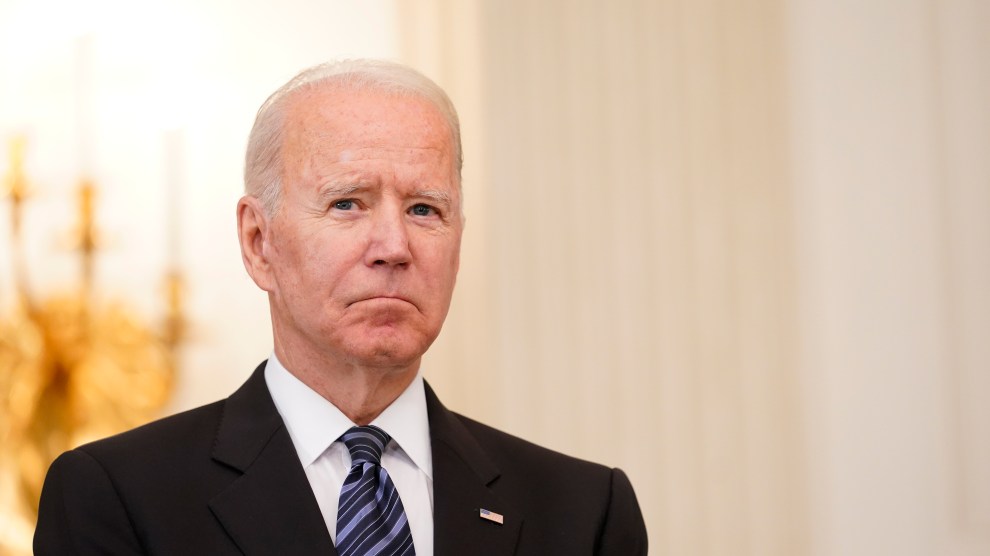

John Minchillo/AP

Late last year, there was a robbery on my block. I was curious about how the police described the incident, because if early reports were to be believed, I was outside that evening while my neighbor’s home was being burglarized. So, I went to my local police department’s Twitter account to check, only to discover that, indeed, I was outside at the time of the robbery. Soon, I was mesmerized by the seemingly endless stream of tweets recounting robberies, assaults, and car jackings. I hastily exited the screen—just a glimpse of the feed full of crime made me feel as if danger was everywhere. Maybe the next time I left the house, I too would become a victim.

Of course, the rational part of my brain knows that, statistically speaking, because of my socioeconomic status, it’s unlikely that I’ll be the victim of a crime, especially a violent one. But that fleeting moment of paranoia while browsing Twitter was a vivid example of the apparently unbreakable connection between our experiences of policing and crime.

Conservative politicians, media figures, and public officials are all explaining what they consider to be spikes in crime and increasing homicide rates as the inevitable consequence of the defund the police movement. After video of white police officer Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man in Minneapolis, went viral last summer, the largest racial justice demonstrations in a generation spread across the country and police reform once again dominated the national conversation. This time it focused on a proposal known as defunding the police, which left-wing activists have championed for decades. The policy targets removing resources from law enforcement and using them where they’re needed, for education programs, for instance, and social services. But over the last year, homicide rates began to rise. And conservative politicians and law enforcement officials, hypnotized by their own versions of a police Twitter account, seized the opportunity to create a new panic rooted in a false causality: Defunding the police, they argue, has caused a surge in crime.

This graphic demonstrates just how wrong & dangerous efforts to defund the police are. Democrat-run cities across the country who cut funding for police have seen increases in crime. This #NationalPoliceWeek please join me in standing up to defend our brave men & women in blue. pic.twitter.com/TROQgn59TP

— Patrick McHenry (@PatrickMcHenry) May 13, 2021

First things first: Is there really a surge in crime? It is true that homicide rates are rising in some cities across the country, but it’s not as simple as the fear-mongering we’re hearing from the right. “It’s hard to give a nice simple overview of what crime is doing,” Charis Kubrin, a professor of criminology at University of California, Irvine, says. “Crime was rising drastically in the 1980s through the early 1990s, then we experienced the crime drop. Now it seems to depend on which city.”

In fact, Americans always seem to be convinced that crime is rising. “It’s an entrenched, salient perception,” Kubrin explains. In 20 of 24 Gallup polls conducted between 1993 and 2020, at least 60 percent of Americans have said crime is going up nationally, despite the data showing a general downward trend of violent and property crime during most of that period.

Complicating matters further is the way crime statistics are collected. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Bureau of Justice Statistics are the main federal agencies that collect data about crime trends. But their reports are often incomplete, don’t include every type of crime, and aren’t available until well after the calendar year is over. When those statistics do appear, they aren’t sufficiently detailed to paint a full picture. For example, the entire state of California may be experiencing low levels of crime, but once researchers drill down, cities and even specific neighborhoods may be experiencing the reverse. Which is to say, there are no neat narratives about even the existence of an epidemic of wrongdoing.

The more pressing question is whether crime rates and police budgets are even related? If cities shift resources from police officers to, say, mental health services, will homicide rates spike? “There is no national evidence of that,” Ronald Wright, a professor of criminal law at Wake Forest University says. “What we have is anecdotes.” Moreover, even though defunding the police has gained currency in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, it’s not as if local police departments have been stripped of all their resources. “While lots of people have talked about defunding the police, hardly anyone has done it,” Wright says. “And in the cities that have done it, there’s no correlation with [rising crime rates].”

If defunded police forces all over the country haven’t led to more homicides, what has? “We’ve just been through this massive disruption,” Wright says, referring to the seismic effects of the coronavirus pandemic. Last year, my colleagues Madison Pauly and Julia Lurie reported on the alarming rise of domestic violence 911 calls during stay-at-home orders. For example, Seattle, one of the first major cities to be shut down by COVID, received 22 percent more domestic abuse phone calls in the first two weeks of March 2020 than during the same period the previous year.

Add to that, skyrocketing numbers of new gun sales. In 2020 and in 2021, gun sales broke records, many of them from among first-time owners, not just the usual gun aficionados adding to their collections. “My gun store has had a run like I’ve never seen before,” Todd Cotta, the owner of a California gun shop told NPR in April. “It was just an avalanche of new gun buyers for the first time.”

What many of those who conflate defunding the police with rising crime rates miss is how wrong, even dangerous, glib causalities about crime are. It’s too simple to say that crime is on the rise because of X. But one thing is clear to the experts. “National crime policy is usually where we overreact and do more harm than good,” Wright explains. “The times we reduce crime is when local officials know what they need for their communities.” Kubrin notes that it’s much too early to tell what’s causing the spike in murders, but it’s unlikely that there’s a single reason. “Crime is multidimensional,” she says, pointing to a variety of factors such as “gangs, drug policies, socio-economic factors, and police community relations” that exist in various measures in different communities.

The defund-the-police correlation to crime implicitly connects Black Lives Matter protesters and other activists to the problem. But we’ve been here before. Back in 2014, white police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, a Black 18-year-old in Ferguson, Missouri. His death and a grand jury’s decision to not indict Wilson sparked weeks of violent unrest in Missouri and across the country. In the aftermath of the protests (and in the wake of other high-profile police shootings that led to mass demonstrations), violent crime began to rise. Some theorized that it was the “Ferguson effect”, which posits that agitating against the police would result in a retreat by law enforcement from communities, thereby freeing criminals to wreak havoc.

In 2019, crime researchers Richard Rosenfeld at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and Joel Wallman at the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation took a hard look at the data and found that there was no Ferguson effect. The authors studied 53 large cities and their arrest and homicide rates between 2010 and 2015. “We find no evidence of an effect of arrest rates on city homicide rates for any offense category for any year in this period, including 2015, the year of the spike in homicide levels,” they wrote in their study, “Did de-policing cause the increase in homicide rates?” which was published in the journal Criminology & Public Policy.

Part of what makes the conversation about crime rates and police budgets frustrating for experts is that in the same way, it’s impossible to demonstrate that defunding the police exacerbates crime, the reverse is also true: We don’t have much evidence indicating that hiring more police officers or giving them more resources will reduce crime. “When crime goes up, the first reaction is we need more cops, more money, more resources,” says Kubrin. “But there is not a linear relationship, simply add more cops and stir is not a solution that works across the board.” She stresses that it’s the quality not the quantity of police officers that can make a difference in communities.

But no matter how much evidence, or lack thereof, exists for the protests causing a crime wave, the narrative very easily has taken hold. And that’s for a very specific reason. Local media plays an outsized role in keeping people in a constant state of fear about being victimized, even if the chances are slim. Turn on any evening news program—or I would add to that your local police department’s Twitter feed— and it can feel as if nothing else happened that day but horrible crimes. According to Kubrin, there’s a direct correlation between local news consumption and fear of crime. In turn, politicians and other prominent figures play on this perpetual fear-cycle by singling out whichever boogeyman to blame. One year it’s the “Ferguson effect.” This year, as Fox News TV host Tucker Carlson said on his show in March, it’s the conviction that “when you defund the police, people die.”

For me, the time I spent looking up the police tweet about a local robbery only to end up feeling as if car jackings were happening on every street corner was brief. But for the millions of people who are listening to officials claiming that because police have been defunded violent crime is coming soon to a neighborhood near you, the damage will be long lasting. If the fear mongers are successful, many Americans will trade progress on policing and racial equality for a false sense of security. And that very well may be their intention.