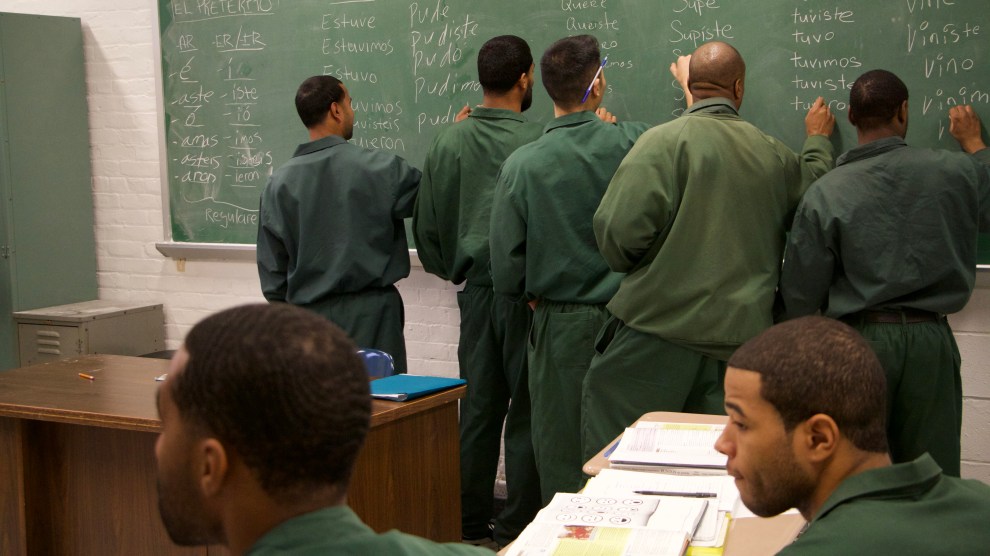

Jerome “JJ” Taylor needed just one more humanities credit to earn his bachelor’s degree from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri—the college he’d dreamed of attending since he was “running the streets” of the city a decade earlier. But in early 2020, before the 30-year-old could finish his final class inside the Eastern Missouri Correctional Center, where he was enrolled in the university’s Prison Education Project, the pandemic lockdown slammed into place, preventing professors from entering the facility.

Faced with the prospect of canceling the semester altogether, the Prison Education Project went digital using the students’ prison-issued electronic tablets. The 7-inch tablets, from a private company called JPay, were loaded with an educational app that allowed students to access coursework, submit assignments, and communicate with their professors. JPay’s system was free to students and the college, but the technology was unreliable, according to Taylor and his professor, Barbara Baumgartner, who is also the project’s associate director. Documents couldn’t be accessed, messages weren’t received, and recorded lectures couldn’t be longer than a few minutes. The JPay kiosks Taylor needed to upload his schoolwork were often down. When his own tablet broke, he cajoled a prison officer to make copies of his writing assignments and borrowed others’ tablets to communicate with Baumgartner.

“For one credit, I absolutely did everything I had to do,” Taylor says. When he finished the class, allowing him to graduate before his release date, it was as much despite the JPay system as because of it. Taylor was one of the lucky ones. “We had some really excellent students who ended up withdrawing from classes or not doing so well,” Baumgartner says, “because it was so hard for them to keep their motivation level up, to not be demoralized, struggling with the various kinds of technological difficulties.”

JPay, a subsidiary of Aventiv Technologies, had provided the tablets at no cost to the Missouri Department of Corrections. But they were never really free. In fact, selling the content used on these tablets is big business for JPay. People in the Missouri state prison system have to pay JPay for almost all noneducational content, including 25 cents to send an email and up to $55 to listen to a single album. When the company started rolling out tablets in New York prisons in 2018, it reportedly projected that purchases on the devices over the next five years would amount to $8.8 million.

Tablet-based education, like the college class Taylor took, was long the exception to what JPay would charge for. Instead, the company’s educational platform, Lantern, served as a selling point in securing state contracts, allowing JPay to spin its presence in prisons as a forward-thinking reform effort. “Education is the key to reducing recidivism,” said then–JPay CEO Ryan Shapiro in a press release announcing Lantern’s launch, adding that his technology would have far a greater impact than other prison education programs.

WashU had used Lantern since 2019 to supplement its in-person classes. In the first year of the pandemic, its program became wholly reliant on the app. Then, in late 2021, despite all the technological issues, JPay told WashU that it would have to start paying to keep using Lantern. At least one other university using the app was recently given the same warning.

What changed? Certainly, the pandemic-induced demand for remote learning created new opportunities for the company. But there’s also a big pile of cash Aventiv appears to be eyeing: a federal ban on Pell Grant aid for prisoners that will lift next year, making millions of dollars available for incarcerated people looking for a college education.

In fact, Aventiv’s subsidiaries, which include the prison telecom giant Securus, have a long history of profiting off the captive market of prisoners and their families, most famously by charging some incarcerated people $25 for a 15 minute phone call. (Amid public backlash, the company lowered its top rates. Aventiv spokeswoman Jade Trombetta says that aside from international calls, no calls on the Securus network cost more than 21 cents per minute; according to research by the Prison Policy Initiative, as of June 2021, it charged up to 25 cents per minute.)

Now, some critics worry that as financial aid becomes more widely available to prisoners, Aventiv will try to “own that market” on prison education, as Bianca Tylek, founder and executive director of the anti-prison industry group Worth Rises puts it. Could Aventiv leverage the growing ubiquity of its tablets and existing relationships with state corrections departments to make deals with schools? “Nobody said, ‘We don’t want tech in prison,’” Tylek says. “But the reality is we should not be depending on the same companies that have preyed on our communities and people for decades to be the ones to introduce that technology.”

JPay’s business relies on fees—from the service fees it collects each time someone transfers money to a prisoner online or by phone, to the extra charges it imposes on some probationers and parolees when they make required state payments for the cost of being supervised. Until last year, when it was fined by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the company charged former prisoners unavoidable fees simply to access the money they were owed upon release.

Meanwhile, JPay’s sister company, Securus, has for years faced ethical and legal questions about its business practices. In both Missouri and California, Securus has settled lawsuits alleging it illegally recorded attorney-client communication. In 2018, Sen. Ron Wyden asked the FCC to investigate a tracking service Securus sold to law enforcement that could locate almost any cellphone in the United States. And as Mother Jones previously reported, Securus offers remote video calling systems to prisons and jails—theoretically making it easier for incarcerated people to see loved ones—but used to include a contractual obligation that facilities eliminate in-person visitation so that families were wholly reliant on its services. (The company says it removed that language from its contracts in 2015.)

In 2019, amid public scrutiny and activist pushback, Securus and JPay’s private-equity owner—Platinum Equity, run by Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores—created Aventiv Technologies, a parent company that would serve to give his controversial enterprises a new face. And he announced a “transformation agenda” to make Aventiv socially responsible and affordable to its consumers—a group that is disproportionately Black and Latinx, low-income, and often from historically underresourced communities. “Aventiv is an innovator transforming the use of technology to benefit the incarcerated and their families, friends, and communities,” Trombetta says of the company’s work in this arena. “We are part of the solution to a difficult problem, and we’re candid about the fact that years ago, this company was part of the problem, too.” Recently, Aventiv has been looking to go public: As of this fall, the company was in talks to merge with Atlantic Street Acquisition Corp., a SPAC managed by the investment firm MC Credit Partners.

Education programs are a part of the company’s new image. Last year, Aventiv pledged to increase college registration among incarcerated people by inviting community colleges and “minority-serving institutions” to join its platforms. In an email to one potential partner organization last fall, an Aventiv employee wrote that the company would be launching a “broad education initiative” in 2022, including hiring an education department leader and taking steps to increase the “number and quality” of education options available to prisoners.

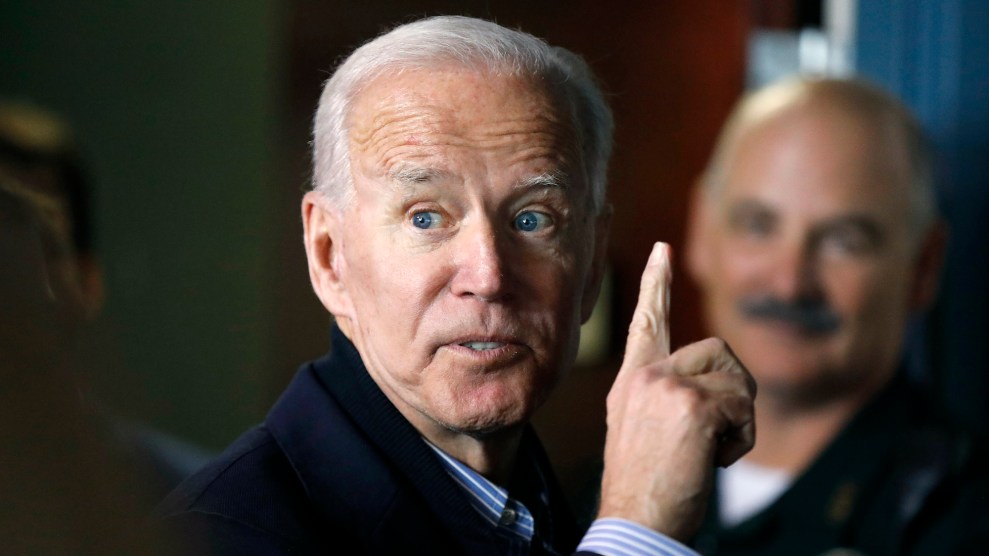

At the same time, a major federal policy will soon give Aventiv more opportunities to cash in on prison-education programs—that is, if it starts charging for its services. In December 2020, Congress voted to end the ban on Pell Grants—the federal financial aid program available to low-income college students—for incarcerated people. The ban has been in place since 1994, when it was passed as part of then-Sen. Joe Biden’s infamous crime bill. The year after the ban, the number of incarcerated people enrolled in higher education programs fell by an estimated 44 percent. Whereas 772 schools offered college programs to prisoners in the early ’90s, by 1997, only eight were left.

This change will open up federal financial aid for more than 463,000 incarcerated people who have a high school diploma or GED, according to an estimate by Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. Those who qualify will receive up to $6,495 toward the cost of an undergraduate education—the same as non-incarcerated students. And because incarcerated people earn pennies on the hour, if anything, for prison labor, nearly all meet the Pell income requirements.

With the new flow of money, more colleges are expected to get involved in prison education, according to Margaret diZerega, director of the Vera Institute of Justice’s college in prison project. “With this law change, I think colleges can really plan for the long haul and invest in these programs in the way they would any other satellite campus,” diZerega says.

Aventiv appears eager to tap into that new market. According to two attendees of a November meeting with another prison technology company, the co-presidents of the Atlantic Street Acquisition Corp.—the company in talks to merge with Aventiv—said they saw the end of the Pell Grant ban as a business opportunity. At another meeting, an Aventiv representative outlined the company’s plans to expand its education business. A presentation discussed at the meeting, a copy of which was shared with Mother Jones, describes a plan to offer a tiered system of bronze, silver, and gold-level “education partner packages” to schools looking to start prison education programs. Under the plan, schools that signed onto higher-level packages would be able to enroll students from more correctional systems and have access to more customization and support.

The presentation’s slides also described “opportunities” in Alabama and Arizona, noting that the company’s tablets are already in widespread use in those states and that around a quarter of prisoners there will be eligible for Pell grants. (Trombetta says the company currently does not make money from its tablet-based education offerings. “Simply put, when it comes to education our revenue is well below our costs,” Trombetta says. “We’re making these investments out of our pocket because we believe in the mission.”)

Yet whether Aventiv’s foray into prison education will offer real opportunities for students is another question. At the University of Central Florida, the Florida Prison Education Project switched most of its classes from in-person to Lantern during the pandemic, initially using the platform for free. But last summer, as the program was preparing for the fall semester, UCF canceled all Lantern-based classes after Aventiv abruptly informed the school that it would need to pay to use Lantern for its upcoming classes. “It certainly was not at all what they had explained our arrangement would be,” says Keri Watson, the project’s executive director. During her initial discussions with the company in spring 2020, she explains, Aventiv had offered Lantern for free as part of a “philanthropic mission to help support higher education in prison,” in Watson’s words. When she pushed back on the pending charges, explaining that UCF didn’t collect any money from its incarcerated students, Aventiv dropped its proposed Lantern fees from $250 to $100 per student per semester—still cost-prohibitive for the nearly all-volunteer program. Nearly 230 prisoners in UCF’s program had Lantern classes canceled that fall; without the platform, UCF’s prison program has now scaled back dramatically.

Aventiv also informed WashU late last year that it would need to start paying the $250 per student fee for Lantern each semester once its prison program became “revenue generating”—in other words, once the university’s incarcerated students started receiving Pell Grants, Baumgartner says. Students commonly take 10 semesters to graduate from WashU’s program—meaning Aventiv could ultimately benefit from more than a third of each student’s lifetime Pell assistance, siphoning funding that would otherwise stay with the prison education program. “We don’t want to pass along costs to the people using them inside facilities, and we don’t want to be held back from providing educational assistance to more incarcerated people, so of course we’re looking at equitable ways for schools to share in the costs,” says Trombetta.

“I personally think it’s shameful,” Baumgartner says. “It’s clearly just a way to for JPay to make more money.”

JPay launched Lantern in 2015 after developing it with the help of John Dowdell, then-leader of the correctional program at Ashland University in Ohio. Once a small Christian school $70 million in debt, Ashland became one of the country’s largest prison colleges—operating in 13 states and Washington DC—after the Trump administration approved it in 2016 for a pilot program to restore financial aid to some prisoners.

According to a 2020 investigation by the Marshall Project, the pilot program brought in almost $30 million for the school. Beyond Ohio, Ashland’s program operates almost entirely on tablets or computers, which has allowed it to scale to 120 facilities, according to the university’s website. Classes consist of digital content—recorded lectures, electronic reading assignments, quizzes—which students typically work through alone, never meeting their professors in person. In total, 60 percent of Ashland’s incarcerated students use Lantern to access their courses, says Hugh Howard, Ashland’s media relations and social media manager. According to the Marshall Project, students in Ashland’s program felt little engagement or accountability, and for some, the struggle was for naught: Students in one Georgia halfway house reported having lost credits for classes in progress when they were released from prison and had little way to continue pursuing their degrees once they were out.

Howard characterized these students’ experiences as “rare outliers,” adding that while there may be “occasional and isolated” technical problems with hardware students use to access their classes, “the overall response we have received from students has been overwhelmingly positive.”

Of course, remote learning has become a necessary option during Covid, within prisons and outside of them. Yet even before 2020, prison officials tended to like the Lantern-dependent model because it allowed them to offer college to prisoners without sacrificing security, says Heather Erwin, director of the University of Iowa’s Liberal Arts Beyond Bars program and an expert in prison education technology. On a tablet, there’s no need to screen professors or books entering the prison, no need to set aside space for classrooms and computer labs.

Academic institutions have different priorities—creating access to knowledge, teaching people to think critically about their place in the world—that conflict with prison systems’ focus on control, Erwin says. What’s more, diZerega explains, “If you are in a classroom with a professor, and you’re talking about your ideas, and you’re having discussion and disagreements about your ideas, the skills in the room that you’re developing are ones that you can apply to a lot of different areas of life.”

“Having people come in from the outside, building those relationships, that social capital is also really important,” she adds.

For many educators, working with Aventiv brings its own particular baggage. “I am aware that a lot of people thought we were making a deal with the devil to use JPay,” says Watson from UCF. “I felt that, given the circumstances of the pandemic, something was better than nothing.”

But after three semesters of struggling with the system’s technical issues, she found that 22 percent of her program’s tablet-based students had successfully completed their classes, compared to 90 percent of students in the one art class that met in person.

“When we are forced to teach with Lantern, it is a subpar educational experience,” Baumgartner from WashU says. Five other educators and program directors for college-in-prison programs that used Lantern during the pandemic told me they experienced technical problems with the system that disrupted students’ learning.

Platforms like Lantern may have some benefits post-pandemic—like allowing schools to offer classes in far-flung rural prisons, or supplementing in-person classes with an extra channel for instructors to communicate with students. Yet Jessica Neptune, director of national engagement for the Bard Prison Initiative, an influential college-in-prison program, cautions against the unforeseen consequences of allowing tablets any foothold in prison higher education. “We worry that—particularly when there are profit motivations at play—tablets can act as a trojan horse, moving from supplementing to supplanting in-person college opportunities,” Neptune says. (“Our platform is intended to augment in person classes and never replace them,” Trombetta says. “The reality inside facilities is that education is limited by everything from security to resources.”)

There are some safeguards in place to keep tablet-based, Pell-funded educational programs of dubious quality from taking over the field. For one thing, schools that want to enroll prisoners as more than 25 percent of their student body must currently get a waiver from the Education Department in order to receive Pell money (Ashland holds one such waiver). And there will be more protections to stop low-quality programs from taking advantage of the Pell money, says Bradley Custer, senior policy analyst at the Center for American Progress. By next year, the Education Department is expected to issue regulations that will require prison education programs to maintain approval from the department, college accreditors, and corrections officials using required metrics like student job placement rates and faculty turnover.

Regardless of whether Aventiv succeeds in tapping into Pell Grant money, getting more involved in prison education could have public-image benefits for the beleaguered company. And some critics suspect it could even help with their merger talks. “They clearly have an interest in shedding the negative image that has been portrayed of them through the media—which, to be clear, is an accurate image,” Tylek argues. “This is not their business, but it looks good. People definitely feel better about education, and education in prison.”

One person who won’t buy into Aventiv’s new image: JJ Taylor, who today is out of prison and a student at LaunchCode, a nonprofit that helps people from nontraditional backgrounds pursue careers in tech.

When Taylor thinks about JPay’s influence on his time inside, he thinks not only of his difficult last semester, but of the high fees the company extracted from him and other incarcerated people. Some days, he found himself choosing between paying for music to help power him through his schoolwork and having enough to eat from the prison commissary. Oftentimes, he chose the music, reasoning that it would fuel him for longer than a cup of coffee. “It’s one thing to commit a crime, and do time,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean that you have the right, or that it’s a just cause, for you to suck all of my blood while I’m paying my debt to society.”