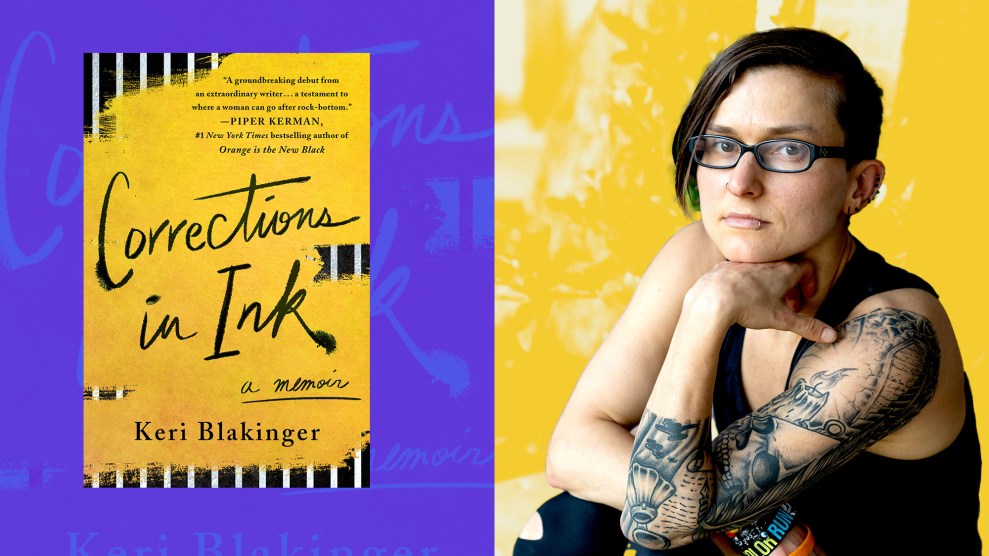

Mother Jones; Ilana Panich Linsman

Keri Blakinger, a reporter at the Los Angeles Times, hardly owns any furniture. She likes it that way, preferring to sleep on the floor rather than a cushioned mattress, and to keep her clothes permanently in suitcases. It’s not that she can’t afford a bed or dresser: Her career has taken off in the last several years. She was on the Houston Chronicle’s Pulitzer finalist team in 2018, and her reporting for the Washington Post helped win a National Magazine Award in 2020. But “belongings stress me out,” she told me recently, “because it was so ingrained in me: Everything you own is just something guards can take away.”

Blakinger’s new memoir, Corrections in Ink, tells the story of her 21-month incarceration in New York for a 2010 drug crime and her journey from prison to journalism; since landing her first reporting job, she’s focused on exposing the brutal conditions in other prisons and jails. To commemorate the paperback launch of her memoir this summer, she met me in San Francisco recently for a book event with Piper Kerman, whose memoir, Orange Is the New Black, inspired the hit Netflix show. The duo, who are friends, ranted about bad prison food, worse prison rules, and some of the little-known horrors of women’s lockups; the conversation was so thought-provoking we decided to share excerpts of it online.

Samantha Michaels: Both of you write in your books about how, soon after you got to prison or jail, you realized these facilities aren’t designed with women in mind. They’re more so built for men. Can you give some examples?

Keri Blakinger: When I was in New York, men and women both got five rolls of single-ply toilet paper a month. Clearly a man made that fucking rule—like, that’s absurd. Women would be using towels and magazines by the end of the month.

You also see it in a lot of other ways, like you could go to SHU [solitary confinement] for holding hands or hugging. These rules about contact were designed to deal with male social structures and male violence—women aren’t trying to hug each other to stab each other. And prison ends up shaming women for basic things. When I was in jail, if you were changing a tampon, the way the toilets and cells were set up, male guards could walk in on you and male inmates could walk by.

Piper Kerman: The vast majority of women who end up incarcerated are survivors of sexual violence, like 80-90 percent, or some other physical violence…The other wrinkle is that women are overwhelmingly single heads of household, so when you choose to incarcerate a woman, a mother, it has a seismic impact on the family and the community, and there’s nothing about the way the system is built that acknowledges that reality.

I want to ask more about prison conditions, but I think we can cover a broader territory if we do it in a lightning round: If you’re up for it, try to keep the answers to maybe 20 seconds?

KB: That sounds like TikTok material. [Audience laughs.]

Let’s start with prison food. What was the grossest meal you saw served?

KB: Cereal with a cockroach crawling out. [Audience groans.]

PK: The most consistently bad was the roast beef. In the federal system—I was incarcerated from 2004 to 2005—there were foodstuffs in the kitchen that were labeled “Desert Storm.” [Audience laughs.] That roast beef was always green.

People in prison often cook their own food, too, like with the microwave. What was the weirdest or best prison recipe you made or ate?

KB: I’ve always been terrible at cooking—my strategy was to have a hot girlfriend do the cooking. But we did eat apples dipped in sweetened condensed milk. You could get canned food sent into New York prisons back then. Q-tips were banned, but cans with their sharp edges were allowed.

PK: What are you gonna do with a Q-tip?

KB: I don’t fucking know.

PK: I knew how to make one recipe: the prison cheesecake recipe in my book. I stand by it. But there were ways of making chilaquiles with contraband onions, Goya seasoning from the commissary, and corn chips that had been dampened. Mix up all the ingredients, put them back into the plastic bag, duct tape it shut, and cook it in the microwave, which I’m sure is a cancer risk, but it was delicious.

KB: Have you seen how they make ovens in Texas prisons?

PK: What’s the heating element?

KB: A hair dryer. They take a paper bag, cut a hole in it the size of a hair dryer. They put the metal part of the chip bag on the bottom, they put the food inside, and then they blow-dry it, like a fryer.

PK: I mean, this is sort of to the point, though: Having the privilege of a microwave is something that can be taken away. Depending on what prison staff was on duty in your unit, the threat of taking away the microwaves was constant. Any of these amenities that make life more bearable are things that can be used as tools of control.

Speaking of things being taken away, what was the weirdest contraband item you kept or heard of?

KB: My cellie got in trouble for keeping her hair in an envelope.

Cut hair?

KB: It was falling out. She was trying to prove it to medical, and they gave her a ticket for unauthorized possession of an item. She went to keeplock over that. Which is funny, because she actually got drugs and they didn’t catch her for those.

What was the dumbest prison rule you can remember?

PK: “No touching!” You’re not supposed to touch anybody.

KB: This wasn’t even while I was in: The one that New York rescinded yesterday—that was fucked-up shit. New York banned prisoners from doing journalism. And then there was an outcry and they reversed it. That’s gotta be one of the dumbest rules.

PK: Definitely. And they’re constantly trying to ban books. That’s one of the things that gets the most outcry from the outside community. What’s interesting to me is the psychology of what we feel outraged about that transpires in the prison system.

KB: One thing I’ve noticed in covering book bans is that people don’t care that books are systemically banned, but they will get energized around a specific title being banned.

PK: That brings us into the inherent question around memoir: the idea that an individual story can focus our attention and emotions in a way that broader questions sometimes fail to.

KB: Yeah, for stories to land, you need the specific example. If I write about the LA jail lawsuits, for instance, that story will not do well if I’m just like, “The judge said this, things are bad, here’s the data.” But if I have a photo of a guy with an inch-deep gash in his head, that will do well, or if I have a specific anecdote, like they’re not giving them toilet paper so they’re wiping their asses with orange juice cartons—that is something people can wrap their heads around.

Keri, your book has been banned in some prisons. Why?

KB: Stupid reasons. There’s one chapter where my friend created a fake pet chicken. If she got caught making a petition to try to get pay increased, she was going to say she was looking for her chicken that was lost, and she’d pull these chicken bones out of her pocket, and [the officers] were gonna be like, “Oh, she’s crazy. She can’t go to SHU.” That was her plan and I described that, and [the censors] said it was teaching people how to fake a mental health crisis. I mean, it’s really arbitrary. It depends who’s in the mail room.

What was the best book to read prison?

KB: Long books, because there were limits on how many you could have in your cell at one time. Infinite Jest is good for prison reading. [Kerman groans. Audience laughs.] So are Norton anthologies. I just wanted as many pages as possible. Like when I was in solitary and I could only have one book, Infinite Jest.

PK: Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex. I haven’t read it recently; I’m not sure if it aged well as our ideas about gender continue to evolve. But I enjoyed that, and a lot of other people who I was incarcerated with enjoyed it. And then The Glass Castle, a wildly bestselling memoir [by Jeannette Walls]. I read that close to the end of my incarceration. Reflecting on her incredibly challenging childhood made me feel like, “Okay, I’ll get through this.”

Last one: What’s part of your prison routine that stays with you today?

PK: I have an embarrassing affinity for uniforms: not for people wearing them, but for me, like in my day-to-day life.

KB: I sleep on the floor, and I don’t really own furniture. I’m way less stressed out when I don’t own things. And also, I got really used to sleeping on a hard bunk. So I actually like sleeping on the floor, which is not great for dating. [Audience laughs.]

Let’s end the lightning round. You both write about privilege, how you had advantages in prison because you’re white, middle class, and educated at elite colleges. How soon into your incarceration did you become aware of those privileges? And when it came time to write, how did you think about spotlighting your experience when there are so many other stories by less privileged people that aren’t heard by such a big audience?

KB: For me, it was a growing realization over time. I don’t think I fully appreciated the ripple effects until I got out in 2012 or 2013, sort of the cusp of when people were starting to talk about white privilege a lot more.

PK: For me, it was day one. Prison staff were literally like, “What are you doing here?” And very quickly, there were so many women I met who were doing exponentially longer sentences than I was, even though their crimes of conviction were not substantially different.

KB: Part of why this was not as apparent to me when I got arrested was because the county I was in was so overwhelmingly white. There was no woman of color the entire 10 months I was in county [jail]. And I ended up doing the most time out of anyone I was there with, so it wasn’t apparent until I saw the much larger pool of who’s in prison.

But you do reflect in your book on the privileges you had coming out of prison, and how, easing back into life, there were certain things that were easier for you.

KB: Yeah, I don’t want people to hear my story and have the takeaway be like, “Well, why isn’t everyone doing that well after prison?” I wanted to explain some of the systemic barriers that prevent more people from having these outcomes.

Tell us more about the process of writing the book.

KB: I’ve written enough essays and talked about my prison experience, so it wasn’t emotionally that difficult; it was much harder after the book came out. I was getting asked rude and absurd questions about it, about myself. Having to answer these in interview after interview was draining.

PK: I started writing in 2007, and I was clear I wanted to write a book that would reach people who were unlikely to read about prison. I wanted a wider array of people to think about mass incarceration, having the biggest prison population in human history. That’s heavy stuff, but I also wanted to reflect the incredible vitality, creativity, intelligence, and persistence of the women I was incarcerated with, and all the things that were amazing about them. The book is not comic—it differs from the show in a variety of ways—but it was not intended to be a book that left you feeling downtrodden or giving up.

In recent years, there’s been progress convincing more people that mass incarceration is bad and prison conditions are inhumane. Do you think that progress is being rolled back now, given the rising concerns about crime during the pandemic?

KB: The pandemic made a lot of people wrongly think progress had been made—because it resulted in lowering [prison] populations. But in a lot of jurisdictions, people have no idea how bad things continue to be. I’ve been deeply depressed going through the LA Times archives over the past 150 years and seeing the extent to which nothing changed. Like, things that are filed in lawsuits currently against the jails are identical to things that the LA Times was writing about in editorials in the 1910s: overcrowding, people sleeping on floors. As far as I can tell, the only thing that has changed since the 1850s is that at one time, people in LA jails were not allowed to have toothbrushes, towels, or blankets.

PK: The pandemic and our failure to enact mass releases of hundreds of thousands of people who unquestionably could be safely returned to the community in the midst of a public health crisis—that was sobering for me. Like, this can’t be reformed, and we need to do something different. What has changed a lot in the last 15 years is the rhetoric around mass incarceration, the public discussion. But Keri is right that when the rubber meets the road, we are still sending people, vastly disproportionately people of color, into dire and desperate situations, often for extraordinarily low-level offenses. That has not changed.

Let’s open it up to the audience. Any questions?

Audience member: What about gangs in women’s prisons? Is that a thing?

PK: Games? Like “Magic: The Gathering”?

Audience member: Gangs.

PK: Gangs! So “Magic: The Gathering,” by the way [audience laughs]: When I got to this men’s prison in Ohio, where I worked for four years teaching writing, several guys in the class were really into “Magic: The Gathering.”

KB: They play “Dungeons & Dragons” on death row. They make the spinners.

PK: There was very little gang presence where I was incarcerated. In contrast, in men’s facilities, there can be a lot of gang activity. They run gambling rackets, drug rackets, contraband rackets, protection rackets. It’s not that women don’t run rackets, but if I had to make a sweeping statement: Incarcerated men tend to have more contact with the outside world than incarcerated women.

KB: Part of this is because of the gangs, though: They create a structure for getting certain things smuggled in, contraband cell phones. That also means we have a better eye into what happens in men’s prisons: I have so many videos and photos from men’s prisons, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything on contraband phone from a women’s prison.

PK: It’s rare. Also, women serve as a lifeline for incarcerated men. They have their mothers, sisters, girlfriends, wives. Incarcerated women tend to have far fewer people on the outside looking out for them. When you go into a women’s prison or jail, it seems profoundly cut off from the outside world in a way that is different, to me, than men’s.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.