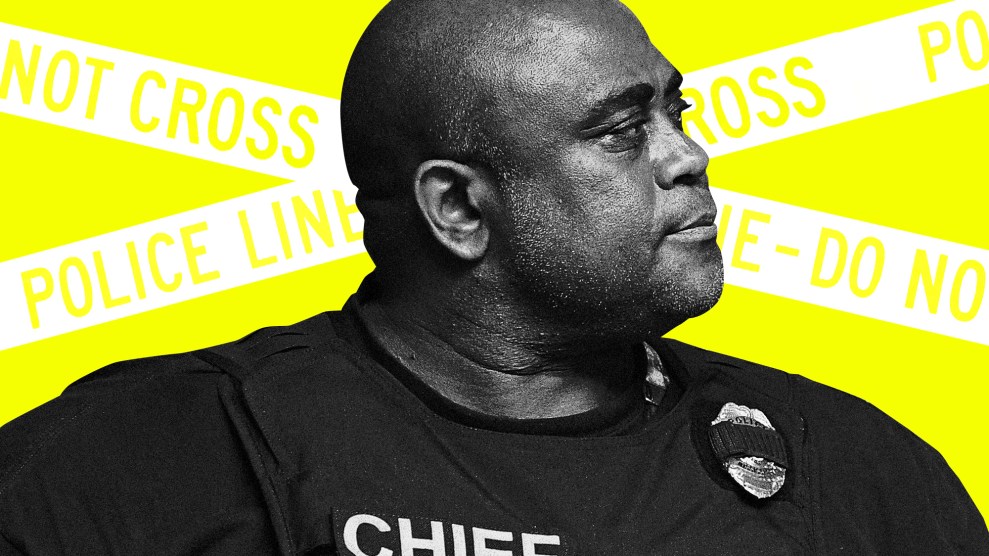

On a muggy evening early in the pandemic, Jervis Middleton, an off-duty police officer in Lexington, Kentucky, sat in his cruiser typing determinedly on his phone. The city was tense. One week earlier, a video of white Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin slowly asphyxiating George Floyd had set off national protests, and Middleton and his fellow officers had been facing crowds of angry demonstrators in the streets for days. The brass had sent out an alert offering overtime to cops willing to work extra shifts.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

They are calling some of our folks in, Middleton typed into Facebook Messenger. I gave them a big fat NO again. He added, sloppily, Im about to monitor our radio traffic. He glanced at the message and hit send. He then flipped on his radio and listened for useful intel. He eavesdropped for only a few minutes, according to later testimony from the department’s 911 administrator, but those few minutes would go a long way toward costing him his job.

Police investigators would later conclude that Middleton was conspiring with the enemy, so to speak. At the other end of those messages—obtained from the city through a public records request, along with a trove of documents related to the department’s investigation of Middleton—was his friend Sarah Williams, a local activist. In making the case for Middleton’s firing, the department’s prosecutors would emphasize his radio monitoring and a handful of his messages that they argued included “departmental” or tactical information. Middleton had shared a screenshot, for example, of the internal notice offering overtime to officers. He mentioned at one point that an emergency response unit was rolling out. Another time, he informed Williams he was driving around (off duty) to see if he could spot any plainclothes officers working the crowds—he didn’t.

More broadly, the exchanges, bits of which are redacted, consist of Middleton saying, sometimes literally, “FTP”—fuck the police. The messages channel his sympathy for the protesters and his pent-up rage over racist policing and casual racism within his own department, some of which he claims targeted him directly. He takes issue with the conduct of certain white officers and commanders and feeds Williams embarrassing information about other officers, encouraging her to goad them with it during the protests. I’m not gonna lie…he messaged her at one point. I got emotional when I rode by and watching it through the night! I circled yall while yall were originally in front of the court house… I tried to find out who was [police emoji] in plain clothes but couldn’t see them.. I saw two cocksuckers up by district court, but couldn’t fully make out who they were… I should have went ahead and stood out there… I probably will Sunday.

As a 13-year veteran on a mostly white force, albeit one led by a Black chief, Middleton grappled with dual, and dueling, loyalties. There was the fraternal code, the thin blue line between order and chaos that police profess to protect. But as a Black man, he’d reached a breaking point. The United States is amid “one of the biggest civil rights movements since the ’60s,” he testified at the February 2021 disciplinary hearing that would result in his termination. If “we don’t say something about stuff now, when will we?” The department’s investigators suggested that cops were welcome to their political opinions, but argued that Middleton’s behavior had crossed the line. The city council followed their recommendation and sent him packing.

Black officers in majority white departments “have to do an identity negotiation where you have to decide, are you blue or are you Black? No one else has to do that,” says Tracie Keesee, a co-founder of the Center for Policing Equity who served as a police captain in Denver and later as the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for equity and inclusion. “When you’re with officers of color, you’ll hear them say, ‘I want to be able to make change from the inside.’”

But speaking out, as Middleton knew, risks being sidelined—or retaliated against. (“You got to go along to get along,” he told me.) So when he felt Black and white officers were being treated differently, he didn’t make too big of a stink—officially, anyway. “I’ve seen it a lot, especially now,” Keesee told me. “You report it and nothing happens. There’s an exhaustion. You’re waiting for a new chief, waiting for an administrative change that never comes.”

May 31, 2020: Protesters march near downtown Lexington to protest the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

Ryan C. Hermens/Lexington Herald-Leader/AP

Lexington, like many American cities, is more racially diverse than its police. Black people make up about 14 percent of the city’s population but only about 9 percent of its sworn officers (50 of 553) as of September. And only 11 Black cops were ranked sergeant or higher.

In the decade prior to Middleton’s firing, citizens made more than 1,000 complaints against Lexington officers. Just 1 in 10 resulted in any formal disciplinary action, and only one cop was fired. (Another officer, who left the department in 2002—and whose supervisor had recommended “strongly” against his reemployment “at any time in the future,” according to a memo obtained by a local paper—was subsequently hired by the Louisville Metro Police Department and participated in the 2020 raid on the home of Breonna Taylor, the Black emergency medical technician whom officers gunned down in her own flat. He was acquitted of reckless endangerment for firing wildly into her neighbors’ apartment, but now faces related federal charges for civil rights offenses.)

Of the 30 racial-bias allegations filed against Lexington officers from 2017 through 2019, 28 were dismissed and none resulted in discipline—not even for Jesse Mascoe, a white officer Middleton name-checked in two of his messages to Williams. According to court documents, Mascoe was the subject of 17 complaints containing a range of allegations—about half related to racial bias, according to Middleton’s lawyer. That’s almost as many as Chauvin racked up before murdering Floyd. In 2019, Mascoe got a 60-day suspension for engaging in a car chase with a vehicle that had excessively tinted windows, resulting in a serious crash that involved civilians. For additional driving violations that “placed members of Lexington roadways at a serious risk of injuries or death,” Middleton’s lawsuit notes, Mascoe received only a written reprimand and a two-week suspension of take-home privileges for his police vehicle.

Middleton contends that his firing is emblematic of the unequal treatment Black officers face within the ranks, and that his termination was partly a response to his pushback against racism in the workplace. Soon after his dismissal, he filed a discrimination lawsuit against the city demanding reinstatement, monetary damages including back pay, and legal fees. The goal of the department’s disciplinary process is typically “rehabilitation, rather than termination,” the lawsuit contends. “This system, however, only applies to White Officers.” (The Lexington Police Department, citing the litigation, declined to answer questions for this story.)

On November 28, a federal judge issued a summary judgement in favor of the police department, but Middleton’s lawyer, Sam Aguiar, says he has already filed paperwork signaling his client’s intent to appeal. “We think the judge’s ruling erred on a few different important issues, and that the errors are reversible. And we just hope that the court of appeals feels the same,” Aguiar said in an email.

Regardless of the final outcome, Middleton’s policing experiences, his rebellion, and his dismissal provide a rare window into the state of a profession that has struggled with racism and cultural entrenchment. Criminal justice researchers point to a crisis of legitimacy in which some minority communities have come to view police as more enemy than protector. Public outrage over unjust killings, particularly since George Floyd, has pushed that crisis across the thin blue line, prompting some Black officers to seek changes in how their departments operate. But not everyone is willing to go as far as Middleton, whose ongoing legal battle touches on the marginalization of minority police, many of who still feel compelled to suffer discrimination in silence.

“The accusation and the firing are totally unjustified,” says Gary Potter, a professor emeritus at the School of Justice Studies at Eastern Kentucky University who specializes in the history of policing. “The basic fact that Middleton supplied information to people who were organizing protests against the police is true. But that is misleading. He didn’t supply, as far as I know…anything that was privileged, anything that was tactical. He was merely warning them about situations where they might run into conflict with the police. So I would argue he’s doing a service.”

Potter compares Middleton to Frank Serpico, a cop who was retaliated against for exposing wrongdoing within the NYPD—and was later immortalized in a 1973 film starring Al Pacino. “As we know, going outside the department can have severe consequences,” Potter says. “There’s a fairly detailed record of police officers testifying against their own being dealt with in a negative way, both in terms of their departments and by fellow officers. Most end up leaving.”

Aguiar is under no illusion that Middleton’s lawsuit could force the Lexington police to change their culture, but he figured a financial hit might at least result in some soul-searching. “If you don’t stand up against what’s wrong,” he says, “then the status quo will prevail. And we all know that the status quo as it relates to police misconduct and systemic racism is not what our country stands for.”

Middleton was born and raised in Lexington, where he lives today with his wife, former local TV news anchor Kristi Middleton, and their twin teen boys. He attended the University of Louisville, joined a fraternity, majored in biology and chemistry, and graduated hoping to do good in the world. “I didn’t grow up wanting to be a police officer. That was the furthest thing on my radar,” says Middleton, who sports a mustache and keeps his head shaved. He kicks back on his bed during our lengthy Zoom interview, clapping his hands together periodically to emphasize this point or that.

After college, he worked with the Red Cross on the Gulf Coast to distribute aid in the wake of storms, including Hurricane Katrina. In the process, he had friendly interactions with police officers and, through a fraternity brother who was an FBI recruiter, began to explore a career with the bureau. But Lexington’s then-chief, a distant cousin (as is Sarah Williams), swooped in and urged him to consider becoming a hometown cop instead. “It was a calling from there,” Middleton says.

Middleton had been lucky enough to avoid the tense encounters his Black friends experienced with law enforcement—there was one traffic stop he suspected was racial profiling, but the white cop treated him well enough. In any case, he figured he would “try to be part of the solution,” he says. “Now that I’m in there, if I see something, I can say something.” Some friends kept their distance once they learned he planned to be a cop, but Middleton wasn’t deterred: “Most people who know me know that once I make up my mind about something, I’m going to do it.”

He made it through the academy okay, but working in the field had a different vibe—less idealistic. And being a Black cop, he quickly discovered, had unique challenges. “You almost have to assimilate and prove yourself to [white colleagues]: ‘Show us that you are part of our team.’” To make a difference, Middleton would need to make rank: “My primary goal was to advance, move up the chain, get in administration so I could effect change.”

He was more qualified for leadership than your typical beat cop. Many departments, including Lexington’s, require only a high school diploma, and train their recruits at police-run academies. In addition to the undergraduate science degrees, Middleton earned an associate degree in law enforcement and a master’s in criminal justice policy administration. He joined the police union and lobbied on its behalf, and even became a public information officer for the department. But he found it hard to hold his tongue in the face of racist comments. During one training session cited in the lawsuit, a white sergeant barked at him, in the presence of other cops, “Turn your Black-ass face around!” Middleton was “incensed,” he recalls, but when he told the officer’s supervisor about it, “he laughed! Laughed and did nothing about it.” Later, at a union gathering, a white officer whom Middleton had considered a friend called him “token boy,” and went on to use that racial dig on multiple occasions, Middleton testified, even after he let the cop know that he found the term offensive.

When he objected to such comments, “I was labeled as a militant,” Middleton told me. “How can I be a militant? I’m not in here arguing with anybody. I’m just speaking on things that aren’t right.” He witnessed other nonwhite cops, and female cops, targeted for disparaging comments as well. But nobody wanted to talk about it: It’s “that blue wall of silence,” he says.

As if being a minority cop weren’t stressful enough, now he was gaining a reputation as a troublemaker, which he felt made it harder to advance. Over 13 years, despite throwing himself into his career, he never made it past sergeant. Not that he was entirely without fault. On August 6, 2018, a woman filed for a protective order against Middleton, claiming he’d been stalking her since she had put the brakes on their roughly yearlong extramarital affair. Her court petition stated that Middleton “admitted to driving by my house multiple times,” had taken and gone through her cellphone without consent, and had shown up to places she’d gone—though he never approached her. She questioned Middleton about his behavior and expressed her concerns, she wrote, and “about two weeks ago, I cut things off for good.” She was granted a temporary order. The department put Middleton on administrative leave while it investigated, and “transitioned” him out of his spokesperson role.

In court later, the woman, who is white, testified she never feared Middleton, at least until one evening when, while entertaining a friend, her guest spotted someone on her roof she suspected was Middleton, spying on them. A Lexington lieutenant testified that Middleton had asked fellow officers to run a license plate check on the man’s car, and that the department was citing him for second-degree misconduct for improper use of police resources.

In the end, the judge ruled that the woman lacked sufficient evidence for a permanent protective order, and Middleton, who wanted to put the whole mess behind him, cut a deal: He accepted a demotion from sergeant to patrol officer and dropped a due-process grievance the union had filed on his behalf. In exchange, the department threw out the misconduct charge. (Part of the court judgment against Middleton hinges on the department’s claim that he also waived his right to sue over alleged acts of discrimination that occurred prior to the date of the deal.)

Middleton says he regrets having an affair, but he disputes aspects of the woman’s story, including that he showed up places where she’d been. He also contends he was disciplined far more harshly than warranted, especially given how the department dealt with cops like Mascoe—a point he raised in a text to Williams: Cut them deep,he wrote, referring to the officers working the Floyd protests that evening. [T]ell them they’re never mad when mascoe violates black peoples rights or when Officers send dick picks on duty.. but when Middleton fucked a white girl, yall went crazy!

Indeed, Aguiar cites evidence suggesting that his client was demoted, in part, based on the kind of private behavior the department, in other situations, has dismissed as “in the family.” Police records and depositions in the case revealed, for instance, the sordid tale of a white Lexington cop who aggressively stalked a fellow officer he’d been involved with. He would call her incessantly, come to her home uninvited, and at one point allegedly recorded her through her window having sex with another cop and then tried to blackmail her, according to a police memorandum. (The officer denies recording her.) She tried to obtain a protective order against the offending officer, who disparaged her throughout the department as a “whore.” It was a “total shitshow,” Aguiar says—and “they throw out the inquiry!” The cop received no discipline. “It couldn’t be more on par with Jervis’ 2018 conduct—except it’s way worse,” he says.

In the “dick pick” incident, two of Middleton’s white colleagues, while in uniform, allegedly shared pictures of their penises with private citizens or in public forums, according to the lawsuit. Although the men received suspensions, members of the city council were told only that they had engaged in “inappropriate conduct.”

More troubling, the suit refers to an incident in which a white Lexington officer, James Dellacamera, pulled a gun on a woman he’d been seeing. Evidence produced in the case shows that during the wee hours of January 18, 2012, Dellacamera sent the woman, who is white, a series of angry texts, repeatedly calling her the n-word, “whore,” and “n—-r lover.” Fucking whore…die from dick, he wrote. You definitely [will]. Four hours later, he added: Did your monkey boyfriend come over?

Dellacamera also “referred to all the Black officers in the agency as n—–s,” Middleton testified in a sworn deposition. “That’s kind of a big deal to me.”

The city council, on the department’s recommendation, approved a six-month suspension for Dellacamera, who was still on the force when Middleton filed his lawsuit in 2021. But council members were never informed about the racial slurs, the lawsuit says. Middleton felt Dellacamera should have been fired—and said as much when the chief sat in on a departmental focus group of minority officers in which Middleton participated.

The lawsuit cites other instances of white cops receiving light discipline: One officer drove under the influence on multiple occasions, totaled his cruiser on one of them, managed to delay blood-alcohol testing for four hours, and got away with a two-month suspension. Another one dragged a suspect from a police cruiser, shoved him, and put his hands on the man’s throat—three weeks. Still another went to a wedding where she left her gun unattended for hours and got into a drunken brawl, striking a guest on the head and face and engaging in an altercation with the groom’s father—20 hours.

In Middleton’s view, the department downplayed the misbehavior of white officers, even as some of those officers went out of their way to play up his own lapses in judgment. When the local press reported on the claims of Middleton’s paramour, a white cop texted multiple photoshopped memes around the department, his lawsuit states. One showed Middleton on a bicycle pursuing a clearly creeped-out white woman. He perceived this as another racist taunt, but the brass did nothing about it.

The Black Lives Matter movement was born in 2013 after a jury acquitted George Zimmerman, the neighborhood watch volunteer who stalked and fatally shot unarmed Black teen Trayvon Martin in a Florida suburb. The verdict inspired protests and a social media hashtag—#BlackLivesMatter—that went mainstream the following summer, after Eric Garner and Michael Brown were killed by cops. As protests over racial injustice continued, Middleton felt a sense of kinship. “I’d seen it happen to me, how we’re treated differently,” he told me. “Black males, minorities, are guilty until proven innocent.” Watching the steady drip of police killings of Black and brown people in situations where deadly force appeared unjustified—and seeing their killers, mostly white men, walk away with a wrist slap—it “burns you up; it’s a boiling point,” Middleton says. “You see it from the inside, and then you start seeing it from the outside. It enrages you.”

The Floyd footage was the final straw. It “intensified” his feelings, Middleton testified at his hearing. “I felt for him. It was a culmination of everything that I had personally been through…It just bubbled over. I felt the same thing that people in society felt.” In short, he was coming to the realization that, when it came to confronting police brutality, being Black was more important to him than being a cop. On June 5, 2020, as BLM organizers prepared to protest in Lexington, he texted Williams, as he would several more times that summer, ftp. He then added: I guess Im working tonight… I hope yall give us the fucking business.. Hold nothing back!!!!! I will be fist up!!!

Williams and her daughter Gabby, then 17, were headed to her car after a BLM rally later that month when a swarm of police cruisers and bicycle cops descended on them. Gabby captured the arrest on her cellphone. Williams, her hands cuffed behind her back, looks at her daughter frantically. “Take my phone!” she implores—it’s in her back pocket.

“Let me get her phone!” Gabby called to the police, to no avail. The arresting officer would later testify that the police searched the phone for evidence against Williams, who was ultimately charged with five misdemeanors, including inciting a riot. (A jury acquitted her this past July of all charges but one: disorderly conduct, for which she paid a $200 fine.)

In the video, Gabby can be heard sobbing as officers take Williams to the ground. “I want my mama!” she shrieks. “Why y’all doing this?!” When an officer places a knee on Williams’ back, it’s a visceral trigger. She and other activists, she told me later, had recently performed an emotional “die-in” to commemorate the nine minutes that Chauvin’s knee rested on Floyd’s neck.

Racial justice activist Sarah Williams with three of her children.

Michael Blackshire

Once the department obtained a warrant to search Williams’ phone and discovered the texts, investigators began building their case against Middleton. An official complaint, filed two months after Williams’ arrest, accused him of releasing sensitive information without authorization and making disparaging comments about the department and its officers. Williams, “a known protester,” had used this information to publicly denounce Lexington officers and the department during the protests, according to an LPD memo, which put stress on the officers and “impacted their ability to maintain a professional demeanor.”

But unfounded rumors had made Middleton persona non grata well before the department even launched its official probe, according to Aguiar. During one interview, Officer Ryan Holland, whom Middleton named in his messages, was asked a leading question about how Middleton seemed to know so much about the intelligence BLM activists had on him and other cops. Holland laughed scornfully. “Because he’s their little snitch,” he said, adding, “I don’t trust him…he shouldn’t be a police officer.”

With a population of about 320,000, Lexington is small enough that police and their critics inevitably share social connections. Holland played drums in the high school band with Williams (who played alto sax) and her twin sister, April (trombone). Williams looks back fondly on her time in the ensemble, which regularly won state championships. “We all came together from different backgrounds to create something beautiful. We had a common goal.” But “now there is not a common goal,” she says. “They won’t recognize our humanity.”

Middleton felt alone at every step during his disciplinary hearing, which was initiated by Lexington’s Black chief. At these quasi–court proceedings, which happen only when an officer contests a disciplinary action sought by the department, the council members serve as jurors and Lexington’s mayor presides. (Middleton’s hearing, a council spokesperson told me, “is the only one we can recall in the last five years.”) Among the witnesses called by Keith Sparks, a local lawyer the police union paid to defend Middleton, was Williams, who likened Middleton’s treatment to a “metaphorical lynching.” The verdict was unanimous, however—even the council’s lone Black member voted against him. “Officer Middleton has been found guilty of violation of operational rules,” Mayor Linda Gorton read from a sheet of paper. “The discipline to be imposed upon Officer Middleton is as follows: termination.” Middleton filed an appeal, which the city rejected a few weeks later.

“While Officer Middleton’s actions may warrant some level of disciplinary action,” Michael Aldridge, the former executive director of the ACLU of Kentucky, proclaimed in a statement at the time, “it is particularly concerning he was more swiftly investigated and harshly punished for sharing non-critical information than officers who use excessive force against protesters or create the culture of racism and hostility Middleton reported to no avail.”

One thing a visitor may notice upon walking into Sam Aguiar’s law offices in Louisville, about an hour and a half from Lexington, is a raised fist carved into the woodwork. Aguiar—who, if he had bushy white eyebrows and an earring, would be a dead ringer for Mr. Clean—led the legal team representing the family of Breonna Taylor, whose killing by police resulted in a record settlement with the Louisville police department and, more recently, guilty verdicts in the federal civil rights case against some of the officers involved. Aguiar keeps a photo of Taylor on his office wall, along with photos of Floyd and Martin Luther King Jr. He got involved in the Lexington case after Middleton and his wife approached him. He dresses for our interview in an Adidas shirt, gym shorts, and sneakers. Aguiar likes things “very casual”—he even wore a T-shirt to one of the Taylor press conferences.

Although Middleton’s lawsuit was never a slam dunk, Aguiar was feeling optimistic prior to the recent court ruling. During discovery phase of the case, in which the department was compelled to hand over internal records and witnesses sit for depositions—Aguiar conducted nearly two dozen interviews. This and other evidence revealed, he says, that Middleton was vilified internally for showing solidarity with the Floyd protesters well before the police had evidence of misconduct. In fact, the chief’s office had looked into a rumor that Middleton had given protesters a roster containing fellow officers’ names, phone numbers, and addresses. “It never happened,” Aguiar says. But the inquiry file “showed there was a lot of internal Facebook chatter with a lot of derogatory language from cops about Jervis: ‘Fuck him’ this, and ‘He’s not worth a pile of carbon’ that.”

What’s interesting, Aguiar adds, is that Middleton was fired for dissemination of internal information—info that turned out to be pretty harmless—and disparagement. Yet commanding officers admitted in depositions that Middleton was far from the only Lexington cop to disparage fellow police: “They said, ‘This doesn’t even rise to an investigation. This is something we handle at the bureau level: You’re grown men; we’re gonna sit down and try to work this out,’” Aguiar says. And “it is unprecedented for talking shit about another officer to evolve into an investigative effort.”

His office also obtained a “treasure trove of historical allegations against Lexington officers, the investigation, the conclusion, the dispositions” which bolstered their case that white officers who said and did things far more egregious than Middleton was accused of, both on and off duty, were subjected to relatively light discipline, or none at all.

Also notable: The department’s standard disciplinary recommendation for an officer who disparages his peers is that the officer receive a reprimand for a first offense and a one-day suspension for a second offense. For a cop who doles out internal information, the recommendation for a first offense is a 30-day suspension. The LPD deviated from its own recommendations “in a gigantic fashion,” Aguiar said. “You know who had no idea? The fucking council!…The council was not ever presented with any sort of comparative cases or recommended discipline. So they had no basis for comparison.”

Potter, the criminologist, says that Middleton’s lawsuit, win or lose, will “shed light on systemic racism in Lexington.” Middleton has to show either that the department violated the Kentucky Civil Rights Act by creating a hostile work environment or that it engaged in disparate treatment by disciplining him more harshly than officers in “non-protected” classes accused of similar violations. “In essence,” the lawsuit reads, the decision to fire Middleton “sent a strong message to the department that the Blue Wall of Silence is not a fiction; an Officer had better not disclose Officer misconduct outside the police or he or she will no longer be permitted within the brotherhood.”

NYPD lieutenant Edwin Raymond can relate. He experienced firsthand the ostracism that comes with speaking out about racism in policing. “You hear what’s said behind your back,” he says. “I’m a traitor, I’m a rat, I don’t belong in policing. I’m an example of what happens when standards are lowered.”

He kept his job, though. Maybe it was safety in numbers. Raymond is part of the so-called NYPD 12—a group of officers engaged in a long-running racial discrimination suit against New York City. In 2013, they helped expose the profiling implicit in the department’s “stop-and-frisk” policy (at one point secretly recording a deputy inspector telling his troops to target “male Blacks, 14 to 21”). That case remains unresolved.

Raymond points to the “cult-like mentality” of law enforcement: “If you’re not down with that, you’re seen as the enemy, you’re seen as the problem.” He feels for Middleton. “The fact that he is not completely blinded by the blue and engaged in the tribalism that typically exists—that’s his real offense,” he says. “They just needed something to make it seem official and they got him on some technicality that was, to me, honestly, quite a stretch.”

Nationwide, the effort to turn Floyd’s killing into a catalyst for police reform met with resistance from the start. That summer, a handful of Chicago cops, some white, made the symbolic gesture of kneeling in the street to show support for the demonstrators’ cause. The president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police threatened to expel them from the union. Carmella Means, a 26-year veteran of the force, responded by posting to social media a photo of her kneeling in front of the union office holding a “Black Lives Matter” sign, fist raised. True to the president’s threat, the chapter suspended her.

Policing the protests was “absolutely brutal,” Raymond says. He fielded daily calls from Black colleagues who, like Middleton, were deeply frustrated and “saying they were going to quit, saying they didn’t like what happened to Mr. Floyd; they were at the protest they didn’t want to be at.” The protesters’ rage also took a toll. “People just assume you fall into the same category as these other stupid cops that are putting knees on necks and shooting people,” Philadelphia police officer Elizabeth Evans told Crime Report. As “a Black woman, it’s disheartening to hear that come from your own people, even though I understand 100 percent why they’re protesting and would protest with them.”

Even if Middleton prevails in his appeal, it would be hard to imagine him returning to law enforcement—asking for reinstatement, after all, is merely a legal prerequisite for recovering back pay. Even cops fired for excessive force and other serious violations of public trust often manage to find work with other departments, but that’s probably not an option for Middleton. Prospective employers may conclude, as those Lexington cops did, that he’s a troublemaker—a radical. He’s weighing his options. “Not sure, honestly,” he says, when I ask what’s next for him. But “I recently completed the LSAT and will be applying to law school.”

This story was supported by grants from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Los Angeles Press Club. Rowan Moore Gerety contributed reporting.